Do cities have a distinctive ethos?

Posted: December 20, 2011 Filed under: Miscellaneous, Planning | Tags: Avner De-Shallit, Daniel A Bell, Grattan Institute, Jane-Frances Kelly, Karratha, Oxford, The spirit of cities 12 CommentsCity managers love a catchy idea. Ten years ago it was “creative cities”; next it could be the idea that cities should discover their own “ethos” to protect them from the homogenisation of globalisation.

Avner De-Shallit and Daniel A Bell have just published a new book, The spirit of cities: why the identity of a city matters in a global age, which they say revives the classical idea that a city expresses its own distinctive ethos separate from its national affiliation. They take their definition of ethos from the Oxford dictionary: “Ethos is defined as the characteristic spirit, the prevalent tone of sentiment, of a people or community”.

The authors look at nine cities which, they argue, each have a dominant ethos. The cities are Jerusalem (religion), Montreal (language), Singapore (nation building), Hong Kong (materialism), Beijing (political power), Oxford (learning), Berlin (tolerance and intolerance), Paris (romance), and New York (ambition). According to the publisher’s blurb:

Bell and De-Shalit draw upon the richly varied histories of each city, as well as novels, poems, biographies, tourist guides, architectural landmarks, and the authors’ own personal reflections and insights. They show how the ethos of each city is expressed in political, cultural, and economic life, and also how pride in a city’s ethos can oppose the homogenizing tendencies of globalization and curb the excesses of nationalism.

You can get a sense of what the whole idea is about from this transcript of a public seminar on The Spirit of Cities the Grattan Institute conducted with Professor Bell on 4 October 2011. You can also read the first chapter of the book, titled Civicism, and some of the chapter on Jerusalem, at Amazon (use the ‘look inside’ option). Chapter one is instructive because it sets out the rationale, theory and methodology, with subsequent chapters discussing each city in turn.

It’s an interesting idea, but I remain to be convinced. For starters, separating national from city-level characteristics is a minefield. As if to reinforce this difficulty, De-Shallit and Bell mess it up from the outset. They select Singapore as one of their examples even though it’s a city-state. Arguably, Hong Kong was too up until relatively recently.

And what, in practical terms, do we settle on as a city’s intrinsic ethos? I don’t find the discovery that Jerusalem is a city of religion, or that diminutive Oxford (population 165,000) is a city of education, provides any greater insight into these places than the discovery Karratha is a mining town. All that tells me is these are their dominant industries – that’s not telling me about the spirit of the place.

And if Bejing’s ethos is political power, that’s also true of most of the many other places that specialise in government, like Washington DC and Canberra (and there are many of them – for example, 33 capital cities in the US are not the most populous city in their State. Olympia, the capital of Washington State, has a population of just 50,000). Perhaps the hand of politics feels heavier to the outside observer in Beijing, but if so, that could be because of a national-level characteristic – it’s a communist state – rather than a city-level one.

It’s also very hard to separate out what’s city branding/marketing and what is the characteristic spirit of a place, or the collective aspirations and beliefs of its residents. New York is certainly a world power in finance and media and has marketed itself accordingly. But does “ambition” permeate the lives of all those New Yorkers – the great bulk of the city’s population – who aren’t “Masters of the Universe” e.g. the teachers, doctors, suburbanites, shop assistants, retirees, truck drivers, stay-at-home parents, people living in “the projects”? I don’t think so.

Similarly, does “romance” permeate all walks of life of Parisians or is it something projected onto the place by visitors (and maybe helped along with some savvy Gallic marketing)? Read the rest of this entry »

How much housing can brownfields sites supply?

Posted: December 6, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: brownfield, Housing, industrial, redevelopment, zoning 9 Comments

Examples of former industrial zoned sites now currently zoned residential. Images in clockwise order: Cardinia, Mornington Peninsula, Maribyrnong and Kingston (graphic from DPCD)

Governments like to point to disused industrial sites as a significant source of land for expanding housing supply within the established suburbs. Only recently, for example, the Victorian Government talked up the potential of Melbourne’s Fishermans Bend as a new “Growth Corridor”.

So-called brownfields sites can make a useful contribution to housing supply but the available evidence suggests their potential is over-stated. One of the risks of taking too-optimistic a view of brownfields is that the formidable obstacles to other sources of supply – like higher density housing in activity centres and infill developments – will tend to be neglected.

The potential of brownfields sites is limited by a number of factors. They might be in locations that are unattractive to the market (e.g. deep within an industrial area) or are expensive to service. Some have been contaminated by industrial processes and it’s possible another use might be preferred over housing.

Challenge Melbourne, the discussion paper prepared to kick-off the Melbourne 2030 process, estimated brownfields sites could contribute 65,000 dwellings over the period 2001 to 2030. While useful, this was well short of the estimated number of new dwellings that need to be constructed – for example, the latest edition of Victoria in Future projects the number of households in Melbourne will grow by 825,000 between 2006 and 2036.

Now the Planning Department has produced a new study which throws further light on the likely contribution brownfields sites could make to housing supply in Melbourne.

The department estimates more than 400 ha of industrial land was rezoned from industrial to residential in Melbourne over the last ten years. The exhibit shows new housing constructed on former industrial sites in Cardinia, Mornington Peninsula, Maribyrnong and Kingston.

That’s an average of 40 hectares each year over the last ten years. If each hectare was developed at a net density (say) of 20 dwellings, that would mean brownfields sites have contributed on average 800 dwellings p.a. to Melbourne’s housing task.

Compared to Victoria in Future’s projection that the number of households in Melbourne will grow by an average of 27,500 p.a. between 2006 and 2036, that 800 dwellings p.a. seems a decidedly modest contribution. In fact, it’s not certain that rezoning always leads to development and, where it does, what proportion of the site is used for housing. Many of the lots identified by the Department are in suburban locations so even my assumed net density of 20 dwellings per ha might be optimistic.

There are of course other non-industrial sites that could potentially be used for housing. For example, a major housing development was proposed for the former Coburg High School site in Bell St (although it appears to have fallen over). The trouble is there are likely to be many fewer such sites available than industrial sites. I’m not in any case aware of an estimate of their likely supply potential and the associated timing.

I applaud DPCD for producing this new study. There are still many questions around the supply potential of brownfields and other major sites, so I would like to see the department continue with this work. As it stands, the existing evidence suggests the Government should be very wary about over-selling the contribution brownfields can make to housing supply in Melbourne.

______________________________________

Book giveaway: follow this link to be in the running for one of two copies of Jarrett’s Walker’s new book, Human Transit

Are we squandering infill housing opportunities?

Posted: December 5, 2011 Filed under: Housing, Planning | Tags: Alphington, councils, density, dual occupancy, infill, medium density housing, third party appeals 29 CommentsI’ve argued before (here, here and here) that new housing supply within Melbourne’s established suburbs is excessively dependent on small-scale infill housing projects. In the expansive middle ring suburbs, around half of all housing projects provide only one or two additional dwellings, with the great majority providing only one.

It’s therefore important to look at other options, but given it’s carrying most of the burden, it’s also worth asking if infill is being managed as efficiently as it could be.

