Is Warne putting the right spin on cycling?

Posted: January 23, 2012 Filed under: Cycling 4 CommentsYou can read the first post for 2012, Is Warne putting the right spin on cycling?, at my new home at the giant Crikey media conglomerate. Please bookmark the new site. I’m looking at ways to bring existing e-mail subscribers across (hopefully) with as little pain as possible. All comments should now be made at the new site.

Are helmet laws suppressing cycling?

Posted: December 13, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: bicycle, Canadian Business Network, Chris Rissell, Health Promotion Journal of Australia, mandatory helmet law, Metlink, survey, Sydney, World Bank 59 CommentsA new Australian study has thrown more fuel on the fiery debate about whether or not bicycle helmets should continue to be mandatory. Its headline claim is 23% of Sydneysiders say they would cycle more if they weren’t obliged by law to wear a helmet.

This isn’t merely saying that some people would prefer to cycle without a helmet – it’s claiming the law actually suppresses cycling.

I lean toward the school of thought that says mandatory helmets probably do more harm socially than good, but as I’ve said before, it’s not the sort of issue that I would want to die in a ditch over. However if there were reliable evidence that compulsory helmets actually restrain cycling, that would require a rethink.

The research was undertaken by Professor Chris Rissell and his colleague, Li Ming Wen. It is published in the latest edition of the Health Promotion Journal of Australia, under the snappy title, The possible effect on frequency of cycling if mandatory bicycle helmet legislation was repealed in Sydney, Australia: a cross sectional survey.

It’s a brief and easy to read article but a summary by Professor Rissell was published on The Conversation last week, Make helmets optional to double the number of cyclists in Australia. Professor Rissell is a self-confessed cycling advocate and firmly in the activist “repeal” camp on helmets.

He and his colleague surveyed 600 Sydney residents aged 16 years and over. They found one fifth of respondents “said they would cycle more if they did not have to wear a helmet, particularly occasional cyclists”. They conclude that:

While a hypothetical situation, if only half of the 22.6% of respondents who said they would cycle more if they did not have to wear a helmet did ride more, Sydney targets for increasing cycling would be achieved by repealing mandatory bicycle helmet legislation. A significant proportion of the population would continue to wear helmets even if they were not required to do so.

Regrettably, I don’t think this study adds anything to our knowledge of whether Sydneysiders would ride more if helmets weren’t compulsory. They might, but then again they might not. The trouble is the survey relies on a hypothetical situation: “Would you cycle more often if you didn’t have to wear a helmet? Yes or No?”.

Hypothetical survey questions are notoriously unreliable. I’m not picking on the anti-mandatory helmet brigade here – I also took Metlink to task earlier this year for trying to make grandiose predictions about future public transport patronage based on a similarly unreliable methodology.

It’s standard practice to avoid hypothetical questions in surveys. Consider this advice from The World Bank publication, The Power of Survey Design:

Hypothetical questions, especially, should be avoided. People cannot reliably forecast their future behaviour in a hypothetical scenario. Thus, the questionnaire design should make careful use of this style of question.

Hypothetical questions are especially problematic when respondents are asked to predict an activity they’ve had little experience of. The Canada Business Network advises questionnaire designers, if possible, to “avoid hypothetical or future intentions questions:

Hypothetical questions force the respondent to provide an answer to something he or she may never have thought about and, therefore, the respondent may not be able to provide an accurate response.

The authors should’ve been alerted that all might not be right when they found 40% of those who say they’d cycle more if helmets weren’t compulsory, also say they support mandatory helmet legislation. Yes, there’re scenarios where it’s conceivable someone could hold both views simultaneously, but 40%?! Read the rest of this entry »

Mandatory bicycle helmets: does correlation mean causation?

Posted: November 1, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: bicycle, Cycling, helmet, mandatory. law, Pucher and Buehler, safety 37 CommentsIt’s evident from the response to my article two weeks ago (Is the mandatory helmet debate a distraction?), that some people still see compulsory helmets as one of the major obstacles, perhaps even the main obstacle, to significantly higher uptake of cycling in Australia. So I want to look at the main arguments for repealing the compulsory helmet law.

As I’ve said before, I accept that mandating helmets in the early 90s was arguable policy, at least in the case of adults. If it were proposed for the first time today, I doubt it would get up (except for children). So I don’t think those who advocate repeal are necessarily “wrong”.

But in my view the helmet law is not the main thing holding cycling back in this country – it doesn’t even come close. And since it’s got virtually no traction politically, it’s also a waste of energy. Ultimately it distracts from the key issue – the danger, whether perceived or real, of cycling in traffic.

A key argument made by many repeal advocates is that countries without mandatory helmet laws have high bicycle use. Australia, in contrast, has both low mode share and draconian helmet laws; ipso facto, they say, mandatory helmet laws are the key problem.

What I think is happening here is the familiar problem of confusing correlation with causation.

There’s no doubt bicycle use in Australia is indeed low compared to some other countries. For example, according to Pucher and Buehler in Making cycling irresistible: lessons from the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany, bicycles capture 27% of all trips in the Netherlands and 18% in Denmark, but a mere 1% in Australia (see exhibit). And there’s no doubt helmets aren’t considered important in these countries – in the Netherlands, for example, less than 1% of adults and only 3-5% of children choose to wear a helmet when cycling.

But does the law on helmets explain why cycling is so much more popular in these countries than it is in Australia?

