Are driverless cars a game changer?

Posted: November 30, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: autonomous vehicles, driverless cars, emissions, Public transport 21 CommentsA common observation by many historians I’ve read goes like this: “they failed to understand just how important such-and-such was going to be in the future”. In many cases, “such-and-such” is a decisive technology that went unrecognized until it ended up completely changing the game.

Well, I think one technology that’s being grossly under-estimated today is Driverless Cars (DCs). If they could deliver fully on their promise, they’d have an enormous impact and bring a triple bottom line improvement to our cities – more efficient, more equitable and better for the environment.

There’s plenty of commentary around on driverless cars and I wrote at length on their potential as recently as May 31, in Are driverless cars coming? In that piece, I discussed the current state of the technology and some of the formidable technical, social and legal obstacles to a driverless car fleet.

However as we know from the history of electricity, public sanitation, the car, the computer, inoculation, the pill and many other innovations, it’s very hard to deny an irresistible idea. Given enough time – say the 30 year horizon typical of current planning strategies – it’s possible the sheer weight of benefits DCs promise our cities will provide the motive force to overcome these obstacles.

The key potential benefits are:

- Expansion in the effective capacity of the road system – at least double and perhaps eight times as much, with consequent savings in infrastructure provision

- Time savings from faster journeys – technology can manage vehicle interactions and speeds more efficiently than human drivers (although there might be a trade-off with capacity here)

- Almost complete elimination of serious injuries and fatalities associated with accidents

- More productive use of in-vehicle journey time compared to conventional cars

- Greater mobility for those who cannot drive e.g. the unlicensed, disabled, drunk

These are potentially enormous private and social benefits. In addition, the warrant for owning a private vehicle would be greatly reduced in a world of DCs. If a total or substantial shift to DC-sharing were achieved, the size of the urban car fleet would be reduced by an order of magnitude. There would be many benefits:

- Lower environmental impact because many fewer vehicles would need to be manufactured

- Less public and private space devoted to parking – this could greatly enhance the quality of public spaces and even residential streetscapes

- Better matching of vehicle type to need, resulting in lower resource and environmental costs e.g. many DCs could be single seaters

- Lower cost of travel due to eliminating need for vehicle ownership and removing the “status” component

- Reduced noise, pollution, emissions and energy consumption by virtue of having a more efficient “standard” set of vehicles

- The opportunity to rationalise the way travel is paid for by introducing a new pricing ‘paradigm’ – all standing and variable costs, including externalities, could be incorporated in a distance-related tariff (this isn’t intrinsic to DCs, but the changeover to a new paradigm provides the opportunity)

There are other potential strategic benefits too. Driverless cars could greatly reduce (though not eliminate) the need for public transport. This would offer a number of potential advantages:

- Faster, safer and more private travel for those who currently use public transport – many travellers would enjoy very significant time savings

- A higher proportion of the total cost of providing transport in the city could be borne directly by DC users rather than, as at present, by taxpayers

DCs aren’t just a replacement for the car, they’re a potential game-changer for the entire urban transport task. Read the rest of this entry »

Is The Age providing fair comment on transport issues?

Posted: November 29, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: Department of Transport, East West Tunnel, Eastern Freeway, Eddington Report, Kenneth Davidson, Melbourne Metro, Northern Central City Corridor strategy, Regional Rail Link, Sir Rod Eddington 6 CommentsI take an agnostic view of freeway proposals – I don’t assume apriori that they’re all bad or all good. I prefer to look at the evidence first before deciding if a proposal has merit or is a poor idea. But it seems there are some who will overlook evidence to the contrary if it undermines their ideological view.

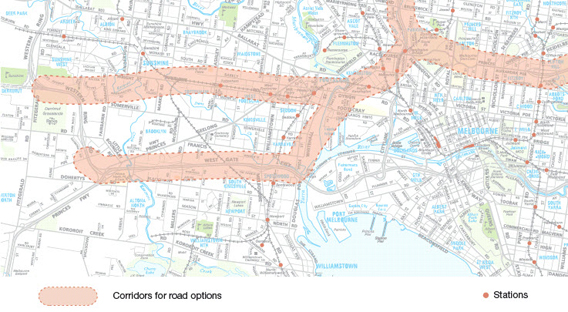

Like Kenneth Davidson in his column in The Age on Monday, Why the east-west road tunnel is a stinker, I have some misgivings about the tunnel proposed to connect Melbourne’s Eastern Freeway with the Western Ring Road. The Victorian Government has just submitted a proposal to Infrastructure Australia, seeking funding to develop the tunnel idea further.

My key concern is the anaemic benefit-cost ratio. But Mr Davidson, who’s a senior columnist at The Age, goes further. He reckons the proposed tunnel recommended in 2008 in the Eddington Report is a “stinker” and a “confidence trick”.

That’s because an earlier study undertaken for the Bracks government in 2004, the Northern Central City Corridor strategy (NCCC), found most of the traffic coming off the Eastern Freeway heads into central Melbourne. It found only 15% is bound for the northern or western suburbs. “In other words”, Mr Davidson says:

the public justification for the east-west link – that it would take traffic away from the central business district – was a confidence trick……The first question (Eddington) should have asked was where did the 2004 study go wrong.

I don’t think anyone disputes the NCCC study was negative about the case for the tunnel. Nor is Mr Davidson the first to raise this objection. The “gotcha” Mr Davidson seizes on with such alacrity is that Sir Rod Eddington apparently ignored the NCCC study’s key finding.

But it seems it’s Mr Davidson who’s doing the ignoring. The Eddington Report actually does consider the NCCC study. Moreover it deals with it in a way that is prominent and impossible to miss by anyone with their eyes open (read it – Chapter 5, page 129).

The Report argues it’s a myth that nearly all Eastern Freeway traffic is destined for the inner city. It says the NCCC produced diagrams that present “a distorted view of traffic distribution (and further NCCC modelling for a future link would have identified and addressed this issue)”.

In a section titled, ‘Myth 2: nearly all the Eastern Freeway traffic is destined for the inner city’, It argues the NCCC study didn’t look beyond the capacity of existing roads or the ultimate destination of traffic once it left the NCCC study area.

First, given the roads in question, the traffic distribution (identified in the NCCC study) is not surprising: at the end of the freeway, there are ten freeway standard traffic lanes (five each way). By the time traffic reaches Macarthur Avenue in Royal Park, the corresponding ‘connection’ is a two-lane road (one lane each way). The traffic distribution is as much a function of the roads available, which progressively reduce in capacity towards the west, as it is a reflection of the demand for a particular direction of travel.

Secondly, when the (Eddington) Study Team analysed how traffic from the Eastern Freeway is distributed (with the analysis closely matching the NCCC distribution), it revealed that around 40 per cent of the daily traffic from the freeway travels beyond the central city area – to the south and the west. That is the case with the current network: in the future, EastLink will add a new dimension.