The exhibit above shows a newly completed infill development at 2-4 Old Heidelberg Rd in suburban Alphington (here are some interior pictures). It provides eight dwellings on an 825 sq m site that originally would’ve been intended to accommodate a single detached house like its neighbour.

That’s a big up-lift in density – if most infill projects yielded this many new dwellings we wouldn’t have a supply problem. But the great bulk are simple dual occupancy developments. This raises the important issue of whether we’re maximising the value we’re getting from the limited supply of precious infill sites.

If projects that could yield four, six or eight new units are only providing one, then that could represent a very high opportunity cost. Given that activity centres in the middle ring suburbs are mostly failing to deliver much new housing, what we ideally want to see is each lot delivering to its full potential – yielding the maximum number of new dwellings that, having regard to its particular circumstances, it reasonably could.

There are of course many “objective” reasons why not all projects can yield as many dwellings as 2-4 Old Heidelberg Rd. Some redevelopment sites are small or inconveniently shaped. Some may have infrastructure inadequacies or access might be hard.

There are also a range of legitimate planning constraints like heritage, over-looking and solar access that might limit the number of units that can be built on a given lot. And the nature of the market in a particular area could mean the highest return comes from building fewer dwellings rather than maximising the total number.

But there are reasons to suspect that “objective” factors do not always, or even usually, explain why a lot isn’t developed to its potential. Consider these two contiguous lots in Elphin St Ivanhoe – although they’re the same size and have a common context, one has six dwellings and the other has two.

The most commonly cited explanation for these sorts of anomalies is the “dead hand” of the planning system. Additional cost and risk is imposed on projects by self-interested opposition from existing residents. Councils often lack the resources and skills to deal with the complexity of sophisticated opposition and, not surprisingly, often take a position more sympathetic to their constituents than to the developer.

There’s a range of measures that have been suggested to tilt the balance more toward redevelopment. These include abolition of third party appeals (the issue got a run in The Age recently), code-based approval systems, more resources for councils, better forward planning, and so on. I endorse this position but there’s no doubt it’s very hard politically, both for councils and the state government.

I think there’s another approach that’s worth thinking about, particularly for the middle ring suburbs. We know infill developers tend to be small and it could be that many simply lack the knowledge, skills, access to finance and appetite for risk to enable them to undertake larger projects. They might not have the wherewithal to push for larger projects in the face of vigorous opposition from neighbours and limited support from timid councils.

Perhaps the project class with the greatest potential for “under-utilisation” is dual occupancy. Landowners carve off a bit of land and sell it, usually for the construction of one additional dwelling. That way they get to stay in their old house and transform some excess land into cash without taking much risk.

That’s a net addition to supply so it’s positive. While in many cases the value of the existing dwelling will preclude more intense development, dual occupancy is a lost opportunity if the entire site could’ve been successfully redeveloped for four, six or eight dwellings. Read the rest of this entry »

Are these really the most (and least) liveable suburbs in Melbourne?

Posted: November 27, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: Hallam, index, Liveability, Our Liveable City, South Yarra, suburb, The Age, Tract 10 CommentsI never read those glossy magazine inserts in The Age (who does?) but on Friday I made an exception for The Melbourne Magazine because it promised to tell me “the most liveable suburb in the world’s most liveable city”.

The Age’s Our liveable city project ranks the “liveability” of 314 suburbs from top to bottom and claims to reveal “Melbourne’s best suburbs, the ones improving the most, and where you should buy your next home”.

Liveability is defined initially as “the general quality of a place that makes it pleasant or agreeable for people to reside in”. Fortunately, someone saw that was a tautology and wouldn’t be of any practical help. So liveability is subsequently defined by 13 measurable criteria.

These cover topography, traffic, crime, cultural facilities and parks, as well as proximity to a range of amenities – the CBD, beaches, public transport, schools, restaurants and shops. Scores out of five on each criterion are added to give an overall summary score for each suburb. Each suburb is subsequently ranked from 1 to 314 on an Index of Liveability.

Unsurprisingly with this sort of exercise, there was a lot of criticism from readers, with many pointing to apparent anomalies in the rankings. One said, “once I saw Footscray was rated higher than Middle Park I stopped reading”.

Disagreement is inevitable. People are different and so it’s hard to get consensus on just what does, or doesn’t, make a place liveable. That shouldn’t be surprising – an elderly couple, for example, is likely to have a very different definition of liveability to that of a young single. Throw in further differences, say in education, income or ethnicity, and it gets much more complex.

There is a much more straightforward and reliable way of establishing the relative liveability of suburbs. That simply involves measuring what people are prepared to pay to live in them i.e. property prices. It doesn’t require complex measures and weights (not that The Age bothered with the latter). In fact it sidesteps entirely the hardest and most intractable question of all – defining apriori just what liveability is.

Moreover, it provides a clear ranking and allows us to measure the size of the difference between suburbs. And it’s based on the actual decisions of hundreds of thousands of householders. Knowing that the average property value in South Yarra is three and a half times higher than in Hallam is a much more useful and valuable piece of information about the relative merits of the two suburbs than knowing one ranks 350 places ahead of the other on the Index of Liveability.

There’re distortions in the market so property values aren’t a perfect representation of the relative liveability of Melbourne’s suburbs. I would argue however that this approach involves infinitely fewer compromises than the methodology used by The Age. Of course it wouldn’t make a very interesting story when there’s the option available to the newspaper of bringing some “science” to the issue.

That’s not to say exercises like the Index of Liveability don’t have value. They can be useful to establish just why residents think one suburb is more liveable than another. Knowing why properties average $1,300,000 in South Yarra and $369,000 in Hallam would be very important information for policy-makers.

Interpreted this way, I think The Age’s attempt is actually better than many of the commenters are prepared to concede (even though I’m annoyed that very little information about the methodology is disclosed). You can argue the toss at the margin – for example, I suspect proximity to schools only matters in the case of certain institutions – but by and large the criteria are a reasonable compromise. Read the rest of this entry »

Could major housing developments be outside activity centres?

Posted: November 23, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: activity centre, infill housing, medium density, retrofit 16 Comments We need to start thinking about new ways of increasing housing supply in the established suburbs. As I’ve noted a number of times now, activity centres aren’t delivering much and infill housing, though it’s putting in a sterling effort, is probably at full stretch. These strategies are still important, but additional sources of supply are needed.

We need to start thinking about new ways of increasing housing supply in the established suburbs. As I’ve noted a number of times now, activity centres aren’t delivering much and infill housing, though it’s putting in a sterling effort, is probably at full stretch. These strategies are still important, but additional sources of supply are needed.

Much of the current thinking confines major developments to a narrow range of locations, primarily activity centres and major transport corridors where key infrastructure, particularly rail lines, already exists. Many have argued these locations have the potential to accommodate enough apartments to house all of Melbourne’s projected growth for decades to come. I don’t doubt they could in theory, but in reality they’re not doing enough.