The first thing the repeal advocates should ask themselves is this: why are only 1% of trips in the UK taken by bicycle even though helmets aren’t mandatory in that country? That’s no better than here! Or why is cycling’s mode share only slightly better in Ireland and Canada than it is in Australia, even though these two countries don’t have mandatory helmet laws? Clearly, whatever the explanation is for the comparatively low rates of cycling in these countries, it has nothing to do with any compulsion to wear a helmet.

They should also ask themselves why there are such enormous differences between countries where helmets aren’t mandatory. The fact that bicycle use is more than twice as high in the Netherlands as it is in Germany – and nine times higher than it is in France and Italy – suggests pretty clearly that there are other highly influential factors affecting the propensity to cycle that have absolutely nothing to do with helmets.

Helmet policy doesn’t explain why bicycles capture 34% of trips in Munster, but 13% in Munich. Or why the corresponding figure for Groningen is 37% compared to 10% in Heerlen; or 20% in Bruges but 5% in Brussells; or 19% in Salzburg but 3% in Wien. Read the rest of this entry »

Do drivers make cycling less safe?

Posted: October 24, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: behaviour, bicycles, Cycling, drivers, Marilyn Johnson, Monash University Accident Research Centre, road safety 20 CommentsThis important article makes two key points about cycling in Australian cities:

- The main danger to cyclists comes from drivers

- The key reason people don’t cycle more is concern about safety on the roads

The article reports on research by Marilyn Johnson, a research fellow at the Monash University Accident Research Centre. She attached a video camera to the helmets of a small number of cyclists and studied their everyday interactions with other road users (see exhibits).

A key finding is drivers are responsible for 87% of road “incidents” i.e. a near-crash where at least one party has to take evasive action. In 74% of those events, she says, the driver cut the cyclist off, turning in front of the cyclist without either providing enough space, indicating effectively or doing a head check.

The behaviour of drivers was safe for themselves and other drivers, but not for cyclists:

The role of driver behaviour in cyclist safety was found to be more significant than previously thought. Previously, the emphasis was on how cyclists needed to improve their behaviour to improve their safety……Drivers need to be more aware of cyclists on the road. It is essential for cyclist safety that drivers look for cyclists before they change their direction of travel, particularly when turning left.

Dr Johnson also cites a joint study by the Cycling Promotion Fund and National Heart Foundation which surveyed a random sample of 1,000 adults nationally about their attitudes toward cycling. According to this report on the study, “overwhelmingly, unsafe road conditions were the No.1 reason why people weren’t using their bikes as transport, followed by the speed of traffic and a lack of bike paths”.

Although the number of cyclists involved in the study to date and the range of environments is small, I think Dr Johnson’s research is highly suggestive. It underlines again the importance of focussing attention on the key issues that affect cycling and of not getting distracted by side issues.

What were they thinking?

Posted: October 22, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: advertising, Cycling, marketing, Motor Accident Commission, Public transport, responsible driving, South Australia 16 Comments This is not a joke – this is a real graphic from the SA Motor Accident Commission’s new marketing campaign aimed at discouraging young drivers from doing irresponsible things like speeding or drink-driving.

This is not a joke – this is a real graphic from the SA Motor Accident Commission’s new marketing campaign aimed at discouraging young drivers from doing irresponsible things like speeding or drink-driving.

The core idea is life is very bad without the ability to drive. You might, for example, end up having to walk, use public transport, or – apparently the uncoolest thing imaginable – ride a bicycle!

This TV advertisement shows boys who cycle are an absolute turn-off so far as girls who drive are concerned.

And if you lose your license, you’ll really know you’re screwed if:

“you’re caught in an electrical storm, you’re halfway home and you’re on a bike”, or

“you keep catching your hot date staring at your helmet hair”, or

“the creepy guy on the bus has just made eye contact”, or

“after lining up for 10 minutes in the rain the drive thru girl says: sorry we don’t serve pedestrians”

Now perhaps the Motor Accident Commission’s research shows the prospect of cycling or using a bus is so horrendous for the target market that it is the most effective way of incentivising more responsible behaviour. Perhaps.

But even if that’s the case, it comes at the cost of demonising modes that have to play a much more important role in our cities both now and in the future. If the campaign is actually effective, it could be doing incalculable long-term damage to the way alternative modes are perceived.

I’d be surprised if the creative talent of Adelaide couldn’t come up with a campaign that achieves the responsible driving objective without undermining another important dimension of transport policy. However I’m not quite so confident about the judgement of politicians and bureacrats who would let this sort of message through!

Is the mandatory bicycle helmet debate a distraction?

Posted: October 19, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: bicycle, CARRS-Q, Cycling, Deakin University, helmet, Jan Garrard 36 CommentsThere is an interesting new article on The Conversation by Deakin University’s Dr Jan Garrard, which asks the important question: Why aren’t more kids cycling to school?

Dr Garrard analyses the key warrants for increasing the proportion of children who cycle (and walk) to school; identifies the main obstacles; and sets out some actions that might help to reduce car use for school drop-off and pick-up. I generally agree with her conclusions but disagree with the emphasis she gives to childhood health and obesity as a warrant for encouraging more cycling to school.

I was going to write about that until I was distracted by various comments on her article relating to the desirability or otherwise of mandatory bicycle helmets. This topic is becoming an increasingly familiar pattern in cycling debates – it seems there are people who think abolishing the compulsion to wear a helmet when cycling is the silver bullet that will turn Australian cities into “new Amsterdams”.

I accept the mandatory helmet issue is one factor that bears on the level of cycling, but quite frankly I think it’s a sideshow. As I’ve argued before, my feeling is that even in the unlikely event helmets were made discretionary, the great bulk of existing and prospective cyclists would make the rational decision and elect to wear a helmet. There is good evidence to support the intuition that cycling with a helmet is safer than cycling without one.