The Eddington Report also argues (page 137) the NCCC study focussed on Eastern Freeway traffic and didn’t fully consider traffic using adjacent streets instead. Moreover, it didn’t recommend against the tunnel because insufficient vehicles would use it, but rather because the high cost of construction yielded an inadequate benefit-cost ratio. Read the rest of this entry »

Are public transport trips longer (than car trips)?

Posted: November 28, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: car, distance, Public transport, trip, VISTA 6 CommentsI’ve frequently mentioned that trips by public transport in Melbourne are longer on average than those by car. The exhibit above illustrates that difference using data from the Department of Transport’s VISTA data base.

It shows the length of non-work trips in Melbourne by private vehicles versus public transport. For all practical purposes, it’s cars on the one hand (in red), versus trains, trams and buses combined on the other (in blue).

A ‘trip’ refers to travel between main activities. Where multiple modes are used on one trip a single ‘main mode’ is defined. For example, if a person drives from home to the station, catches a train to the city, and walks to their destination, their mode for the trip is the train.

It’s important to get these figures in perspective from the outset. There are almost fourteen times as many non-work trips made by car as are made by public transport. This reflects the dominance of private transport in Melbourne.

It’s evident from the exhibit non-workcar trips are substantially shorter – just compare the two fitted curves. In fact 56% are less than 5 km, whereas the corresponding figure for public transport is 27%. At the other end of the scale, 5% of non-work car trips are longer than 30 km, compared to 9% of public transport trips.

Work trips (i.e. commutes) tend to be longer than non-work trips in the case of both private and public transport, but again public transport trips are longer on average. For example, 40% of commutes by public transport exceed 20 km. The corresponding proportion for car commutes is much lower, at 27%.

I’ve shown non-work trips in the exhibit because they account for around four fifths of all trips (defined as per above). They are not as dominant in the case of public transport, but still comprise two thirds of all trips by trains, trams and buses.

Trains are the key reason public transport trips are so much longer – people travel considerably further on metropolitan trains on average than they do on buses and trams. I don’t have data to hand that separates out trains (I hope to get my hands on it shortly), but the difference between cars and trains would be much more dramatic.

It’s not that the train out-competes the car for long trips. In fact many more people still prefer to use the car for long trips than take any form of public transport. For example, while 7% of non-work car trips are over 25 km compared to 14% of public transport trips (they’re virtually all train), the car trips number 534,000 per day. The comparable number of trips made by public transport passengers is just 80,000.

Rather, people who choose to travel by train are more inclined to use it for longer distances, on average, than car travellers. I’d say that’s largely because Melbourne’s train system is designed to transport people across long distances – primarily from the suburbs to the city centre.

Cars are flexible and in non-congested conditions can get travellers to a range of dispersed destinations, both near and far. Melbourne’s train system on the other hand is relatively inflexible by comparison. It essentially leads to one destination. Read the rest of this entry »

Are these really the most (and least) liveable suburbs in Melbourne?

Posted: November 27, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: Hallam, index, Liveability, Our Liveable City, South Yarra, suburb, The Age, Tract 10 CommentsI never read those glossy magazine inserts in The Age (who does?) but on Friday I made an exception for The Melbourne Magazine because it promised to tell me “the most liveable suburb in the world’s most liveable city”.

The Age’s Our liveable city project ranks the “liveability” of 314 suburbs from top to bottom and claims to reveal “Melbourne’s best suburbs, the ones improving the most, and where you should buy your next home”.

Liveability is defined initially as “the general quality of a place that makes it pleasant or agreeable for people to reside in”. Fortunately, someone saw that was a tautology and wouldn’t be of any practical help. So liveability is subsequently defined by 13 measurable criteria.

These cover topography, traffic, crime, cultural facilities and parks, as well as proximity to a range of amenities – the CBD, beaches, public transport, schools, restaurants and shops. Scores out of five on each criterion are added to give an overall summary score for each suburb. Each suburb is subsequently ranked from 1 to 314 on an Index of Liveability.

Unsurprisingly with this sort of exercise, there was a lot of criticism from readers, with many pointing to apparent anomalies in the rankings. One said, “once I saw Footscray was rated higher than Middle Park I stopped reading”.

Disagreement is inevitable. People are different and so it’s hard to get consensus on just what does, or doesn’t, make a place liveable. That shouldn’t be surprising – an elderly couple, for example, is likely to have a very different definition of liveability to that of a young single. Throw in further differences, say in education, income or ethnicity, and it gets much more complex.

There is a much more straightforward and reliable way of establishing the relative liveability of suburbs. That simply involves measuring what people are prepared to pay to live in them i.e. property prices. It doesn’t require complex measures and weights (not that The Age bothered with the latter). In fact it sidesteps entirely the hardest and most intractable question of all – defining apriori just what liveability is.

Moreover, it provides a clear ranking and allows us to measure the size of the difference between suburbs. And it’s based on the actual decisions of hundreds of thousands of householders. Knowing that the average property value in South Yarra is three and a half times higher than in Hallam is a much more useful and valuable piece of information about the relative merits of the two suburbs than knowing one ranks 350 places ahead of the other on the Index of Liveability.

There’re distortions in the market so property values aren’t a perfect representation of the relative liveability of Melbourne’s suburbs. I would argue however that this approach involves infinitely fewer compromises than the methodology used by The Age. Of course it wouldn’t make a very interesting story when there’s the option available to the newspaper of bringing some “science” to the issue.

That’s not to say exercises like the Index of Liveability don’t have value. They can be useful to establish just why residents think one suburb is more liveable than another. Knowing why properties average $1,300,000 in South Yarra and $369,000 in Hallam would be very important information for policy-makers.

Interpreted this way, I think The Age’s attempt is actually better than many of the commenters are prepared to concede (even though I’m annoyed that very little information about the methodology is disclosed). You can argue the toss at the margin – for example, I suspect proximity to schools only matters in the case of certain institutions – but by and large the criteria are a reasonable compromise. Read the rest of this entry »

What does ‘random’ look like?

Posted: November 24, 2011 Filed under: Miscellaneous | Tags: cognitive illusion, Ed Purcell, gambler's fallacy, London Blitz, Poisson, statistics, Steven Jay Gould, Steven Pinker, The Better Angles of our Nature, Thomas Pynchon, Waitomo 8 CommentsThe exhibit shows two seemingly similar patterns – but one of them is random and one isn’t. Can you tell which is which? More in a moment.

I’ve taken these plots from Steven Pinker’s new book, The better angels of our nature: why violence has declined. It’s in a Chapter titled The statistics of deadly quarrels where he discusses the statistical patterning of wars and takes a small detour into “a paradox of utility”, specifically our tendency to see randomness as regularity with little clustering.