I think there are lessons we can learn from the study of infill housing I discussed last time. One is the decisive importance of land – developers working at all scales need to be able to easily acquire or assemble sites that are of an appropriate size and aren’t encumbered by high-value improvements.

Developers don’t want to be rejected or delayed by unhappy neighbours or sent packing by councils that impose restrictive limits and conditions on development. And they need to offer housing types that are attractive to the market in that locality – not everyone who’d be inclined to live in the middle ring suburbs would want to live in an apartment.

I think there’s another option worth investigating that addresses many of these concerns. Although it’s just an idea at the moment, it involves a reverse strategy – encouraging residential and commercial development in areas that usually have poor infrastructure, but large sites and compliant neighbours. Rather than require infrastructure to be in place first, it involves retrofitting infrastructure like public transport in order to create new living areas.

It relies on the existence of sites in the suburbs which are large, in single or limited ownership, have few neighbours, and are either undeveloped or have relatively low-value improvements such as warehouses. Some sites that meet these criteria are attached to large public sector organisations like tertiary institutions and utilities, but are surplus to requirements.

As an example, I’m familiar with a tertiary institution in an Australian capital city that’s located within 20 km of the CBD and has more than 100 ha of surplus developable land (that’s five times the size of Melbourne’s E-Gate). It is in a single ownership and already has the extensive infrastructure and services required to serve a student population and workforce of many thousands.

It’s in an attractive environment and could potentially be redeveloped as a major regional activity centre at relatively high densities. It isn’t near a train line, but is well-connected by buses to the rail network with the potential to add more to suit the needs of a very large permanent resident population. I’m aware professionally of some opportunities in Melbourne that are consistent with this example.

However most of the prospective sites are likely to be used at present for storage, distribution and manufacturing activities. They’re not brownfields sites though, because they’re not disused. The idea is that rezoning would provide owners with an incentive to redevelop their properties for intensive residential and commercial uses.

The extended area running through Clayton/Monash/Glen Waverley is a possible candidate in Melbourne. It has a number of large industrial sites that could potentially be redeveloped given an appropriate inducement. This region is particularly important because it already has the largest concentration of jobs in suburban Melbourne (albeit at relatively low density compared to the CBD) and is a prime candidate for development as a Central Activities Area.

While it isn’t well-served by rail, it could potentially be retrofitted as part of the proposed Rowville rail project. More plausibly, it could be serviced at a lower up-front cost by an expanded bus rapid transit system similar to that now connecting Monash University with Glen Huntley Huntingdale station.

The overall idea of retrofitting relies on the sheer size and intensity of projects to provide the incentive for redevelopment and to justify investment in infrastructure. The scale of projects would also be a key way of differentiating developments from neighbouring uses, some of which may retain their non-residential character, at least in the short term. Read the rest of this entry »

Can Melbourne depend on infill housing?

Posted: November 22, 2011 Filed under: Housing, Planning | Tags: activity centre, City of Monash, Housing, infill, Jim Petersen, medium density, Monash University, Rail station, Shobit Chandra, Thu Phan 13 Comments

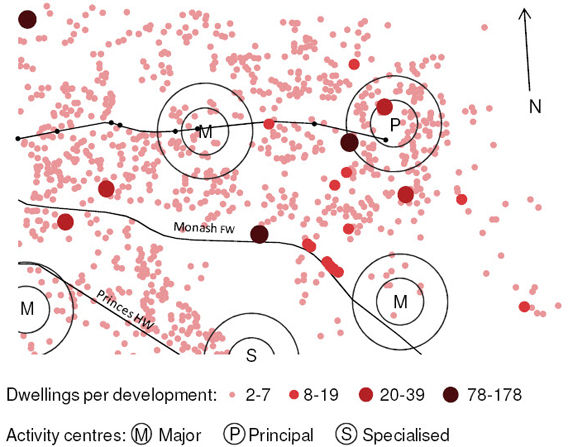

Geography of infill developments in City of Monash, 2000-2006 (source: Phan et al, 2008 - graphic via Grattan Institute)

We know that the inability to increase significantly the supply of dwellings within established suburbs is a key failing of strategic planning in Melbourne. Simply put, there’s not enough housing to make established suburbs affordable for all the people who would like to live in a relatively accessible location.

We also know that activity centres aren’t pulling their weight in the task of increasing supply (see here and here) and that the burden of supply is instead falling on small-scale infill development, much of it dual occupancy projects. So it’s worth looking further at the nature of infill housing.

A study by Monash University’s Thu Phan, Jim Peterson and Shobhit Chandra , Urban infill: the extent and implications in the City of Monash, examined new developments in the municipality over the period 2000-06. They defined infill primarily as projects where two or more new dwellings were constructed on sites formerly occupied by detached houses. A total of 1,483 projects were identified, ranging in size from two dwellings to 178.

The study revealed a number of interesting aspects about this middle suburban municipality.

First, it found new dwelling supply is dominated by small projects. One project built more than 178 dwellings and three built between 40-77 dwellings, however 98% of projects involve just 2-7 seven dwellings (and we can be pretty confident they’re heavily weighted toward the smaller end).

Second, projects are dispersed, not concentrated. As shown in the exhibit, proximity to major trip generators is uncorrelated with location of projects. Just 5% are within 400 metres of a Principal, Major or Specialised activity centre, and only 10% are within 400 metres of a rail station. Moreover, the authors found projects located within 400 metres of an activity centre are smaller on average than those in more distant locations.

Third, developers tend to be opportunistic rather than strategic – they wait for properties to be offered for sale and assess each one on its potential for redevelopment. Thus the geography of infill development is shaped largely by what comes on the market rather than by any sort of deterministic planning policy.

Fourth, the size of lots and the age of the existing house is a more important influence on the location of infill development than proximity to an activity centre or rail station. The average infill site is relatively large (700 to 900 sq m) and the majority of existing dwellings are relatively old i.e. built between 1945 and 1965. Lot sizes close to rail stations are smaller – and hence less amenable to redevelopment – than those further away, probably reflecting the different periods of development.

Thus not only are activity centres failing to expand housing supply in accordance with the precepts of Melbourne 2030, but the great bulk of new housing being built in Monash isn’t located close to activity centres but rather is dispersed (relatively uniformly too judging by the exhibit i.e. non-randomly).The dispersed pattern will worry some, but I don’t see it as a big issue. Read the rest of this entry »

What’s happened to the idea of the compact city?

Posted: November 21, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: Activity centres, compact development, DPCD, Housing Development Data 2004-2008, Melbourne 2030, Melbourne @ 5 Million, smart growth, urban consolidation 3 CommentsPending completion of the Government’s new urban strategy for Melbourne, the two major strategic planning documents that jointly guide the metropolitan area’s development – Melbourne 2030 and Melbourne @ 5 Million – are rich with rhetoric about the importance of directing development to established suburbs rather than the periphery. They also emphasise the desirability of concentrating that development around activity centres instead of dispersing it throughout the existing suburbs.

In a show of great political courage, Melbourne 2030 sought to limit the share of Melbourne’s population growth in peripheral Greenfield developments to just 38%. Virtually all the rest would be located within the established suburbs, of which 40% would be concentrated in activity centres.