To date I’ve accepted the proposition that at a social level the exercise disincentive effect of mandatory helmets probably outweighs their protective benefits. The undeniable drop in cycling that immediately followed the introduction of mandatory helmets seems to support that view. However a new study by the Centre for Accident Research and Safety – Queensland (CARRS-Q), Bicycle Helmet Research, suggests that might not be the case. The authors say:

It is reasonably clear (the mandatory helmet law) discouraged people from cycling twenty years ago when it was first introduced. Having been in place for that length of time in Queensland and throughout most of Australia, there is little evidence that it continues to discourage cycling. There is little evidence that there is a large body of people who would take up cycling if the legislation was changed.

The CARRS-Q study also concludes that “current bicycle helmet wearing rates are halving the number of head injuries experienced by Queensland cyclists”. It says this finding is consistent with published evidence that mandatory bicycle helmet wearing legislation has prevented injuries and deaths from head injuries.

In my view the number one deterrent to higher levels of cycling isn’t compulsory helmets, it’s concerns about safety, whether real or perceived. Addressing safety concerns will require more infrastructure like segregated bike lanes. However that’s expensive – realistically, any significant increase in cycling means bicycles will have to share road space with other vehicles for many years yet, so the priority should be to get more respect and consideration from drivers.

Drivers don’t see cyclists as valid and legitimate road users. That’s not because cyclists dress in lycra, flout the road rules, wear helmets or don’t pay rego – it’s because drivers think roads are for motorised vehicles only. Drivers think they “own” the roads. This perception is the key issue that needs to be addressed to make cycling safer and hence more appealing. I’ve outlined before how I think this challenge might be addressed through driver education and licensing; through schools; through media campaigns; and through changes to the law. Read the rest of this entry »

Is the Auditor-General on-track with cycling?

Posted: August 20, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: Cycling, efficiency and effectiveness review, Victorian Auditor-General, Victorian Cycling Strategy 12 CommentsIt’s a long time since I’ve read an official report as both extraordinary and disappointing as the report released last week by the Victorian Auditor-General, Developing cycling as a safe and appealing mode of transport.

This effectiveness and efficiency review of the former government’s 2009 Victorian Cycling Strategy is extraordinary because it takes the Brumby government to task for its extravagant claim that the Strategy would “grow cycling into a major form of public transport”, but then failed to put in place the steps the Auditor-General believes are necessary to achieve this ambitious goal.

He makes it clear the sorts of actions he thinks are required are those pursued since the 1970s in countries like Denmark, The Netherlands and Germany where bike’s mode share is now as high as 38% of all trips (but also as low as 3% e.g. Wiesbaden). Those actions include education and promotion, but the key ones are segregating cyclists from cars and making cars slower and less convenient.

As I read the Victorian Cycling Strategy – which is only 20 months old – this sounds like a bit of fit up, but since the Department of Transport has signed off on the Auditor-General’s review, I’ll let that lie.

Governments in Victoria might need to be careful. Judging by this report the Auditor-General seems to be in no mood to tolerate the entrenched practice of blithely setting exaggerated and inflated goals with little real commitment or accountability for realising them. On the other hand, the Baillieu government has “discarded” the Strategy, so perhaps that emboldened the Auditor-General in this particular instance.

Either way, I applaud the Auditor General for his evident intolerance of bullshit (I hope he takes the time to compare some of the purple prose written about public transport against what’s actually being done in practice). Governments should and can do much more to promote cycling. So far there’s lots of lip service but not much action.

But having said that, the Auditor General’s report is also disappointing because its not without its own failings. For a study that cost nearly $400,000, it is a surprisingly lightweight document. I have to hope there’s much more to it, but quite frankly it reads like someone merely got the Department of Transport to run some basic data off VISTA and read Pucher and Buhler’s influential paper, Making cycling irresistible. If there were such a thing as an audit of Auditor-General’s reports, I reckon this one would be found wanting.

I was doubtful of the report’s technical quality from the get-go when I read the claim in the first paragraph that “cycling offers benefits over other forms of transport because it reduces traffic congestion…”. No it doesn’t, no more than building freeways or improving public transport do. What cycling can do is increase the number of people who can get to a destination despite traffic congestion – which is a huge positive – but it won’t reduce congestion.

A key criticism the report makes is the Strategy prioritises inner city work journeys over other trips. Since 78% of car journeys up to 4 kilometres long (and 80% of car journeys between 4 and 10 kilometres) are in middle and outer Melbourne, the Auditor-General reckons the Strategy should have addressed this potential more vigorously. This simplistic view is symptomatic of much of the report. What it fails to recognise is the necessity of prioritising scarce resources like money and political capital. The fact is inner city work trips in the Melbourne of today are more amenable to cycling than suburban shopping trips.

Another shortcoming is the presumption that to grow cycling into a major form of transport we can and should do exactly what successful European cities like Copenhagen have done. But is “a major form of public transport” the 37% of all trips that Groningen has achieved, or the 3% of Wiesbaden? This is the Auditor-General and he’s finding fault with government policy – expecting some measure of precision isn’t unreasonable.

The fact that those cities have much higher bicycle use than Australian or US cities is a very important and pertinent piece of information, but it doesn’t automatically follow that if we do what they’ve done we’ll get the same outcome. In fact it doesn’t even follow that it’s practical, realistic or feasible for us to do what they’ve done.