This cognitive illusion has relevance to all disciplines but is of particular interest to anyone interested in spatial issues, as a couple of these examples show.

Professor Pinker, who’s a psychologist at Harvard, cites the example of the London blitz, when Londoners noticed a few sections of the city were hit by German V-2 rockets many times, while other parts were not hit at all:

They were convinced that the rockets were targeting particular kinds of neighborhoods. But when statisticians divided a map of London into small squares and counted the bomb strikes, they found that the strikes followed the distribution of a Poisson process—the bombs, in other words, were falling at random. The episode is depicted in Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 novel Gravity’s Rainbow, in which statistician Roger Mexico has correctly predicted the distribution of bomb strikes, though not their exact locations. Mexico has to deny that he is a psychic and fend off desperate demands for advice on where to hide

Another example is The Gambler’s Fallacy – the belief that after a long run of (say) heads, the next toss will be tails:

Tversky and Kahneman showed that people think that genuine sequences of coin flips (like TTHHTHTTTT) are fixed, because they have more long runs of heads or of tails than their intuitions allow, and they think that sequences that were jiggered to avoid long runs (like HTHTTHTHHT) are fair

The exhibit above shows a simulated plot of the stars on the left. On the right it shows the pattern made by glow worms on the ceiling of the famous Waitomo caves, New Zealand. The stars show constellation-like forms but the virtual planetarium produced by the glow worms is relatively uniform.

That’s because glow worms are gluttonous and inclined to eat anything that comes within snatching distance, so they keep their distance from each other and end up relatively evenly spaced i.e. non-randomly. Says Pinker:

The one on the left, with the clumps, strands, voids, and filaments (and perhaps, depending on your obsessions, animals, nudes, or Virgin Marys) is the array that was plotted at random, like stars. The one on the right, which seems to be haphazard, is the array whose positions were nudged apart, like glowworms

Thus random events will occur in clusters, because “it would take a non-random process to space them out. The human mind has great difficulty appreciating this law of probability”. Read the rest of this entry »

Could major housing developments be outside activity centres?

Posted: November 23, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: activity centre, infill housing, medium density, retrofit 16 Comments We need to start thinking about new ways of increasing housing supply in the established suburbs. As I’ve noted a number of times now, activity centres aren’t delivering much and infill housing, though it’s putting in a sterling effort, is probably at full stretch. These strategies are still important, but additional sources of supply are needed.

We need to start thinking about new ways of increasing housing supply in the established suburbs. As I’ve noted a number of times now, activity centres aren’t delivering much and infill housing, though it’s putting in a sterling effort, is probably at full stretch. These strategies are still important, but additional sources of supply are needed.

Much of the current thinking confines major developments to a narrow range of locations, primarily activity centres and major transport corridors where key infrastructure, particularly rail lines, already exists. Many have argued these locations have the potential to accommodate enough apartments to house all of Melbourne’s projected growth for decades to come. I don’t doubt they could in theory, but in reality they’re not doing enough.

I think there are lessons we can learn from the study of infill housing I discussed last time. One is the decisive importance of land – developers working at all scales need to be able to easily acquire or assemble sites that are of an appropriate size and aren’t encumbered by high-value improvements.

Developers don’t want to be rejected or delayed by unhappy neighbours or sent packing by councils that impose restrictive limits and conditions on development. And they need to offer housing types that are attractive to the market in that locality – not everyone who’d be inclined to live in the middle ring suburbs would want to live in an apartment.

I think there’s another option worth investigating that addresses many of these concerns. Although it’s just an idea at the moment, it involves a reverse strategy – encouraging residential and commercial development in areas that usually have poor infrastructure, but large sites and compliant neighbours. Rather than require infrastructure to be in place first, it involves retrofitting infrastructure like public transport in order to create new living areas.

It relies on the existence of sites in the suburbs which are large, in single or limited ownership, have few neighbours, and are either undeveloped or have relatively low-value improvements such as warehouses. Some sites that meet these criteria are attached to large public sector organisations like tertiary institutions and utilities, but are surplus to requirements.

As an example, I’m familiar with a tertiary institution in an Australian capital city that’s located within 20 km of the CBD and has more than 100 ha of surplus developable land (that’s five times the size of Melbourne’s E-Gate). It is in a single ownership and already has the extensive infrastructure and services required to serve a student population and workforce of many thousands.

It’s in an attractive environment and could potentially be redeveloped as a major regional activity centre at relatively high densities. It isn’t near a train line, but is well-connected by buses to the rail network with the potential to add more to suit the needs of a very large permanent resident population. I’m aware professionally of some opportunities in Melbourne that are consistent with this example.

However most of the prospective sites are likely to be used at present for storage, distribution and manufacturing activities. They’re not brownfields sites though, because they’re not disused. The idea is that rezoning would provide owners with an incentive to redevelop their properties for intensive residential and commercial uses.

The extended area running through Clayton/Monash/Glen Waverley is a possible candidate in Melbourne. It has a number of large industrial sites that could potentially be redeveloped given an appropriate inducement. This region is particularly important because it already has the largest concentration of jobs in suburban Melbourne (albeit at relatively low density compared to the CBD) and is a prime candidate for development as a Central Activities Area.

While it isn’t well-served by rail, it could potentially be retrofitted as part of the proposed Rowville rail project. More plausibly, it could be serviced at a lower up-front cost by an expanded bus rapid transit system similar to that now connecting Monash University with Glen Huntley Huntingdale station.

The overall idea of retrofitting relies on the sheer size and intensity of projects to provide the incentive for redevelopment and to justify investment in infrastructure. The scale of projects would also be a key way of differentiating developments from neighbouring uses, some of which may retain their non-residential character, at least in the short term. Read the rest of this entry »

Can Melbourne depend on infill housing?

Posted: November 22, 2011 Filed under: Housing, Planning | Tags: activity centre, City of Monash, Housing, infill, Jim Petersen, medium density, Monash University, Rail station, Shobit Chandra, Thu Phan 13 Comments

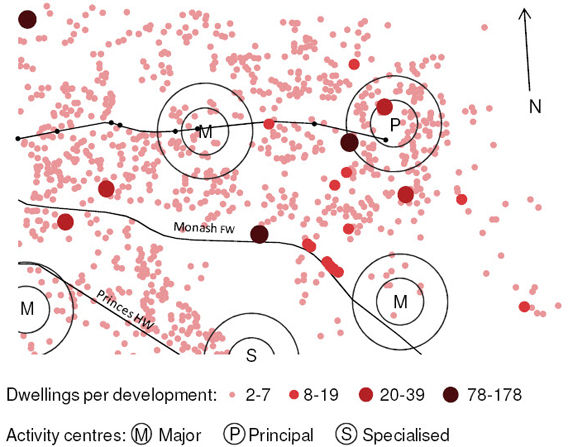

Geography of infill developments in City of Monash, 2000-2006 (source: Phan et al, 2008 - graphic via Grattan Institute)

We know that the inability to increase significantly the supply of dwellings within established suburbs is a key failing of strategic planning in Melbourne. Simply put, there’s not enough housing to make established suburbs affordable for all the people who would like to live in a relatively accessible location.

