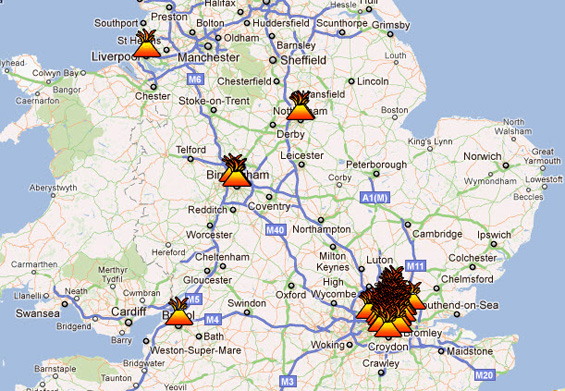

What causes urban riots?

Posted: August 10, 2011 | Author: Alan Davies | Filed under: Social and community | Tags: Brendan O'Neill, Denise DiPasquale, Edward Glaeser, London, Los Angeles, Miami, riots, UK, Watts | 29 CommentsBritish leftie, Brendan O’Neill, takes an unsympathetic view of the UK rioters in this article, London’s burning: a mob made by the welfare state. He dismisses popular explanations like racism, characterising the rioters as “welfare-state mobs” who are destroying their own communities.

Painting these riots as some kind of action replay of historic political streetfights against capitalist bosses or racist cops might allow armchair radicals to get their intellectual rocks off, as they lift their noses from dusty tomes about the Levellers or the Suffragettes and fantasise that a political upheaval of equal worth is now occurring outside their windows. But such shameless projection misses what is new and peculiar and deeply worrying about these riots. The political context is not the cuts agenda or racist policing – it is the welfare state, which, it is now clear, has nurtured a new generation that has absolutely no sense of community spirit or social solidarity.

Harvard economist Edward Glaeser (author of my last book giveaway, Triumph of the City) has a long interest in the causes and consequences of urban violence. In this paper, The Los Angeles riot and the politics of unrest, Professor Glaeser and colleague Denise DiPasquale examined the tragic history of post-war riots in the US (H/T Christian Dimmer, @remmid).

The LA riot of 1992 – sparked by the police beating of Rodney King – lasted three days and resulted in 52 deaths, 2,499 injuries, 6,559 arrests, 377 buildings completely destroyed and 222 seriously damaged. Seventeen people died and 400 were arrested in the two-day Miami riot in 1980. In 1965, a six-day riot in Watts resulted in 34 deaths, 1,032 injuries and 800 buildings damaged or destroyed.

DiPasquale and Glaeser examined the causes of rioting using international data, evidence from the race riots of the 1960s in the US, and Census data on Los Angeles, 1990. Their empirical results suggest high levels of ethnic diversity and unemployment among young black men, combined with the “sheer size” of LA, all help to explain the 1992 riot.

However they found little support for the notion that poverty is a major determinant of which cities riot. Nor did they find a connection between high levels of migration – a proxy for social capital – and rioting. They conclude that rioting is driven to some extent by the probability and size of punishment. An increase in the probability of arrest, they say, lessens the probability of a riot and its size. Individual costs and benefits matter.

We find some support for the notions that the opportunity cost of time and the potential cost of punishment influence the incidence and intensity of riots. Beyond these individual costs and benefits, community structure matters. In our results, ethnic diversity seems a significant determinant of rioting, while we find little evidence that poverty in the community matters.

Brendan O’Neill says the intrusion of the welfare state in the UK over the past 30 years “has pushed aside older ideals of self-reliance and community spirit”. The most striking thing about the rioters, he says, is how little they seem to care for their own communities – the violence is not political, but merely criminal: Read the rest of this entry »