There’s a long history of assuming what works overseas will work here. For example, in common with many other countries, Australian governments and universities have attempted many times over the last 30 or so years to replicate the success of places like Silicon Valley by establishing technology parks close to universities. Yet every analysis I’ve seen has shown these attempts to be unmitigated flops – at best, we’ve ended up with cookie-cutter business parks rather than the anticipated hotbeds of innovation fuelled by university-business interaction. The fact is places like Silicon Valley are the result of a very special set of circumstances that can’t easily be replicated elsewhere. Read the rest of this entry »

What is the key challenge for cycling policy?

Posted: August 3, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: bicycles, Bojun Björkman-Chiswell, Cycle Chic, Cycling, license, mandatory helmet, pedestrians, registration, safety 26 CommentsThere’s been a spirited and useful debate in Victoria over the last 12 months about the rights and wrongs of mandatory helmets, but now it’s time to move on to the main game. This column in The Age (and especially the associated comments) by Bojun Björkman-Chiswell, the founder of website Melbourne Cycle Chic, is a reminder that compulsory helmets aren’t the key obstacle to the wider uptake of cycling in Melbourne.

Ms Björkman-Chiswell describes how she was recently hit by a car while cycling in the very city that only days before had been pronounced by Lord Mayor Robert Doyle and Premier Ted Baillieu as a ”bike city”. Melbourne is most definitely not, she avers, a bike city. “It is a city where people who wish to use a fast, free, non-polluting, peaceful and convenient mode of transport are subjected to harassment, culpable driving, injury and death….”.

The shit hit the fan however when she let on, seemingly as an afterthought, that she wasn’t wearing a helmet:

You’ll be pleased to know, Cr Doyle and Mr Baillieu, that despite my accident, my head is fine, but my neck is wrenched, my ankle swollen, my knee strained and my left shoulder, rib cage and thigh bruised, and I don’t wear a helmet.

A string of commenters took her to task for those last five words. As one said: “Great article, but you totally lost all your cred without the helmet. No wonder motorists don’t take you seriously”. And another: “How sad that you won’t protect yourself when you KNOW how idiotic most of the car drivers are”. And this one: “You’re insane if you don’t wear a helmet riding a bike in any Australian city (this isn’t the Netherlands). Plus there is the little matter that it is illegal not to wear a helmet”.

The key issue at the moment for Melburnians interested in cycling isn’t compulsory helmets – that’s a sideshow – it’s safety. While the weight of evidence suggests the exercise disincentive effect of helmets probably outweighs their protective benefits, our starting point is not an ideal world. Melbourne’s streets are dominated by cars. An individual contemplating cycling on the city’s roads has to have very special regard for the dangers of traffic. Cycling might not be as dangerous as people imagine, but it’s the perception of danger that holds prospective cyclists back.

Even if helmets were made discretionary, my feeling is the great bulk of Melbourne’s cyclists would make the rational decision and elect to wear a helmet. Just as importantly, I suspect that the next ‘cohort’ on the verge of taking up cycling (given an appropriate nudge) would also overwhelmingly choose to wear a helmet. Some might prefer not to, but on Melbourne’s roads you need every little advantage you can get.

As Paul Keating might say, compulsory helmets is a second order issue at this time. So let’s move on and give much-needed attention to the current number one issue, improving safety. So far that’s mainly meant providing dedicated infrastructure like bike lanes. More infrastructure is indeed needed – much more – but the task of effectively segregating bicycles and motorised traffic is mammoth.

The reality is cycling can only increase its share of travel significantly in Melbourne if it shares road space with cars, buses, trucks and trams. What’s really needed to make cycling safer is more respect and consideration from drivers.

The core issue is drivers don’t see cyclists as legitimate road users. I don’t think that’s got a lot to do with cyclists not being licensed, bicycles not being registered, riders wearing lycra, or cyclists flouting the road rules. I think its fundamentally because motorists simply see roads as exclusively for their use and cyclists, like pedestrians, don’t belong on them. That’s what drivers have always been told and that’s what they’ve always believed. Read the rest of this entry »

Do as many Melburnians cycle to work as Americans?

Posted: July 5, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: Aaron Renn, bicycles, commuting, Cycling, Kory Northrop, Melburnian, mode share, Nancy Folbre, Portland, Portlander, Portlandia, The Urbanophile 7 CommentsThis remarkable map, via Nancy Folbre, shows cycling has a non-trivial share of commuting in at least ten cities in the automobile-centric USA. In Portland OR, 6% of workers commute by bicycle and in Minneapolis 4%. Cycling’s mode share is 3% in Oakland, San Francisco and Seattle, and 2% in Boston, Philadelphia, Washington DC, New Orleans and Honolulu.

How does Melbourne compare with US cities? These ten cities are central counties so there’s no point in comparing them with the entire Melbourne metropolitan area (where bicycle’s share of commutes is 1%). In order to arrive at a fair basis for comparison, it’s necessary to look at bicycle’s share of commutes in Melbourne’s inner city and inner suburbs.

So I’ve summed the Statistical Subdivisions of Inner Melbourne, Moreland, Northern Middle Melbourne and Boroondara. They give me a combined area – which I’ll call central Melbourne – of 313 km2 and a total population of 804,112. That’s a little smaller geographically than Portland, which occupies 376 km2, but it’s a much larger population than Portland’s 566,143.

Cycling’s share of commutes in central Melbourne is 2.81%, which seems pretty good compared to most US cities. However given it’s substantially higher population density, it’s surprising that central Melbourne falls well short of Portland, where 5.81% of commutes are by bicycle. Some allowance has to be made for different methodologies – for example, the Portland figures are 2009 and the Melbourne figures are from the 2006 Census – but that’s not enough to explain a gap this size.