We also know that activity centres aren’t pulling their weight in the task of increasing supply (see here and here) and that the burden of supply is instead falling on small-scale infill development, much of it dual occupancy projects. So it’s worth looking further at the nature of infill housing.

A study by Monash University’s Thu Phan, Jim Peterson and Shobhit Chandra , Urban infill: the extent and implications in the City of Monash, examined new developments in the municipality over the period 2000-06. They defined infill primarily as projects where two or more new dwellings were constructed on sites formerly occupied by detached houses. A total of 1,483 projects were identified, ranging in size from two dwellings to 178.

The study revealed a number of interesting aspects about this middle suburban municipality.

First, it found new dwelling supply is dominated by small projects. One project built more than 178 dwellings and three built between 40-77 dwellings, however 98% of projects involve just 2-7 seven dwellings (and we can be pretty confident they’re heavily weighted toward the smaller end).

Second, projects are dispersed, not concentrated. As shown in the exhibit, proximity to major trip generators is uncorrelated with location of projects. Just 5% are within 400 metres of a Principal, Major or Specialised activity centre, and only 10% are within 400 metres of a rail station. Moreover, the authors found projects located within 400 metres of an activity centre are smaller on average than those in more distant locations.

Third, developers tend to be opportunistic rather than strategic – they wait for properties to be offered for sale and assess each one on its potential for redevelopment. Thus the geography of infill development is shaped largely by what comes on the market rather than by any sort of deterministic planning policy.

Fourth, the size of lots and the age of the existing house is a more important influence on the location of infill development than proximity to an activity centre or rail station. The average infill site is relatively large (700 to 900 sq m) and the majority of existing dwellings are relatively old i.e. built between 1945 and 1965. Lot sizes close to rail stations are smaller – and hence less amenable to redevelopment – than those further away, probably reflecting the different periods of development.

Thus not only are activity centres failing to expand housing supply in accordance with the precepts of Melbourne 2030, but the great bulk of new housing being built in Monash isn’t located close to activity centres but rather is dispersed (relatively uniformly too judging by the exhibit i.e. non-randomly).The dispersed pattern will worry some, but I don’t see it as a big issue. Read the rest of this entry »

What’s happened to the idea of the compact city?

Posted: November 21, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: Activity centres, compact development, DPCD, Housing Development Data 2004-2008, Melbourne 2030, Melbourne @ 5 Million, smart growth, urban consolidation 3 CommentsPending completion of the Government’s new urban strategy for Melbourne, the two major strategic planning documents that jointly guide the metropolitan area’s development – Melbourne 2030 and Melbourne @ 5 Million – are rich with rhetoric about the importance of directing development to established suburbs rather than the periphery. They also emphasise the desirability of concentrating that development around activity centres instead of dispersing it throughout the existing suburbs.

In a show of great political courage, Melbourne 2030 sought to limit the share of Melbourne’s population growth in peripheral Greenfield developments to just 38%. Virtually all the rest would be located within the established suburbs, of which 40% would be concentrated in activity centres.

However the supplementary strategy released six years later in 2008, Melbourne @ 5 Million, relaxed the target considerably. It was clever – it slackened the numerical target to 47% while simultaneously narrowing its geographical ambit to just the six Growth Area municipalities. These six cover an area much smaller than that implied by the term ‘greenfield’ used in Melbourne 2030.

This statistical report prepared by the Department of Planning and Community Development (DPCD), Housing Development Data 2004-2008, reveals that the new Melbourne @ 5 Million target wasn’t very demanding. It merely echoed the way the market had behaved over the preceding four years.

Over 2004-08, the Growth Area municipalities accounted for 44% of net new dwelling construction (after subtracting demolitions). Once the larger average household size of outer suburban households is taken into account, this is much the same as Melbourne @ 5 Million’s 47% population “target”. Rather than seek to change the market as its rhetoric suggests, Melbourne @ 5 Million was essentially business as usual.

In any event limiting the target to Growth Areas could be construed as misleading. They are not the same as the outer suburbs. There was considerable growth in other peripheral municipalities over 2004-08 e.g. Frankston, Nillumbik, Mornington Peninsula and Yarra Ranges. When they are added to the Growth Area municipalities, the outer suburbs accounted for 54% of all new dwelling construction in the metropolitan area over 2004-08. In terms of the share of population growth, the number would be somewhat higher.

So Melbourne @ 5 Million essentially had no real ambition to drive significantly higher housing supply in the established suburbs. Despite what the text sought to imply, it settled for them absorbing just 46% of new dwellings.

Melbourne @ 5 Million also dropped any numerical targets for activity centres. Previously, Melbourne 2030 projected that 40% of the population growth within the established suburbs would be concentrated at relatively high densities, with the other 60% in small infill developments dispersed across the suburbs. Read the rest of this entry »

Are real estate agent fees limiting residential mobility?

Posted: November 17, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: ABS, commission, Consumer Affairs Victoria, Grattan Institute, household size, real estate agents 10 CommentsDespite an enormous increase in house prices over the last ten years, real estate commissions stayed relatively constant as a percentage of selling price. Agents consequently enjoyed a spectacular increase in the dollars earned on each sale even as the volume of sales was expanding.

In its new report, Getting the housing we want, the Grattan Institute notes real estate commissions are so big they’re a significant barrier to residential mobility in most States. This is an important public policy issue – the ABS reports that even though average household size is falling, the average number of bedrooms per household is increasing (see exhibit). Any barriers that constrain households from voluntarily moving to dwellings that better match their size should to be addressed. And the same goes for barriers that limit their ability to reduce travelling costs by moving to a new residential location.

In most industries, when firms start earning super-profits we would expect prices to be moderated by an increase in competition. However as the Institute observes, this hasn’t happened with real estate agents – competition is weak:

This is consistent with the industry elsewhere, too – the UK Office of Fair Trading recently conducted a review of UK real estate buying and selling. It found that while 32% of those who had used a traditional real estate agent believed that the fees represented either slightly or very poor value for money, 64% said that they did not negotiate a lower fee.

In Victoria, as in most States, there is no set commission, giving the impression of a lightly regulated industry. Vendors and agents are free to work out whatever arrangement they wish, whether it be a fixed sum, a sliding scale, or something else. However according to this real estate consulting group, the customary fee paid by vendors in Melbourne ranges from 1.6% to 2.5% of the selling price. This doesn’t include advertising or even a property sign – marketing is an extra cost borne by the vendor.