However the supplementary strategy released six years later in 2008, Melbourne @ 5 Million, relaxed the target considerably. It was clever – it slackened the numerical target to 47% while simultaneously narrowing its geographical ambit to just the six Growth Area municipalities. These six cover an area much smaller than that implied by the term ‘greenfield’ used in Melbourne 2030.

This statistical report prepared by the Department of Planning and Community Development (DPCD), Housing Development Data 2004-2008, reveals that the new Melbourne @ 5 Million target wasn’t very demanding. It merely echoed the way the market had behaved over the preceding four years.

Over 2004-08, the Growth Area municipalities accounted for 44% of net new dwelling construction (after subtracting demolitions). Once the larger average household size of outer suburban households is taken into account, this is much the same as Melbourne @ 5 Million’s 47% population “target”. Rather than seek to change the market as its rhetoric suggests, Melbourne @ 5 Million was essentially business as usual.

In any event limiting the target to Growth Areas could be construed as misleading. They are not the same as the outer suburbs. There was considerable growth in other peripheral municipalities over 2004-08 e.g. Frankston, Nillumbik, Mornington Peninsula and Yarra Ranges. When they are added to the Growth Area municipalities, the outer suburbs accounted for 54% of all new dwelling construction in the metropolitan area over 2004-08. In terms of the share of population growth, the number would be somewhat higher.

So Melbourne @ 5 Million essentially had no real ambition to drive significantly higher housing supply in the established suburbs. Despite what the text sought to imply, it settled for them absorbing just 46% of new dwellings.

Melbourne @ 5 Million also dropped any numerical targets for activity centres. Previously, Melbourne 2030 projected that 40% of the population growth within the established suburbs would be concentrated at relatively high densities, with the other 60% in small infill developments dispersed across the suburbs. Read the rest of this entry »

Would Seaside work in outer suburban Melbourne?

Posted: September 26, 2011 Filed under: Housing, Planning | Tags: Florida, new urbanism, Seaside, The Truman Show 13 CommentsWhen I first saw pictures of Seaside many years ago, I imagined that’s what the outer suburbs of Melbourne could look like one day. Click on the picture and go for a “walk” around the Florida village that had a key role in inspiring the New Urbanism movement. Seaside is famous – you might know it from its role in The Truman Show or from its distinctive array of “story book” houses.

Although the houses are detached, you’ll see many of the key ideas of New Urbanism in Seaside, including houses that open up to neighbourly streets and paths, have no garages and are within an easy walk of the town centre. Keep an eye out for walking paths. Given the kind of detached housing that’s being built today in Australian cities, I find it extraordinary that the first stage of Seaside was started 30 years ago!

It doesn’t push all the New Urbanism buttons. For example, the range of dwelling types is pretty limited and there’s not much evidence of transit orientation (it’s not a commuter village). Nevertheless, average density approaches the aspirational 25 dwellings per hectare, well in excess of the 15 dwellings per hectare promoted in Melbourne 2030 and in new fringe structure plans like the one for Toolern, near Melton.

For my money, the key reason Seaside has such broad popular appeal is the two and three storey detached “Hansel and Gretel” houses, with their faux widow’s walks and sometimes extravagant follies. Some architects however find it twee – they wince at the sentimentality and overwrought quaintness of the place.

I think it also appeals because of the determination of the architects to eliminate garages. This enables living areas to be placed at the front within a conversation’s distance of the sidewalk. It captures a half-forgotten notion of neighbourliness and conjures romantic images like promenading.

This contrasts with the practice in Melbourne where both new suburban houses and traditional inner city terraces tend to put bedrooms at the front and the main living areas at the rear (only apartments and older suburban houses seem to have living areas facing the street, although they’re usually set way back from the front boundary).

A parallel with Melbourne though is the limited area of private open space. I hear frequent condemnation of big houses with small yards in Melbourne’s outer suburbs (as if buyers can’t make their own decisions about what size yard they want!) but the area of private open space in Seaside looks positively miniscule. As with apartment dwellers, I’d expect the quality of the public realm is an important offset.

As a possible model for Australian suburbia, it’s important to get Seaside in context. It’s not a big place – it only covers about 50 32 hectares (the part of Fishermans Bend mooted for redevelopment is 200 Ha) and has around 500 houses. (Update: the whole area though, including very similar contiguous developments, is about 100 Ha with 1,000 or more houses – see Comments). Also, it’s essentially a beachside resort for people who are well-off. Many of the houses are rented to holiday makers and in that sense it functions more like the swank residential areas close to Hastings Street in Noosa than the suburbs of Melbourne or Sydney.

Like Noosa, it’s a long way from the nearest major urban centre. Dwellings are architect-designed and costly to build – properties at Seaside have sold for as much as $5 million (presumably ones on the beachfront). Further, I suspect a major reason there are so few cars in the streets is that holiday makers fly in and have no need to drive in what is essentially a self-contained resort. The town centre seems improbably built-up for 500 dwellings and that could be because this is a tourist town, drawing visitors from well beyond Seaside’s border.

I can imagine something like Seaside working on old brownfield sites in Melbourne like Fishermans Bend and E-Gate, but what would happen if it were transplanted to the suburban fringe? Read the rest of this entry »

Are cul-de-sacs a dead end?

Posted: September 22, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: cul de sac, new urbanism, permeability, Toolern, walkability, Wesley Marshall 8 CommentsThe New Urbanism hates cul-de-sacs – they’re emblematic of much that’s wrong with car-oriented suburban cities, including poor walkability, low transit provision, long travel distances, “excessive” demand for privacy, and even low social capital.

I might be in a minority, but I’m an admirer of cul-de-sacs. They’ve been around for thousands of years for good reason. I grew up in what in my day was called a “dead end”, 6 km from the city centre. I lived in a terraced mews in Sydney for six years, just 1 km from the Town Hall. I now live in a seven property cul-de-sac developed in the 1950s, 8 km from Melbourne town hall.

The great advantage of cul-de-sacs is they have no through traffic, so they’re quieter and it’s safer for children to play outside on the street. As long as they’re not too long, they can create a sense of place and possibly promote greater social interaction among residents too (although it’s not clear how much of that’s due to the cul-de-sac form; to lower traffic levels; or in some cases to joint ownership of common property). It’s also a matter of no little importance that residents seem to like them.

Another claim is cul-de-sacs reduce infrastructure costs significantly compared to a grid plan. Further, they “allow greater flexibility than the common grid in adapting to the natural grades of a site and to its ecologically sensitive features, such as streams, creeks and mature forest growth”.

Cul-de-sacs are popularly associated with outer suburban developments and that’s why they get such a bad rap. However they can work in a range of urban contexts. They’ve often been used in inner city traffic calming schemes (where they’re called “street closures”). Large, higher density redevelopment projects like this one in Brisbane use what is essentially the cul-de-sac form to give access to dwellings without a street frontage. Yarra Bank Court in Abbotsford would be better with pedestrian access for residents at the far end but is otherwise a delightful “dead end”.