My family and I spent a week in Portland in 2009 and I don’t recall any obvious physical differences that favour cycling relative to Melbourne. In fact at first glance Portland doesn’t look especially promising for bicycles. It’s hillier than central Melbourne, it’s colder and it’s lower density. I doubt that Portland is better endowed than central Melbourne with commuter-friendly cycling infrastructure either.

In some ways Portland actually belies its status as the darling of new urbanism. It’s spaghettied with freeways and in many places doesn’t have footpaths. Even with the new light rail system, public transport has a substantially lower share of travel than in Melbourne.

I think a better explanation for cycling’s high commute share is the special demography of Portland. Aaron Renn puts it this way:

People move to New York City to test their mettle in America’s ultimate arena. They move to Silicon Valley to strike it rich in high tech. But they move to Portland for values and lifestyle; for personal more than professional reasons; to consume as much as produce. People move to Portland to move to Portland.

He cites Joel Kotkin, who reckons “Portland is to today’s generation what San Francisco was to mine: a hip, not too expensive place for young slackers to go”. I like the way the comedy TV show Portlandia put it, describing Portland as the place “where young people go to retire”. Read the rest of this entry »

Is bike-share the safest way to cycle?

Posted: June 23, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: accidents, Capital Bikeshare, Cycling, Melbourne Bike Share, safety, Streetsblog, Velib 5 Comments

Abbott recants and embraces a tax on carbon - "if you want to put a price on carbon why not just do it with a simple tax?"! The Melbourne Urbanist is not politically partisan, but gives credit to any politician who shows this sort of courage! (wow, the things they can do these days with a bit of smoke and a few mirrors! Remarkable)

According to this story, riders of share-bikes are involved in fewer accidents and sustain fewer injuries than cyclists who ride their own bikes. The author provides an impressive array of examples.

In Paris, Velib riders account for a third of all bike trips but are involved in only a quarter of all bike crashes. In London, the first 4.5 million trips on the new “Boris bikes” resulted in no serious injuries, whereas the same number of trips on personal bikes injured 12 people. The situation in Boston DC is similar:

In its first seven months of operation, Capital Bikeshare users made 330,000 trips. In that time, seven crashes of any kind were reported, and none involved serious injuries. In comparison, there were 338 cyclist injuries and fatalities overall in 2010, according to the District Department of Transportation, with an estimated 28,400 trips per weekday, 5,000 of which take place on Capital Bikeshare bikes.

So it seems likely that Melbourne Bike Share’s unloved Bixis are at least a safer way to travel than ordinary bicycles. The implication of the story is that upright bicycles may be safer than the racers and mountain bikes we’re used to in Australia. That might sound plausible on first hearing, but I’m not so sure.

What strikes me straight up about these numbers is that relative trip rates don’t provide a valid basis for comparison. The only sensible measure is “accidents per km” because it indicates the relative exposure to potential accidents. Share-bike riders pay more the longer they rent the bike, so they have an incentive to take relatively short trips. On the other hand, I think it’s very likely personal riders travel longer distances – e.g. for commuting or leisure – and accordingly have greater exposure to potential accidents.

That doesn’t “disprove” the claim that share-bikes are safer than ordinary bikes, it just says the quoted statistics don’t tell us if they are or they aren’t. But for the sake of argument, let’s suppose share-bikes are safer, even if the difference is less dramatic than the quoted numbers suggest (intuitively, I suspect they actually are a bit safer on a per km basis). But if so, what is the underlying reason? Is it some intrinsic quality of share-bikes? After all, they’re heavier and therefore slower than ordinary bikes so that might explain it. Another reason might be their more upright riding position, which makes them more visible to motorists.

These explanations could have some role, but I think there are more obvious reasons why share-bikes might have a lower accident rate (if in fact they actually do). Read the rest of this entry »

Can cyclists and pedestrians coexist?

Posted: June 9, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: 3 way street, bicycle, conflict, Cycling, pedestrians 28 CommentsThis fascinating video by designer Ron Gabriel shows the problems caused by errant motorists, pedestrians and cyclists at an intersection in Manhattan. Each class of traveller has members who act selfishly and inconsiderately toward the others. This is just one of 12,370 intersections in New York City – they are the site of 74% of traffic accidents in the City, according to the video.

Cars are the biggest problem because they can do the most harm to other users, but at least they usually keep off areas dedicated exclusively to walking. A new problem emerging with the increasing popularity of cycling is bikes intruding into areas like footpaths, squares and promenades usually considered the sole domain of pedestrians. I wouldn’t dare make a sudden move when walking along the river at Southbank without checking first to see if there’s a cyclist threading his way through the throng who might possibly collect me!

Mounted cyclists do not mix well with pedestrians on footpaths. Those who cycle in crowds at speed are of course more dangerous, but speed is a relative term. I don’t relish being stabbed by a Shimano 105 shifter carrying the momentum of an 80-90 kg man, even if it’s only moving at 10 kph. My greatest worry was when my kids were very young and likely to run about unpredictably – they should be able to do that in a pedestrian area without the risk of being collected by a bike. In fact I think the greatest risk is from 10 kph cyclists who track too close to walkers, leaving no room for avoiding an incident with pedestrians who don’t behave as predictably as the cyclist (incorrectly) anticipated.