This introductory “how to” guide on buying and selling issued by Consumer Affairs Victoria implies an even higher commission. It illustrates a lesson on negotiation between a vendor and agent with an assumed commission of 3.3% up to $500,000 and 3.85% thereafter (p 22). That’s a $16,500 commission on a $500,000 property. I think there’s a fair chance the target market for the guide will interpret this illustration as somewhere around the “going rate”.

There’s hopefully an extensive literature that looks at why the cost to vendors has risen so much and why competition is so weak. If there is I’m not familiar with it and I don’t have time to read it anyway. It seems to me, though, that the internet should’ve reduced considerably the cost to agents of finding prospective buyers and that a good part of those savings should’ve been passed on to vendors. It also should’ve made it easier for innovators to enter the industry and set up new lower-cost business models. Read the rest of this entry »

Is the Flinders St Station design competition just about…..design?

Posted: November 16, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: architecture, competition, design, Flinders St Station, Geoffrey London, Ted Baillieu 5 Comments

Melbourne's iconic Flinders St Station (this gorgeous photo by Gillian at Melbournecurious.blogspot.com)

The Premier gave the Flinders St Station International Design Competition another nudge this week, announcing entries will be formally invited from architects mid next year, with the winner to be announced mid 2013.

Mr Baillieu indicated the project for the 4.7 ha site has two basic components. One involves “restoring and renovating the building” and the other is about “releasing any opportunities for further development”. According to The Age:

Mr Baillieu said renovation of the heritage-listed station would be very expensive, and the government was looking for ways to ”release some value” to help bankroll the development, including the possibility of a public-private partnership. A property developer will sit on the competition judging panel, as well as Victoria’s government architect, Geoffrey London.

I’ve previously questioned the sense of running this project as a design competition, but there are a couple of other aspects that also worry me.

One is that this isn’t really first and foremost an “architectural design competition”. That’s a convenient way to market the project because it sounds innocuous – everyone knows architects are sensitive characters who care about design, heritage and place.

But all the signs suggests this is really a search for commercial uses that will generate revenue for the Government – at least enough to pay for the restoration and renovation, but hopefully more. The key players will be organisations with the wherewithal to “release some value” – i.e. to identify, develop and finance new uses that generate profits.

These sorts of players are traditionally called property developers or merchant bankers, not design professionals. Architects will still have a key role in the physical expression of the new Flinders St Station precinct but they won’t be the motive force determining what sort of activities take place there.

So-called competition entries will primarily be commercial bids, rather than primarily design submissions. The novelty is the bid consortia will presumably all have to be led by architects, at least nominally.

The project is likely to be as much about the redevelopment, as the restoration, of the precinct. Redevelopment can be positive provided it is handled in a way that’re sympathetic to the transport, heritage and civic importance of this precinct. And there’s certainly plenty that needs to be done – addressing that horrible concourse-cum-food court for a start.

However redevelopment can also mean some of the values that define the precinct might be put at risk. Mr Baillieu recognises there could be new buildings but says they will have a “common sense” height limit. Hmmm……I doubt we all have the same number in mind!

Another key issue is the “competition” shouldn’t be conceived as a fishing expedition. A potential danger with competitions is officials, politicians and the public could be seduced by a spectacular proposal – a one trick pony – that fails in other important respects. The brief is thus supremely important. Read the rest of this entry »

Has the Grattan Institute got the answer to our housing woes?

Posted: November 15, 2011 Filed under: Activity centres, Housing | Tags: e-Gate, Getting the housing we need, Grattan Institute, Places Victoria, The Housing We'd Choose, VicUrban 8 Comments

Housing preferences compared with existing stock and the composition of current housing supply (by Grattan Institute)

I have to say right up-front that I’m disappointed by The Grattan Institute’s new report, Getting the housing we want. It nominally proposes ways of increasing housing supply in established suburbs, but it really just puts up the politician’s standard solution – more bureaucracy, more money, and little explanation (press report here).

In the Institute’s defence, I must acknowledge that it’s taken on a difficult task. It’s much harder to propose practical solutions than it is to analyse problems, identify key issues and propose general directions for action. And the Institute has hitherto done a good job on the latter three tasks with a series of reports under its Cities Program.

The new book by Harvard economist Edward Glaeser, Triumph of the City, illustrates the way solutions attract criticism. The book was lauded for its sophisticated analysis of the benefits of density and the need to remove the many obstacles to redevelopment. But his big idea for an historic buildings preservation quota – meaning that cities could only protect a set number of buildings each year and so would be forced to prioritise – was lambasted by all and sundry as impractical and, worse, naïve.

A lot of critics had a similar reaction to Ryan Avent’s The Gated City. Great analysis of the need to promote density, they said, but potential solutions to NIMBYism like developers compensating neighbours for the negative effects of development were criticised as unworkable and unrealistic. As soon as detailed, practical solutions are suggested, the knives come out!

So the Grattan Institute is putting its corporate head on the line with the solutions-oriented Getting the housing we want. It’s a follow-up to the Institute’s earlier report, the impressive The Housing we’d choose. The earlier report established that there’s a significant mismatch in Melbourne and Sydney between where many people actually live and where they’d like to live (see my earlier discussion of this report).

Opposition from existing residents to redevelopment proposals is a key reason for this misalignment – they don’t see the broader good and they don’t see how redevelopment benefits them. Councils tend to fall in behind residents who’re committed in their opposition to redevelopment.

The new report is on safe and familiar ground when it advocates standard stuff like code-based approval processes for small-scale development. However its headline proposal is more problematic – the Institute proposes the establishment of Neighbourhood Development Corporations (NDCs), with initial financing coming from a proposed new Commonwealth-State Liveability Fund.

The idea is NDCs would undertake large scale redevelopment projects aimed at increasing housing supply. NDCs would be “independent”, not-for-profit organisations that work in “partnership” with all tiers of government, the private sector and residents. The Institute stresses the importance of in-depth consultation and says NDCs could only “go ahead with the support of local residents”. NDCs would have to provide a diversity of housing “in terms of both type and price” and would have “temporary planning powers”.

Disappointingly, there’s not a lot of concrete information in the report on the mechanics of the proposed NDCs and Liveability Fund. And there’s little specific analysis and justification provided in support of these ideas. However the report profiles three examples of existing organisational structures similar to what’s envisaged with NDCs. These are London Docklands Development Corporation; HafenCity Hamburg, and Bonnyrigg social housing estate.

These throw more light on what the Institute envisages. They make it clear NDCs are conceived primarily as mechanisms for managing large sites like E-Gate which are invariably disused, underutilised or owned largely by government. The familiar redevelopment challenges of land assembly, existing uses and resident opposition are usually much more tractable with these sorts of sites than they are with activity centres (e.g. see discussion of proposals for Ivanhoe).