According to critics, the key disadvantage of suburban cul de sacs is they create a circuitous road system, necessitating longer travelling distances. This discourages walking and increases the cost of providing public transport when compared to a traditional grid pattern.

It’s true that many older suburban estates are relatively impermeable. However as inner city street closures show, it is quite easy to design cul-de-sacs that are open for pedestrians but not cars. It’s also quite simple to have a 1 or 1.5 km rectilinear grid of main roads for buses (e.g. see Toolern) with cul-de-sacs confined to “filling in” each square.

I think the main reason cul-de-sacs are demonised by new urbanists is because they’re conflated with the problems of outer suburban development. Consider this quote from Wesley Marshall, an assistant professor of civil engineering at the University of Colorado:

A lot of people feel that they want to live in a cul-de-sac, they feel like it’s a safer place to be. The reality is yes, you’re safer – if you never leave your cul-de-sac. But if you actually move around town like a normal person, your town as a whole is much more dangerous.

Professor Marshall says fatal accident rates are lower in areas with a traditional grid pattern, but he makes an elementary mistake. The traditional areas are older – they don’t have fewer fatal accidents because of their street morphology but because they’re denser, with more mixed development, more traffic and slower travel speeds than outer suburban areas. The primary “culprit” here isn’t the cul-de-sac, it’s the lower density and monoculture of the newer suburbs.

The same article says “people who live in more sparse, tree-like communities drive about 18 percent more than people who live in dense grids”. Again, that’s primarily because of differences in density. For example, destinations are further apart in outer suburbs so residents are less likely to walk or cycle. Given the article refers to the US experience, it’s possible, even likely, that differences in income between the two areas are an important explanatory factor too. At least this time the writer talks about “sparse” communities rather than specifically fingering cul-de-sacs. Read the rest of this entry »

Why do outer suburban streets look so bland?

Posted: September 18, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: Bass Coast Shire Council, development, Housing, Matthew Guy, mcmansion, streetscape, Ventnor Phillip Island 10 CommentsCritics are gunning for Victoria’s Planning Minister, Matthew Guy, following his decision to rezone 5.7 Ha of farmland at Ventnor, Phillip Island, for residential use despite the opposition of Bass Coast Shire Council. The rights and wrongs of the Minister’s decision is no doubt a fascinating topic, however my present interest is in the way this land is likely to be developed.

I got to thinking about that after reading a letter in the paper on Saturday from the owner of a beach house at Ventnor, expressing the “hope that this natural wonderland does not become transformed into a home of little courts, high fences, and narrow streets filled with the McMansions of suburbia”.

I wouldn’t be holding my breath if I were him – there’s got to be a much better than even chance that any new residential development will end up looking more like nearby Manna Gum Drive (see exhibit) than the more traditional ‘beach houses’ of Ventnor. In fact even that seems optimistic – given the enormous decline in average lot sizes in recent years, a more probable scenario could be this development in Melton.

He can probably rest easy about his fear of McMansions though. Two storey behemoths are likely to be too expensive for most Ventnor newcomers – it’ll probably be single storey brick veneers with low tile roofs and two car garages.

Being near the beach doesn’t faze the standard suburban form – it’s ubiquitous. Drive 100 metres back from the beach in large parts of the sub-tropical Sunshine Coast or Gold Coast, close your eyes, and you could as easily be in the bland streets of Melton or Campbelltown. You’ll even have the same experience in tropical Cairns.

I expect they all look much the same because the economics of land development and cottage building produces the same solution everywhere. Affordable lots are 500–700 sq metres with high fences for privacy. The houses look more or less the same because the home building industry is pretty efficient at churning out economically priced detached houses in low-maintenance brick veneer.

As with most mass produced items built to a price, the scope for differentiation isn’t high, often just a tweak of the front facade. Buyers can have something markedly different if they want – they might, for example, commission an architect – but they’ll have to pay a lot more for the advantages of a bespoke design. But that’s just not an option for the vast bulk of buyers in areas like Melton and, I daresay, Ventnor.

A key reason streets in fringe suburbs look so boring and nondescript to sophisticated eyes is their relative youth – trees planted in the nature strip haven’t had time to take off and residents haven’t yet established front gardens. Many streets in established suburbs were bland once too. The streets of Eaglemont and Ivanhoe doubtless looked pretty insipid at first with their small brick and tile houses, but generations of zealous gardeners cultivating their front yards and nature strips have created, in effect, a completely new streetscape.

Yet there are many streets in established suburbs like this one in Keysborough which are still pretty uninspiring despite the advantages of maturity. This relatively young street in Melton looks like it’s lost some street trees already and parts of the nature strip have become a parking lot. Here’s another newish one in Melton where the front yards don’t even pretend to be gardens – they’re all driveway and low maintenance ground cover. And most of the houses on this street on the Sunshine Coast were built at least 30 years ago (in fact some have been redeveloped) yet apart from a few desultory palms, trees with scale aren’t very common. Read the rest of this entry »

Is Melbourne pushing the boundary (too far)?

Posted: September 15, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: CSIRO, density, Geosciences Australia, image, La Nina, satellte, sprawl, suburbs, urban growth Leave a comment

Melbourne in 1988 - a part of the 2010 image, showing the effects of the drought, is visible on the RHS

Geosciences Australia has released a new series of satellite images comparing the extent of development in Melbourne in 1988 with 2010. Click on the image above to go to Geosciences Australia’s web site where you can do a “swipe” comparison of the two images i.e. move the cursor across the image to progressively reveal the second image underneath.

According to a report in The Age, the images show a “massive” increase in urban sprawl, with Melbourne’s urban footprint surging to the north, west and south-east. Melbourne has “marched into surrounding rural landscapes” and its “unofficial boundary is now more than 150 km east to west”.

Melbourne has certainly expanded at the fringe over the last 22 years, there’s no doubt about that. However I’ve argued before that both the extent of sprawl and its downsides are routinely exaggerated, so I want to have a closer look at these images and at The Age’s interpretation.

One thing that struck me straight up is that any comparison of the two satellite images can be misleading unless the viewer appreciates Melbourne was still suffering the effects of a long drought in 2010 (compare the size of the dams in each year). So areas that appear to have gone from green to brown between 1988 and 2010 might reflect lack of rain, rather than an increase in development.

In fact 1988 was an unusual year. There was a La Nina event in 1988-89 – the first since 1973-76 – and hence there were wetter than normal conditions. Have a look at this older CSIRO comparison of satellite images of Melbourne in 1972 and 1988, and note the CSIRO cautions that 1972 was much drier than 1988.

It should also be borne in mind that 22 years is a reasonably long period in urban development terms. We shouldn’t be surprised to see substantial change when a metropolitan area is growing. Have a look at these images to see how spectacularly some other growing cities have changed in the course of 20 years.

The level of growth also needs to be considered. Melbourne’s population grew from circa 3.1 million to around 4 million between 1988 and 2010. That’s an increase of about 30%, which is considerably more than the apparent increase in the size of the urbanised area. That’s to be expected, as a large proportion of population growth – currently approaching half – is accommodated within the existing urban fabric via redevelopment.