As I understand it, cycling in pedestrian areas is illegal for anyone over the age of twelve unless they’re supervising a child who’s also cycling. It isn’t just an issue of endangering pedestrians – it also makes walking a less enjoyable and relaxed way of getting from A to B. What’s more, like cyclists running red lights, it can potentially reinforce the negative perceptions and rhetoric of the anti-cycling brigade. The cyclist who ignores red lights really only puts himself at risk, but if he cycles in pedestrian areas he can put others at risk. Read the rest of this entry »

Is Bicycle Victoria (membership) worth it?

Posted: May 22, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: Bicycle Victoria, Cycling, membership, Public Transport Users Association 10 CommentsIt’s with some regret I report I’ve let my membership of Bicycle Victoria (BV) lapse. I had a call last week from one of BV’s sales people asking me if I would front up $150 to continue my family membership for another year. I said no.

In 2009 my family membership was $120. Last year it jumped to $135, this year it’s $150! That’s more than 10% escalation per annum. Why is this sort of increase necessary? I could downgrade to a two person household membership for $125 or a one person membership for $105 but in my opinion that’s still too much — and in any event I wanted a family membership.

I know some will say that’s what effective lobbying and community education costs in this day and age. What’s a hundred and fifty bucks, they’ll say, in the scheme of things when you compare it to the good works BV does? I know the “if you pay peanuts, you get monkeys” argument. And some will say I’ve lost access to BV’s third party property insurance and legal defence services. But it’s still too much.

Most every non-profit I see these days is a “professional” organisation with the culture that implies – relatively high salaries at the top, expense accounts, frequent travel, and so on. Many function in part as out-sourced providers of government programs so perhaps it’s not surprising that they tend to mimic public sector standards and practices. While I have no reason to doubt the competence and dedication of BV’s staff, I fear it’s becoming more about bureaucracy than bicycles.

Have a look at BV’s web site to see just how many paid staff BV has. This is a big organisation. Annual revenue is $11.7 million. There’s the CEO and seven general managers. Then there are seven teams. There are five staff in the Ride2School team, seven in the Facilities Development Team, six in the Riders Team, four each in the Finance and the Publications teams, five in the Events Team and three in the Rider Services Team. Some of these staff are supported by “behaviour change” grants to deliver particular programs on behalf of government. Perhaps some of them are part-time, but I don’t think there’s any doubt this is now a big organisation.

My interest in supporting BV is not how big it can get, but what it can do to improve conditions for cyclists. The key to that is lobbying state and local governments and educating the community about cycling. That’s a task that requires a coordinator to act on behalf of cyclists because it can’t be done by the market. So we need a BV in some incarnation. But like so many organisations, BV seems to have grown to take on a raft of other functions, many of them aimed at generating more revenue – in fact membership fees now make up only 19% of BV’s revenue. But more revenue for what?

The 2009-2010 Financial Statement and the 2009-2010 Annual Report indicate that close to half of BV’s expenditure goes on conducting rides. These are a big focus of attention – they account for 48% of expenditure (and 58% of revenue). That’s nice, but my membership fees aren’t needed to conduct operations that cover their costs and could in any event be mostly left to the private sector. Nor am I interested in forking out $150 a year so the government has an organisation that can deliver behaviour change programs on its behalf or so that BV can provide consulting services on a commercial basis. And quite frankly if it wasn’t “free”, I wouldn’t choose to buy the bi-monthly Ride On magazine, which is essentially a promotional vehicle with little solid content. Read the rest of this entry »

Should wearing bicycle helmets be voluntary?

Posted: May 17, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: accidents, compulsory bicycle helmet, Cycling, fatalaties, mandatory 25 CommentsI wouldn’t cycle in Melbourne without a helmet and I think anyone who chooses to cycle on the roads of our fair city without one is either an actuary or a statistics nerd. But as this raging debate shows, many people evidently would.

One reason I’m risk-averse about cycling is the experience of ‘dropping’ my bike with my son strapped in the child seat when he was two. While it was a low-speed accident, he banged his head on the road – fortunately it was encased in a helmet. Would he have been injured if he wasn’t wearing one? I don’t know for sure but I’m very glad I didn’t have to find out.

Another reason is I once worked with a woman whose teenage brother died many years before when he fell off his bike and hit his head on a gutter. This happened back in the days before anyone even thought to wear a helmet. Probably most importantly, I have a relative, a surgeon, who worked on a bicycle trauma study in Qld in the 80s and impressed on me the severity of head trauma suffered by cyclists, almost all of them children.

I wear a helmet because it’s a limited form of insurance against an unlikely but potentially catastrophic event. Like any insurance, the most likely outcome is I’ll pay more in ‘premiums’ than I’ll get back in ‘pay-outs’, but it’s protection against the remote possibility of absolute disaster. I know it won’t offer anything like the protection of a motor cycle helmet, but it will help in some sorts of low-impact events that might otherwise be deadly.

A helmet has no effect on my propensity to cycle. I’m a regular cyclist who commuted for many years, and I’ll always insist on wearing one. But making helmets mandatory for all cyclists is another matter altogether. While there’s still plenty of dispute, from the evidence I’ve seen, the social benefits of mandating helmets are probably out-weighed by the costs.

The key argument against compulsory helmets is they discourage people from enjoying the health benefits of cycling and from generating the associated environmental payoffs. It seems likely these foregone benefits exceed those from avoided head trauma. Also, discouraged riders diminish the number of cyclists on the road and thereby make cycling in traffic more dangerous for all riders.