I have trouble enough with the idea that changing management structures is the broom that will sweep away all the gunk that’s holding up supply. But the trouble with having such a narrow ambit is that the potential contribution NDCs can make to increasing housing supply is necessarily more limited. Moreover, it begs the question of whether NDCs are even necessary. Read the rest of this entry »

What is the cost of commuting by car compared to public transport?

Posted: November 14, 2011 Filed under: Transport - general | Tags: BITRE, cost of commuting, distance, Public transport, time 7 CommentsThe exhibit shows that in terms of weekly household cash outlays, commuting by public transport is vastly cheaper than commuting by car, irrespective of where the commuter lives (see first three rows).

Both fixed and variable costs are much higher for cars than for public transport. For example, outer suburban households where the workers drive spend $302 p.w. compared to $41 p.w. for households whose workers use public transport.

The real killer for cars is fixed costs such as depreciation, interest and registration. These dominate variable costs like petrol, servicing and parking.

The numbers are taken from this report (which I’ve mentioned a few times recently) by the Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE). The Bureau looked at the journey-to- work costs a household of two adults and two children aged under 18 years face in Melbourne, and how they vary by location and mode.

Location is an important variable – BITRE assumes household income, level of car ownership and commuting distance/time vary substantially by location (measured here as inner city, middle suburban and outer suburban). It’s assumed households who drive own a new 4 cylinder Camry. BITRE only counts that proportion of car standing costs attributable to commuting.

Although public transport costs considerably less in terms of cash outlays, the exhibit also shows commuting by public transport takes much more time than commuting by car, no matter where a household lives. The extra time is enormous for households living in the middle and outer suburbs i.e. for more than 90% of Melburnians.

For example, the cumulative weekly commuting time for the workers in an outer suburban household who use public transport is 1,326 minutes, whereas workers in neighbouring households who drive only expend 561 minutes per week. Even members of inner city households who use public transport spend more time commuting than members of outer suburban households who drive.

BITRE value the opportunity cost of time spent commuting at average weekly earnings (just over $800 p.w.). With this assumption it’s evident time is far and away the main cost of commuting by public transport, even for households who live in the inner city. That’s a key reason why many argue the focus of public transport spending should be on improving services, not lowering or abolishing fares.

Still, notwithstanding the significant time penalty associated with public transport in Melbourne, it costs inner city and middle suburban households significantly less in total to commute by public transport than by car. Even in the outer suburbs where public transport is at its worst, the total cost on average is pretty much the same according to BITRE.

So why is public transport’s share of work journeys only 24% in the inner city, around 15% in the middle suburbs and below 10% in the outer suburbs?

That’s a good question and I think it could point to a major limitation of BITRE’s analysis – the Bureau doesn’t explain the underlying travel pattern that its analysis is based on. The reader understandably assumes commuters have a choice between two modes for the same trips, but what I suspect the numbers in the exhibit are really showing is the existing pattern of accessibility to employment in Melbourne. And that varies greatly by mode.

At present, public transport users can only comfortably get to a limited number of Melbourne’s jobs, mostly in the CBD and near-CBD. Existing public transport use reflects that limitation – most trips are CBD commutes. However given that a little over 80% of jobs are outside Melbourne City Council’s boundary and relatively dispersed – indeed, 50% are more 13 km from the CBD – most jobs are more easily accessed by car-based commuters.

So BITRE’s figures seem very limited in their application and should be interpreted with that caveat in mind. Having said that, I have some issues with the methodology anyway. Read the rest of this entry »

How much time do Melburnians spend commuting?

Posted: November 13, 2011 Filed under: Transport - general | Tags: BITRE, commute distance, commute time, travel, trip 10 CommentsOn average, workers who live in the outer suburbs commute 2.5 times further to get to work one-way than their counterparts who live in the inner city. That’s in terms of distance – probably no surprises there. However what’s not always appreciated is the extra time they spend commuting isn’t that much more – only 19% more than inner city commuters.

Since fewer than 10% of Melbourne’s workers live in the inner city (approx 5 km radius around the Melbourne Town Hall), what’s more pertinent is the average commute times of the more than 90% who live in the middle and outer suburbs. Their commutes don’t vary much – the average middle ring worker commutes for 36 minutes, the average outer suburban worker for 38 minutes. That’s just 5% more.

There’s not even a lot of variability within the suburbs either. Outer-West commuters average 42 minutes – the longest of any sub region – while the shortest commutes are enjoyed by workers resident in the Middle-North and Middle-East sub regions, who average 36 minutes. Only six minutes less.

This data is taken from Research Report 125 recently released by the Bureau of Transport, Infrastructure and Regional Economics (BITRE) – see exhibit. BITRE largely relied on data from the Vic Department of Transport’s VISTA survey. See also my earlier post on changes in commuting distances over 2001-06 (unfortunately BITRE doesn’t analyse the trend in commuting time).

The spatial regularity in the time workers devote to commuting is consistent with the idea that, on average, travellers budget a relatively fixed amount of time for travel (see here for more on travel budgets). Workers living in the inner city spend almost as much time travelling shorter distances than suburban workers because the former travel at considerably slower speeds, reflecting high levels of traffic congestion in the inner city, higher use of public transport and more walking and cycling.

At the metropolitan level, 40% of workers spend less than 30 minutes getting to work one-way and 61% less than 40 minutes. However there’s a tail of long distance commuters – 17% spend more than an hour commuting one-way. I don’t have data on this 17%, but since the average commute by public transport in Melbourne takes almost twice as long as the average car commute, I suspect many of them are train travellers (I hope to get some data on this).

The numbers in the exhibit are the result of a long-standing trend – improvements in transport infrastructure lead to higher speeds, giving residents the opportunity to increase the distance between work and home but still get there in much the same travelling time. Residents may either move house or move job, or both. This happens with both private and public transport improvements.

So the ‘headline’ implication is that, in general, improvements to infrastructure will very probably result in people travelling further to work. Where that is primarily by car it’s likely, given the technology of the existing vehicle fleet, to lead to higher resource use, more traffic congestion and make greater demands on the environment. There might be exceptions, but in general that’s what we should expect, especially given that all modes are under-priced. It’s worth noting that jobs also move outwards. Read the rest of this entry »

Are we set to commute even further?

Posted: November 10, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic, Public transport | Tags: BITRE, commuting, trip distance 7 CommentsThe Age says jobs in Melbourne are losing pace with sprawl – it cites a new study by BITRE which predicts “an increase in the average commuting distance” by 2026 and a rise in journeys to work involving a road distance of more than 30 kilometres.

If a rigorous, hard-nosed body like the Bureau of Transport, Infrastructure and Regional Economics is saying things are going to get worse in the future, it’s worth sitting up and taking notice, right? It’s true BITRE does say that, but it’s also true the media tends to err toward a sensational rather than a sober interpretation of any given facts. In this instance the story is a bit of a beat-up.