And then there’s The Age’s claim that Melbourne’s urban footprint spreads “more than 150 km east to west”. It doesn’t. Using GIS, I measure at most 75 km from the western edge of Wyndham to Lilydale in the east and 85 km to Pakenham in the south-east. If I measure instead from Melton (putting aside that it’s separated by 9 km of green wedge from the continuously urbanised area), I still get less than 80 km to Lilydale and less than 100 km to Pakenham. Some might think that’s still too big, but it’s a lot less than 150 km plus. Read the rest of this entry »

Does being the most liveable city in the world mean anything?

Posted: August 31, 2011 Filed under: Miscellaneous, Planning | Tags: Adelaide, Auckland, Cities of Opportunity, Economist Intelligence Unit, livability, Liveability Ranking Report August 2011, Mercer Quality of Living Survey, Perth, Pricewaterhousecoopers, survey, Sydney 4 CommentsThe good thing about ‘winning’ the World’s Most Liveable City gong is that it might help market Melbourne to overseas tourists, students, investors and maybe even buyers of our services. Unlike the Grand Prix, it costs us nothing. And while it won’t stop some Melburnians from pissing in trains (like this guy in case you missed him in yesterday’s post), it might give many others greater pride in their city. The thousands of Melburnians who travel overseas for business or pleasure each year can now be ambassadors for their city with this neat and handy marketing tool.

But of course league tables like The Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) annual Liveability Survey are all bunkum and sensible people shouldn’t be sucked in. The EIU’s Survey purportedly provides an objective ranking of world cities based on 58 variables measuring dimensions like political stability, health care, environment, culture, education and infrastructure. However, as I’ve explained before (here, here and here), there are a number of reasons why liveability league tables are best left to the marketeers.

The EIU’s Survey is designed primarily to assist companies with formulating appropriate living allowances for staff posted to overseas cities. These people are transitory and well-heeled – they don’t experience the city like the average permanent resident. They usually rent somewhere convenient and salubrious, so they won’t care too much about high housing prices and inadequacies in outer suburban public transport.

There are also difficult methodological problems involved in arriving at a single summary ranking of a city’s “liveability”. These sorts of surveys typically have lots of variables – some are easy to measure, others are very subjective. The analysts often make the convenient but unrealistic assumption that they’re all of equal value (weight). Not all of them can be ‘added’ together in any meaningful sense, yet they have to be to arrive at a simple league table.

The differences between top cities in these sorts of surveys are in any event miniscule and hence of little consequence. For example, the top five ranked cities in the EIU’s survey all scored 97 points out of 100 (see exhibit) – this would be swamped by the margin of error in the estimates. The EIU acknowledges that “some 63 cities (down to Santiago in Chile) are considered to be in the very top tier of liveability, where few problems are encountered…. Melbourne in first place and Santiago in 63rd place (can) both lay claim to being on an equal footing in terms of presenting few, if any, challenges to residents’ lifestyles”.

Defining “liveability” is itself a difficult challenge (I’ve discussed this before in the context of the ‘Sydney vs Melbourne’ debate – see here and here). The EIU finds the concept so slippery it comes up with this tautology: “The concept of liveability is simple: it assesses which locations around the world provide the best or the worst living conditions”. Arriving at a consensus definition is extremely hard because it depends on a number of factors, like the characteristics of the observer – for example, their ethnicity, their income, their stage in the life cycle and so on. The vibrant centre of Melbourne might add nothing to the city’s liveability for someone who’s elderly, or on a low income, or a member of a cultural group that is under-represented in the city.

It’s not surprising the EIU’s top ten cities seem to be all of a one. They’re all medium sized cities (no megalopolises here), they’re practically all low to middling density, they’re all in first world countries and, with the possible exception of Sydney, they all have cool to cold climates. What seems obvious is that the ranking is shaped much more by the characteristics of the host country than anything else. Factors like political stability, health and education – which loom large in the selection calculus – are pretty much the same whether you’re in Melbourne, Sydney, Perth, Adelaide or Auckland.

I would be more inclined to focus on the attractiveness of a city and measure how sought after it is (perhaps by looking at the difference between wages and housing costs). It’s instructive, I think, that few of the cities in the EIU’s top ten are the sorts of places young people around the world seem to aspire to live in. Let’s be realistic, Australian cities don’t have quite the drawing power of places like London, New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Paris.

The slightly different methodology used by the rival Mercer Quality of Living Survey ranks Sydney 10th and Melbourne 18th. This is a big drop in ranking for Melbourne compared to the EIU Survey, but again the difference in ranking is far larger than the difference in absolute scores, which is small. Read the rest of this entry »

Should Councils sell suburban parks to developers?

Posted: August 2, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: asset management, Brimbank City Council, Frederick Law Olmstead, Jan Gehl, Keilor Downs, open space, parks 13 CommentsThe Age reported on 28 July that Brimbank City Council is proposing to sell 14 parks in the municipality to developers. It followed up next day with an editorial, No walk in the park for Brimbank, lambasting the planned sale.

Selling parks?! I’d never heard of this proposal before, but I was aghast. I was amazed that any Council would sell off parkland, especially in the west, which we know from Melbourne 2030 is under-provided with regional parks relative to other parts of Melbourne. It didn’t surprise me to see that Brimbank is run by a Government-appointed administrator who presumably would be more inclined to put counting beans ahead of counting heads.

These must be significant parks, I figured, if The Age had written an editorial so quickly on the subject and published it alongside such weighty matters as its opinion on the carbon tax. I therefore read The Age’s editorial with great interest so I could see the issues laid out objectively and analysed dispassionately. I wanted to know which parks they were and what they’re like. I wanted to know what on earth Council could be thinking.

I have to say I was greatly disappointed. The editorial doesn’t make much effort to explain both sides of the story or lay out the ‘facts’. It notes Council says it will spend the proceeds to buy or improve more appropriate open spaces, yet it condemns Council’s position outright as selling “to developers in an apparent revenue raising exercise”. It’s made up largely of homilies like “public space belongs to the community”, “good quality public spaces are essential to build civic life and neighbourhood resilience”, “parks are part of the social glue of any suburb”, and so on.

The editorial even brings the spirit of Frederick Law Olmstead, the designer of Manhattan’s Central Park, to Keilor Downs. Olmstead, it argues, was “part of a movement in the 19th century that argued for parks and public recreation spaces as a means of overcoming isolation and suspicion”. Danish architect Jan Gehl’s claim that “as societies become more privatised with private homes, cars, computers and offices, the public component of our lives is disappearing” is also cited in support of the case.

This combination of blatant one-sidedness and over-reaching hyperbole put me on my guard. Of course it’s true parks are generally a good thing. And of course residents will generally be passionately opposed to losing something they’ve already got. But disposing of open space isn’t necessarily and automatically a bad thing – it depends on the circumstances. Read the rest of this entry »

Why are “Tribeca” and “Madison at Upper West Side” in Melbourne?