The “discouraged cyclist” effect manifests in a number of ways. There’s unwanted ‘helmet hair’. Always having a helmet on hand can be inconvenient. Helmets are uncool in some demographics, particularly among children. In hot weather they can be very uncomfortable. Probably most importantly, making helmets compulsory helps create the idea that cycling is inherently more dangerous than it actually is.

The debate isn’t really about the value of choosing to wear a helmet, it’s about whether or not the net benefits at a social level warrant compelling everyone to wear one. I subscribe to the view that any restriction on personal behaviour needs to have pretty strong and unambiguous net benefits to be justified.

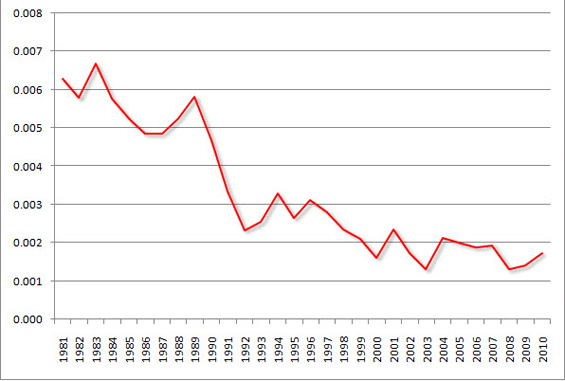

The circumstances at the time bicycle helmets were made mandatory (1991 in Victoria) were very different to today. The fatality rate from road accidents was far higher than it is now – there were 13.7 fatalities per 100,000 population in Australia in 1990, versus 6.8 in 2009. Probably most importantly, cycling was seen as something only children – vulnerable and immature – did on a serious scale. New research in the 80s on cycling-related head trauma, mostly among children, made compulsory helmets an easy and widely-applauded decision. At the time, the benefits doubtless seemed strong and unambiguous. Read the rest of this entry »

Could Yarra Boulevard be a ‘Bicycle Boulevard’?

Posted: March 9, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: Baillieu Government, bicycle boulevard, Copenhagen lane, Cycling, green street, road space sharing, Yarra Boulevard, Yarra Trail 8 CommentsThe State Government could strike a blow for cycling in this city if it were to declare Yarra Boulevard at Kew a ‘Bicycle Boulevard’.

This road is currently used by a range of recreational cyclists for riding and occasionally by some clubs for competitions. Although it doesn’t have heavy traffic there are enough cars and motorcycles to create a hazard for those on bicycles.

Drivers expect cyclists to ride single file within the marked lanes on the edge of the Boulevard. However this is difficult because of the number of cyclists using the road and the need to move onto the road proper (the ‘car lane’) to overtake slower riders. The bicycle lane is also rough with lots of gravel washed off the cliffs on the non river side.

At the moment, motorists ‘own’ Yarra Boulevard and ‘suffer’ the presence of cyclists. What I’m proposing is a reversal of that onus – cyclists would be the natural ‘owners’ of Yarra Boulevard and drivers would be required to behave as their ‘guests’.

The proposal is simple and low cost. Only a few actions are required:

- Install prominent signage indicating that the full width of Yarra Boulevard is a shared bicycle/car route with drivers obliged to give way to cyclists

- Declare a 30 km/h maximum speed limit for cars

- Paint out the existing cycle lanes and tear up the Copenhagen lane that was built along part of the route

- Provide an initial period of visible enforcement with occasional follow ups thereafter

I’m not sure if there might be legal issues involved with the concept of a bicycle route where cyclists have priority but if there are they need to be addressed. That would be an institutional investment – it’s likely that there will be increasing demand for these sorts of road sharing arrangements in the future. Read the rest of this entry »

A bigger agenda for Bixis?

Posted: October 1, 2010 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: Bixi, Cycling, helmets, Melbourne Bicycle Share, safety 16 Comments While Melbourne Bike Share is struggling for riders, it isn’t struggling for attention.

While Melbourne Bike Share is struggling for riders, it isn’t struggling for attention.

I’ve been amazed at how the fate of the Bixis and reform of the compulsory helmet laws have been brought together and propelled into the public domain as a major public issue.

Before the Bixis, most people thought those who opposed mandatory helmets were the sorts of libertarian nutters who campaigned against obligatory seat belts and corresponded daily with the Unabomber. Now it’s widely recognised there’s a sensible countervailing argument.

There is clearly a power in the idea of Bixis. Melburnites won’t ride them but they like the idea of them.

Perhaps I’m over-reaching here, but I’m thinking that if a few blue bikes can do this with helmets, then they might be turned to a more powerful purpose, like promoting the legitimacy of all bicycles on Melbourne’s streets.

I don’t know if it’s their aspirational Parisian style or the fact that they’re an “official” government program, but the special appeal of Bixis could help to legitimise cyclists as valid road users in the eyes of drivers. Read the rest of this entry »

Should bicycles be registered?

Posted: September 22, 2010 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: bicycle, charging, Cycling, licensing, registration, taxes, VECCI 10 Comments The Victorian Employer’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VECCI) reckons bicycles should be registered and cyclists licensed.

The Victorian Employer’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VECCI) reckons bicycles should be registered and cyclists licensed.

VECCI’s recently released Infrastructure and Liveability policy paper, which is intended to influence public debate in the lead up to this year’s state election, argues that “road users should be treated equally. For example, all road users, including cyclists, should be licensed and vehicles registered”.

There are four key arguments commonly advanced against compulsory registration.

The first is that registration, as it is traditionally understood, is a charge for road damage, which rises exponentially with axle load. Since bicycles are extremely light compared to cars and trucks, the amount of damage they do is inconsequential.