For a start, it’s hardly news that commuting distances could “increase” over a period of 15 years given the spectacular growth in population projected for Melbourne. What matters is the size of any increase – if it’s only a 1% increase over the entire period, that’s an infinitesimal 0.06% p.a. However if it’s (say) 15%, i.e. 1% p.a., that’s worth taking note of. However The Age is silent on this score.

BITRE doesn’t say anything about the size of the predicted increase either. There’s a good reason for that. BITRE’s study isn’t an authoritative prediction of future commute distances as implied by The Age’s story. It doesn’t make forecasts based on the latest data, using innovative modelling techniques and complex algorithms as one might expect. In fact the report isn’t even about the future! – it’s actually about historical population, employment and commuting patterns in Melbourne up to 2006.

The Age relies on what is in effect an ill-advised throwaway line by BITRE. The report states (p 333) that if the Victorian Government’s spatial projections of population and employment through to 2026 are realised, the likely commuting implications include….”an increase in journeys to work involving a road distance of more than 30 kilometres and an increase in the average commuting distance”. There’s no analysis or supporting information behind this assertion, so too much shouldn’t be made of it. The prominence given to it by The Age suggests BITRE should’ve thought a bit harder before including it in a report about the past and the present.

However what BITRE actually has analysed in-depth is the historical change in travel distances – and here the picture is if anything somewhat mixed. The report looks first at what’s happened over 2001-06 (see exhibit). That isn’t necessarily a guide to what will happen in 2026, but it shows how current patterns are trending. The picture it reveals isn’t one of rampant increases in commute distances but rather one of relative stability.

BITRE found the average commute in Melbourne increased from 14.7 to 14.8 km, or by just 100 metres over five years. That’s a 0.7% increase, or a miniscule 0.1% p.a. Surprisingly, the average commute increased proportionally less in the outer suburbs than in the inner city – in fact as the exhibit shows, the average commute shortened in absolute terms in the Outer South, Outer East and the Outer West.

This is the real news! It’s important because commute distances have historically increased significantly, while commute times have remained relatively stable. So reliable evidence that commute distances have stabilised, even for five years, is noteworthy. Read the rest of this entry »

Should bus lanes be shared?

Posted: November 8, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: bicycle, Bicycle Network Victoria, Bus Association, bus lane, Cycling, Hoddle St, motorcycles, RACV, scooters, Victorian Motorcycle Council 17 CommentsThe Government’s announcement this week that motorcycles will be able to travel in the bus lane on Hoddle St for a six month trial period revealed a surprising diversity of views about who should and shouldn’t be able to travel in bus lanes.

At present, only buses and bicycles can use the bus lane on Hoddle St (it runs on the south side of Hoddle between the Eastern Freeway and Victoria Parade – there’s no bus lane on the northern side).

The reporter for The Age, Jason Dowling, did his homework and canvassed a number of organisations with an interest in the matter. The Government and the Victorian Motorcycle Council evidently favour buses, motorcycles and bicycles, but:

- The RACV says the lane should be limited to buses and taxis

- The Bus Association says only buses should be permitted

- Bicycle Network Victoria is against motorcycles – it says the lane should only be used by bicycles and buses

I can’t see any problem with motorcycles and scooters using the bus lane. They’re fast enough so they won’t hold up buses and they’re small enough that they shouldn’t present queuing problems at intersections. Although they’re not without problems (noise and pollution from two strokes), they’re a relatively efficient form of transport compared to cars and low occupancy buses. If cyclists can successfully share a lane with buses that barely fit, contending with motorcycles should be a cakewalk. Motorcycles warrant space in the bus lane.

However the logic of the RACV’s argument that taxis and hire cars should be able to use bus lanes is hard to fathom. There’s no environmental or equity benefit to be gained from making a trip by taxi rather than by car. The only real difference is that in one case you’re paying for a chauffeur and in the other you’re doing the driving yourself (although for a traveller from one of the 10% of Melbourne households that don’t own a car the equation would be different).

Taxis provide an important service, but they aren’t “public transport” in the meaningful sense of a vehicle shared by multiple passengers going to multiple destinations (except sometimes at the airport). They are “public transport” only in the narrow sense that they’re available to anyone for a price. That’s also true of rental cars and I can’t see any reason why they should get access to bus lanes either.

If anything, bicycles are probably the least appropriate mode to share with buses. They’re slower and hence can potentially hold buses up, depending on conditions. In order to overtake a cyclist safely, a bus on Hoddle St will need to enter the adjoining lane, thus weakening to some degree the whole point of a dedicated bus lane. Read the rest of this entry »

Can activity centres supply enough housing?

Posted: November 7, 2011 Filed under: Activity centres | Tags: Activity centres, Banyule City Council, Edward Glaeser, Employment, Housing, Ivanhoe Structure Plan, Ryan Avent 9 CommentsMelbourne 2030 envisaged growth of high density housing and office employment within established suburbs would be located in activity centres, especially those with a rail station. In fact it specified that 41% of all dwellings should be constructed in activity centres over the period 2001-30 (with 31% in Growth Areas and the rest dispersed in small projects throughout established suburbs – at present though, about half of all new dwellings are constructed on the fringe).

Locating more intensive development within strategically important activity centres makes a lot of sense. In particular, it means a larger number of people will be within walking distance of frequent public transport, giving them an alternative to driving. Bigger activity centres should be more sustainable and might even cost the public sector less in infrastructure outlays and operating costs.

Yet it doesn’t seem to be happening – outside of the city centre, only a small number of activity centres are experiencing significant growth in multi-unit housing. Moreover, according to research by BITRE, Melbourne’s six Central Activities Areas (CAAs) and 25 Principal Activity Centres (PAC) only accounted for 3.6% of all population growth in the metropolitan area between 2001 and 2006. The number of people living in CAAs fell (by -0.3% p.a.) over the period and the number in PACs grew by just 0.8% p.a. – much lower than the growth rate for the metro area and the CBD (see exhibit).

Nor are activity centres generally successful in attracting employment – BITRE found jobs growth was actually negative in the CAAs, falling by 0.5% p.a. between 2001 and 2006. Jobs grew by 1.25% p.a. in dispersed areas outside of centres over the same period, but by only 0.5% p.a. in PACs.

There are reasons why it’s hard to attract developers to larger centres. Assembling land is difficult – existing holdings are in diverse ownership, values are often high and lots may be small. Moreover, Planning restrictions mean suitable sites are in short supply or have constrained redevelopment potential. But perhaps the key issue is opposition to development from existing residents.

As the strong reaction to Banyule Council’s proposed structure plan for Ivanhoe shopping centre shows, many residents don’t like the idea of redevelopment at up to 4-8 storeys in their local centre. They fear higher housing and employment densities will increase traffic congestion and noise and they expect the character and familiarity of their local centre will change for the worse. They see few, if any, upsides for them personally from a higher density centre.