Posted: July 21, 2011 Filed under: Miscellaneous, Planning | Tags: BoCoCa, developer, Julie Szego, Madison at Upper West Side, neighbourhood, place name, real estate, Robin Boyd, Suliman Osman, Tribeca 13 Comments

The real Upper West Side, Manhattan - apparently you can now get all of this in Melbourne, Australia (much cheaper too!)

A few months ago, writer Julie Szego bemoaned the Americanisation of place names in Melbourne. She identified two examples – the “Madison at Upper West Side” development on the old Spencer St power station site and “Tribeca” on the former Victoria Brewery site in East Melbourne.

She invoked the spirit of Robin Boyd to explain just how easy it to sell the gloss and sparkle of New York to aspirational Melburnians:

Robin Boyd in The Australian Ugliness, the highly influential polemic about cultural cringe in the 1950s and early ’60s, observed that the most ”fearful” aspect of Australia’s low-rent mimicry of the American aesthetic ”is that beneath its stillness and vacuous lack of enterprise is a terrible smugness, an acceptance of the frankly second-hand and the second-class, a wallowing in the kennel of cultural underdog”

While Melbourne’s developers and apartment buyers pretend they’re living Sex in the City downunder, real New Yorkers are continuously inventing new, home-grown names to market projects. Here are six New York neighbourhoods you probably haven’t heard of:

SoLita: Downtown Manhattan, south of NoLita between Tribeca and Little Italy

FiDi: (Financial District, geddit?) Southern tip of Manhattan between the South Street Seaport and Battery Park City

BoCoCa: Brooklyn waterfront area comprising Boerum Hill, Cobble Hill, and Carroll Gardens, also known as Columbia Street Waterfront District

LIC: Southwestern waterfront tip of Queens, including Hunter’s Point (also known as Long Island City)

Two Bridges: Southeast of Chinatown beneath the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges

Southside: South part of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, near Williamsburg Bridge exit

Other examples – some of which resurrect old names or functions – include the Meatpacking District, Dumbo (Down Under Manhattan Bridge Overpass), East Williamsburg and Vinegar Hill. According to this writer, areas “like NoMad (north of Madison Square Park) and others like SoHa (south of Harlem) haven’t exactly caught on yet”. One commenter says that some, like Dumbo, were coined by the populace, not developers.

This has all gotten too much for certain New Yorkers. Suliman Osman reports that a Brooklyn (State) Assemblyman, annoyed that real estate agents are calling the area between Prospect Heights and Crown Heights “ProCro”, is calling for a Neighbourhood Integrity Act. One of his complaints is that rebranding lower income areas as hip could ultimately displace traditional residents. Read the rest of this entry »

Who lives in the city centre?

Posted: June 19, 2011 Filed under: Housing, Planning, Population | Tags: apartments, Core, demography, Inner city, Maryann Wullf, Michele Lobo, migration, Monash, overseas students 11 CommentsThere’s so much misinformation being put about lately regarding apartments and city centre living that I thought it would be timely to put some basic facts on the table. Fortuitously, I recently came across a paper by two academics from the School of Geography and Environmental Science at Monash University, Maryann Wullf and Michele Lobo, published in the journal Urban Policy and Research in 2009. It’s gated, but the tables I’ve assembled summarise most of the salient findings.

The authors examine the demographic profile of residents of Melbourne’s Core and Inner City in 2001 and 2006 and compare it against Melbourne as a whole i.e. the Melbourne Statistical Division (MSD). They characterise the Core as “new build” (60.6% of dwellings are apartments three storeys or higher) and the Inner City as “revitalised”.

The Core is defined as the CBD, Southbank, Docklands and the western portion of Port Phillip municipality i.e. Port Melbourne, South Melbourne and Middle Park. They define the Inner City as the rest of Port Phillip and Melbourne municipalities, plus Yarra and the Prahran part of Stonnington municipality. So what did they find? (but let me say from the outset that the implications and emphasis in what follows is my interpretation of the data, rather then necessarily theirs).

A key statistic is that the share of Melbourne’s total population who live in the Core is extremely small – just 1.7%. So however interesting the demography of the Core might be, it represents just a fraction of the bigger picture and accordingly we need to be very careful, I think, about assuming what goes on there reflects what the other 98.3% of Melburnians think, want or are doing. And the same goes for the Inner City, which has just 5.9% of the MSD population.

When the authors looked at the age profile of the Core they found it is astonishingly young. The proportion comprised of Young Singles and Young Childless Couples is an extraordinary 44.0%. The corresponding figure for Melbourne as a whole (i.e. the MSD) is 15.1%, or about a third the size. And just to emphasise the point of the previous para, note the Core has 26,486 persons in these two categories, whereas the MSD has 542,481.

Households in the Core also tend to be small with only 21.6% having children. In comparison, the MSD might as well be another country – the corresponding figure is 53.3%. Unfortunately the researchers don’t break down the large Young Singles group by household size, but given the predominance of apartments in the Core, it’s a fair bet they tend to live in one and two person households.

I expect it will surprise many to see that Mid-life Empty Nesters make up much the same proportion of the population in the Core (and Inner City) as they do in the MSD. They’re also a small group – they account for just 8.3% of the population of the Core and hence their impact on the demography of the city centre is really quite modest. Read the rest of this entry »

Were those the good old days?

Posted: June 14, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: 1954, Austerica, M I Logan, manufacturing, Planning for Melbourne's Future, Robin Boyd 6 Comments Here’s a fascinating look back to what planners (the MMBW) were thinking about Melbourne’s future nearly 60 years ago. In some ways not much has changed – like many contemporary planning proposals, this is propaganda but in those days they didn’t bother with thin disguise. I like the ending: “will it achieve your support?”.

Here’s a fascinating look back to what planners (the MMBW) were thinking about Melbourne’s future nearly 60 years ago. In some ways not much has changed – like many contemporary planning proposals, this is propaganda but in those days they didn’t bother with thin disguise. I like the ending: “will it achieve your support?”.

It seems that even as long ago as 1954, workers were spending two hours a day commuting and not only were roads congested but so were trams and trains!

The founders of the city could not visualise that one day workers who could walk to their jobs would spend more than one hour each day getting to and from their place of work, that trams would be unable to handle the peak hour crowds, that trains would become hopelessly inadequate for the handling of the enormous flow of commuters into and away from the city, and that with the coming of the motor car the original wide streets would become incapable of handling the ever increasing traffic flows”.

I’m surprised the introduction shows old buildings like Parliament House rather than new ones. After all, this was the new world of modernism and Robin Boyd’s famous attack on Austericanism – the “imitation of the froth on the top of the American soda-fountain drink” – was a mere three years away.

I’m also somewhat surprised that even as late as 1954 the CBD was seen as sucking the life out of inner city retail strips – presumably places like Smith Street – and the inner suburbs were in turn being invaded by industry:

As the city centre has grown in importance, many old shopping centres have declined and the living conditions in many of the surrounding suburbs have deteriorated. Industry had expanded into them and people have moved farther out to live. This has often resulted in an undesirable mixture of shops, houses and factories and the growth of slum conditions Read the rest of this entry »

– Where do university workers live?