The second is that fees for compulsory third party personal insurance are collected as part of the registration process. Again, bicycles are so light that the likelihood of cyclists seriously injuring other road users is very low (although they might injure themselves).

The third argument is that the scope for “incentivising” cyclists to obey the road rules via registration is limited. The main offence committed by motorists – speeding – doesn’t apply to most cyclists. They don’t avoid tolls because they’re not permitted on freeways and they don’t do a runner at petrol stations. Some might get picked up running red lights but not enough to justify the administrative cost of registration or the inconvenience of arming bicycles with legible number plates.

Finally, it is contended that cyclists impose very low, even zero, costs on the environment compared to motorised vehicles. Accordingly, they should be exempted from registration charges. Read the rest of this entry »

Melbourne Bicycle Share – how about some balance?

Posted: August 19, 2010 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: Bixi, Cycling, Dublin, Melbourne Bicycle Share, Montreal, The Age 11 Comments No, I don’t agree with Alan Todd of Kyneton that Melbourne Bicycle Share is a winner and I’ve never thought it would be (see my previous posts here, here and here).

No, I don’t agree with Alan Todd of Kyneton that Melbourne Bicycle Share is a winner and I’ve never thought it would be (see my previous posts here, here and here).

His letter to The Age this morning (“Share the smarts”) contends that bike share schemes have taken off in more than 135 cities around the world. “In any city that values public health, combined with a sustainable solution to transport and congestion problems, they would have to be a winner”, he says.

He also wants to see the compulsory helmet laws repealed so that Melbourne Bicycle Share can flourish.

I think the discussion around the Bixis is very confused. Too many people are mistaking policy on Bixis for policy on cycling. They’re very different – one’s a political stunt, the others real life.

Contrary to Mr Todd’s claim, Bixis won’t do anything whatsoever to reduce congestion even if their numbers are expanded. They are a substitute for walking and public transport in the CBD and near-CBD, not for cars. The sort of person who’s going to cycle at lunch time from Spring St to Melbourne Uni is not generally the sort of person who would otherwise drive. Read the rest of this entry »

Is Melbourne Bicycle Share getting better?

Posted: July 7, 2010 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: Bixi, Melbourne Bicycle Share, Montreal, RACV 8 CommentsNow that Le Tour has started, it’s timely to think about cycling.

And yes, Melbourne Bike Share is getting better (sort of). RACV announced back on 21 June that Melbourne is getting more blue Bixis “with 40 bike stations and 500 bikes commencing roll out this week”.

That clearly reads as additional to the existing ten stations and 100 bikes, and so should give us the full 50 bike stations and 600 bikes that were originally announced.

The new stations are located at New Quay, Bourke Street, Merchant St, Yarra’s Edge, along Elizabeth Street, the Rialto Tower, Southern Cross and Parliament Stations, Lygon Street and the Eye and Ear Hospital. Unfortunately the RACV doesn’t provide a time frame for the roll out but the Melbourne Bike Share map indicates that more than 30 stations are now up and running.

That’s good news, but there’s an alarming piece of information in the press release – the 100 bikes that launched the scheme were rented only 700 times (by 400 renters) in the initial three weeks between 1 June and 21 June. Read the rest of this entry »

Cycling and walking on the rise in US

Posted: July 4, 2010 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: biking, Cycling, GOOD, Ray LaHood, US Department of Transportation, walking Leave a commentThis graphic is from GOOD and is titled The Rise of Walking and Biking (click to enlarge). The supporting text says “You may be seeing more people out on the street walking and biking. But it’s not just because the weather is nice. There are more people walking and biking year round, and the Department of Transportation is responding by dramatically increasing the amount of money spent on projects for pedestrians and cyclists”.

The increase in walking and cycling has comfortably out-paced population growth. Nevertheless, the ‘headline’ message is the increase in expenditure by the US Department of Transportation on sustainable forms of travel – it has risen much faster than either walking or cycling (from $6 million in 1990 to $1.2 billion in 2009), particularly since President Obama appointed former Republican House of Reps Member, Ray LaHood, to the position of Secretary of Transportation.

$1.2 billion looks good, but bear in mind that President Obama’s budget request for FY 2010 is over $3.5 trillion.

Melbourne Bike Share – how can the Government save face?

Posted: June 8, 2010 Filed under: Cycling, Public transport | Tags: Bixi, helmet, Melbourne Bicycle Share, RACV, tourism 10 CommentsThere is a near universal consensus that Melbourne Bicycle Share is misconceived and almost certain to fail. Most attention has focussed on the compulsory helmet requirement but as I noted last week, this is a program that addresses a need that doesn’t exist and is designed in a way that will almost guarantee failure.

But no one wants a fiasco. The Government wants to save face, the RACV wants to keep its management contract and no one wants to see Melbourne’s reputation damaged by the failure of the blue Bixis.

So, I propose some radical surgery for Melbourne Bicycle Share.

First, forget about targeting the scheme at CBD workers running short errands. Reposition it instead as a service to promote tourism. The tariff should be turned around completely to support longer hire periods. For example, something more tourist-friendly, like $20 for the first two hours and $5/hr thereafter – hence $30 for 4 hours – would be close to the mark, although the tariff should be set with the goal of operating on a commercial basis.

Second, the Government should change the law to give anyone who can produce a valid out-of-State ID the right to ride a blue bike without a helmet. The exemption would not apply to any other bicycles and would be justified on the basis of supporting tourism. Tourism has been used to support Sunday trading in the dark and distant past when shopping on the Sabbath was a sin, so it’s an old and much used workhorse. Read the rest of this entry »