It seems putting most higher density redevelopment eggs in the activity centres basket isn’t paying off. The politics of dealing with existing residents is simply too hard for all levels of government, whatever their colour. That’s not surprising given residents generally feel redevelopment makes them worse off and the planning system emphasises the interests of local residents.

Economists like Edward Glaeser and Ryan Avent have proposed ways that in theory might give existing residents an incentive to be more accepting of redevelopment, e.g. residents could buy the right to remain living at low density. These are novel and interesting ideas but at the present time they’re simply not going to fly politically.

Any redevelopment within established suburbs is going to be difficult. However the level of opposition can be reduced, although by no means avoided, where more intensive development is proposed for disused industrial areas. Even so, “brownfield” sites come with their own set of issues, like potential contamination and possible alternative uses.

Further, there don’t actually appear to be many brownfield sites. The authors of Challenge Melbourne – the discussion paper prepared in 2001 as part of the Melbourne 2030 process – estimated suitable brownfield sites within established suburbs have a total potential yield of 65,000 dwellings. That’s impressive, but even if all of that estimate could be realised, it’s not a big enough contribution, given the number of households in Melbourne is now projected to grow by 825,000 between 2006 and 2036. Read the rest of this entry »

What’s happening with suburban jobs in Melbourne?

Posted: November 5, 2011 Filed under: Employment | Tags: CBD, density, dispersal, Employment, Jobs, M/C Journal, suburbs 8 Comments

Density of employment in Melbourne, 2006, in one km wide circular bands by distance from CBD (jobs/km2)

The first exhibit shows the popular view of the geography of urban employment in Australia’s largest cities. It is commonly assumed the great bulk of jobs – and certainly virtually all “good” jobs – is located in the CBD.

This is an understandable view given the first exhibit shows the spatial distribution of employment density in Melbourne in 2006. It indicates the density of jobs in the Central Business District (CBD) – the first one km radius ring around the town hall – is an order of magnitude higher than anywhere else in the metropolitan area. It closely aligns with the cluster of high rise office buildings that define the CBD in the popular imagination.

Share of metropolitan employment in Melbourne in one km wide circular bands by distance from CBD, 2006 (%)

But is this is an adequate representation of the geography of employment in Australia’s second largest city? The second exhibit highlights that density is not the same as the number of jobs. It shows how employment is really distributed within Melbourne – the CBD is easily the largest single concentration of employment, but it nevertheless has only 15% of all metropolitan jobs. In fact only 28% of metropolitan jobs are located in the inner city – i.e. lie within a 5 km radius of the town hall – and 50% are located within 13 km radius.

This dispersed pattern is not recent. Melbourne was compact and dense up until the end of the nineteenth century when the appearance of mechanised transport – primarily trams and trains – enabled middle class residents to escape the crowding and congestion of the centre for the space and amenity of the suburbs. This trend was boosted dramatically after WW2 when increasingly widespread car ownership democratised access to affordable land on the urban fringe.

Firms followed a similar pattern. Initially, manufacturing and distribution firms moved to the outer suburbs so they could escape congestion in the inner city, exploit new space-intensive horizontal production methods, and be closer to the suburbanising workforce. The suburban population generated increasing numbers of jobs to service its consumption needs, amplified by the increasing level of outsourcing from the home. More recently, some higher order activities have moved from the CBD to near-CBD and inner city locations and some back office functions have moved to the suburbs.

By 1981, only 35% of Melbourne’s jobs were located within 5 km of the centre. The “average job” was 12.4 km from the centre and the “centre of mass” of employment was 5.9 km away. The trend to the suburbs was very strong over the succeeding 25 years. By 2006 just 28% of jobs were within 5 km radius and the ‘average job’ was now 15.6 km from the centre. The centre of mass had moved 2 km further outwards to the vicinity of Tooronga, 7.9 km from the CBD. Read the rest of this entry »

How far do we walk to the station?

Posted: November 2, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: bus stops, Public transport, rail stations, train, tram stops, walk distance 16 CommentsPlanners invariably work on the basis that bus and tram users will walk no more than 400 metres from home to the nearest stop. It’s known travellers will walk further to catch a train, so the maximum walk distance to a station is accordingly usually taken as 800 metres.

So it’s interesting to look at what travellers actually do. Data from the VISTA travel survey shows the median walk distance to the bus in Melbourne is 500 metres, with a quarter walking more than 800 metres. Half of Melbourne’s train travellers walk more than 800 metres and a quarter more than 1.3 kilometres! Hence bus and train users in Melbourne walk much longer distances than the standards assume.

If the VISTA methodology is right, these findings can be interpreted a number of ways. One is that travellers have to walk unreasonably long distances in Melbourne, perhaps because bus and train coverage is too sparse, or stops are poorly located. Alternatively, it could show travellers are prepared to walk much further than planners have historically assumed (I’m sure some would even argue the exercise is good for them!).

Standards like 400/800 metres are often justified on the grounds that if travellers have to walk any further, they will choose to drive instead, thus lowering the demand for public transport. It’s argued that trains can command longer walk distances because experience shows travellers will walk further if they’re taking long trips, or if the mode is fast (train trips tend to be much longer than other modes, both public and private, and also faster because they have their own dedicated right-of-way).

While that’s all fair enough, I don’t think it draws out the policy implications as clearly as it might. I think there’s another way of interpreting the data on trains in particular. Trips by train are indeed longer and faster than those by other modes, but the key reason travellers walk long distances to stations is they have to – they don’t have a choice.

That’s primarily because the key market for trains is workers travelling from the suburbs to the city centre. Driving simply isn’t a realistic option for most of these commuters – parking in or close to the centre is too expensive and the combination of distance and traffic makes driving too slow and too costly. Limited parking means it’s also hard to drive to the station. In addition, there are all those “captive” travellers who don’t have access to a car or can’t drive (e.g. students) but have high value trips to make.

In other words there are many trips where the car is simply not a realistic alternative to the train. In these cases the maximum distance people are prepared to walk (or have to walk!) is much longer than the standard 800 metre maximum. Not having an alternative, train users walk as far as they have to.

In fact the mean distance train travellers walk from home to the station in Melbourne is one kilometre. That’s a lot further than the median (800 metres) and suggests there’s a long tail of travellers who walk a very long distance from home to the station.

Accepting the legitimacy of longer walk distances could possibly have implications in a number of areas, for example in the design of feeder bus services, the spatial extent of development around stations, and in some cases even the spacing of stations. But most stations are already a considerable distance apart, so the practical implications are probably limited.

However where this way of looking at the issue might have particular relevance is in the spacing of tram stops. Unfortunately I don’t have any data to hand on actual tram walk distances in Melbourne, but my understanding is they too are longer than the 400 metre standard suggests. Further, many tram stops in Melbourne are closely spaced – for example, in the inner eastern suburbs they are every 200-300 metres. Read the rest of this entry »