Posted: March 30, 2011 Filed under: Education, justice, health, Planning | Tags: Census 2006, journey to work, La Trobe University, Melbourne University, Monash University, place of residence, staff, Sub region, workers 3 CommentsI’ve said before that there isn’t one ‘Melbourne’ – there are multiple ‘Melbournes’. The home range of Melburnians is pretty restricted – the great bulk of their travel is made within a region defined by their home municipality and contiguous municipalities. Many suburbanites rarely visit the city centre, much less the other side of town.

This pattern of sub-regionalisation is illustrated by Melbourne’s three major universities. I posted on March 16th about the mode shares of work trips to these universities. To summarise, at the time of the 2006 Census, 41% of Melbourne University staff drove to work while over 80% of staff at Monash and La Trobe Universities commuted by car.

The accompanying charts look at something else – where university workers lived in 2006. They show a number of interesting things.

The first chart indicates that staff of these three universities don’t tend to live west of the Maribyrnong. The west has 17% of Melbourne’s population but houses only 8% of Melbourne University’s staff. The ring road provides good accessibility from La Trobe to the west but even so, only 3% of the university’s staff live there.

Second, Monash and La Trobe serve distinct regional markets, in the north and south (of the Yarra) respectively. Melbourne University has a more metropolitan ambit but it still has a sub-regional focus – its staff strongly favour the inner city and the inner northern suburbs.

Third, university staff like to live close to their employer. This is particularly evident with La Trobe, where 56% of staff reside within the four municipalities closest to the university i.e. Darebin, Banyule, Nillumbik and Whittlesea (see second chart). Read the rest of this entry »

– Metro Strategy: (2) what are the challenges?

Posted: March 29, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: Matthew Guy, Melbourne 2030, Melbourne @ 5 Million, Metropolitan Strategy, Minister for Planning 8 CommentsYesterday I talked about what I thought the new Metropolitan Strategy for Melbourne should be. That was mostly ‘mothers milk’, so now I want to say something about the substance of the strategy – what it should do. I have (mostly) refrained from proposing specific policies or solutions, preferring instead to point out the key policy challenges or directions.

Among other things (this is not exhaustive) the new Metropolitan Strategy should:

Recognise that 90% of motorised travel in Melbourne is made by car and that there are myriad ways drivers and manufacturers are adapting to higher fuel prices. The great majority of travellers prefer to drive if they can despite the expense – they’re not going to give up driving for public transport unless they’re made to.

There are three key challenges in relation to cars. First, provide incentives to increase the speed of the transition to more fuel and emissions efficient vehicles. Second, make cars more civilised – make them slower and quieter and remove their priority over other carriageway users. Three, manage congestion so that gridlock is avoided and high value trips are given priority.

Recognise that public transport is only a substitute for cars in a limited number of situations. It has two key but growing roles. One is to transport large numbers of people to and from places with high trip densities, like the CBD, where the car is simply incapable of carrying so many people. The other is to provide mobility for those without access to a car.

The focus of public transport policy should be on these two roles. They mean a different approach to public transport from that implied by the popular idea that public transport must always be provided at a level which provides a “viable alternative” to car travel. Read the rest of this entry »

– Metro Strategy: (1) what should it be?

Posted: March 28, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: Matthew Guy, Melbourne 2030, Melbourne @ 5 Million, Metropolitan Strategy, Minister for Planning 4 CommentsThe Minister for Planning, Matthew Guy, has apparently told The Age that preparation of the Government’s promised metropolitan strategy has started and will be completed within two years.

I’ve previously pointed out some of the areas where I think Melbourne 2030 was found wanting, so I’ll offer some thoughts on what the new strategy should be and do, starting today with what it should be.

First, it should be a strategy for managing the growth of Melbourne. It can’t just be a land use plan, limited to the Planning Minister’s domain. It has to take a multi-portfolio view because planning is only one force shaping the way Melbourne will develop over the next 20, 30 or 40 years. In particular, it must recognise the intimate long-term, two-way relationship between land use and transport, both public and private.

Second, it should positively embrace so-called ‘soft’ policies like regulation, taxation and marketing. It must not limit its perspective solely to ‘hard’ initiatives like capital works and zoning regimes. These are important because they’re long term decisions, but how Melbourne develops in the future will be shaped as much by how behaviour is managed as by what projects are constructed. There are, for example, a host of regulatory and taxation policies – e.g. road pricing – that can potentially have a profound impact on shaping the way the city develops (and not all of them are as politically fraught as road pricing). Some can obviate the need for capital works.

Third, it should focus single-mindedly on what can be done most efficiently and effectively through a growth management strategy. It should resist the temptation to ‘solve’ every economic, social and environmental issue confronting Melbourne. Sometimes what are seen as urban issues are more the symptom of other processes rather than the underlying cause – I’ve previously suggested that diversity is one such issue. It’s important that the strategy understands how it impacts on, or even exacerbates, variables like diversity, but close attention should be given to whether or not it is the appropriate vehicle to achieve change. Read the rest of this entry »

Will E-Gate curb suburban sprawl?

Posted: March 10, 2011 Filed under: Housing, Planning | Tags: brownfield, Denis Napthine, Docklands, e-Gate, Fishermans Bend, Major Projects, redevelopment, Richmond station, The Age, urban renewal 4 CommentsI like the (very) notional plans for redevelopment of the old E-Gate site in west Melbourne to accommodate up to 12,000 residents published in The Age (Thursday, 10 March, 2011).

Putting what might be 6,000–9,000 dwellings on 20 highly accessible hectares on the edge of the CBD makes a lot more sense than the mere 10,000–15,000 mooted for 200 hectares at Fishermans Bend.

But I do take issue with the claim by the Minister for Major Projects, Denis Napthine, that it’s a very significant development for Melbourne “because we want to grow the population without massively contributing to urban sprawl”.

The Age reinforces this take by titling its report “New city-edge suburb part of plan to curb urban sprawl” and goes on to say that it’s the first big part of the Government’s “plan to shift urban growth from Melbourne’s fringes to its heart”.

I’ve always liked the idea of E-Gate being redeveloped but, as I said on February 19 in relation to a similar report on proposals for Fishermans Bend, the significance or otherwise of the project for fringe growth has to be assessed in the context of the total housing task for Melbourne.

In the twelve months ending 30 September 2010, 42,509 dwellings were approved in the metropolitan area, of which around 17,000 were approved in the outer suburban Growth Area municipalities. That’s just for one year. E-Gate’s 6,000 – 9,000 dwellings would be released over a long time frame, probably at least ten years and quite possibly longer (the Government says Fishermans Bend will be developed over 20-30 years). Existing leases on the site run till 2014 so it’s likely the first residents won’t be moving in for a long time yet.

Of course it all helps but the contribution of the three redevelopment sites identified by the Government – E-Gate, Fishermans Bend and Richmond station – to diminishing pressure on the fringe will be modest. They don’t collectively constitute a sprawl-ameliorating strategy. Melbourne still needs a sensible approach to increasing multi-unit housing supply across the rest of the metropolitan area. The “brownfield strategy” is in danger of becoming “cargo cult urbanism”.