Are we squandering infill housing opportunities?

Posted: December 5, 2011 Filed under: Housing, Planning | Tags: Alphington, councils, density, dual occupancy, infill, medium density housing, third party appeals 29 CommentsI’ve argued before (here, here and here) that new housing supply within Melbourne’s established suburbs is excessively dependent on small-scale infill housing projects. In the expansive middle ring suburbs, around half of all housing projects provide only one or two additional dwellings, with the great majority providing only one.

It’s therefore important to look at other options, but given it’s carrying most of the burden, it’s also worth asking if infill is being managed as efficiently as it could be.

The exhibit above shows a newly completed infill development at 2-4 Old Heidelberg Rd in suburban Alphington (here are some interior pictures). It provides eight dwellings on an 825 sq m site that originally would’ve been intended to accommodate a single detached house like its neighbour.

That’s a big up-lift in density – if most infill projects yielded this many new dwellings we wouldn’t have a supply problem. But the great bulk are simple dual occupancy developments. This raises the important issue of whether we’re maximising the value we’re getting from the limited supply of precious infill sites.

If projects that could yield four, six or eight new units are only providing one, then that could represent a very high opportunity cost. Given that activity centres in the middle ring suburbs are mostly failing to deliver much new housing, what we ideally want to see is each lot delivering to its full potential – yielding the maximum number of new dwellings that, having regard to its particular circumstances, it reasonably could.

There are of course many “objective” reasons why not all projects can yield as many dwellings as 2-4 Old Heidelberg Rd. Some redevelopment sites are small or inconveniently shaped. Some may have infrastructure inadequacies or access might be hard.

There are also a range of legitimate planning constraints like heritage, over-looking and solar access that might limit the number of units that can be built on a given lot. And the nature of the market in a particular area could mean the highest return comes from building fewer dwellings rather than maximising the total number.

But there are reasons to suspect that “objective” factors do not always, or even usually, explain why a lot isn’t developed to its potential. Consider these two contiguous lots in Elphin St Ivanhoe – although they’re the same size and have a common context, one has six dwellings and the other has two.

The most commonly cited explanation for these sorts of anomalies is the “dead hand” of the planning system. Additional cost and risk is imposed on projects by self-interested opposition from existing residents. Councils often lack the resources and skills to deal with the complexity of sophisticated opposition and, not surprisingly, often take a position more sympathetic to their constituents than to the developer.

There’s a range of measures that have been suggested to tilt the balance more toward redevelopment. These include abolition of third party appeals (the issue got a run in The Age recently), code-based approval systems, more resources for councils, better forward planning, and so on. I endorse this position but there’s no doubt it’s very hard politically, both for councils and the state government.

I think there’s another approach that’s worth thinking about, particularly for the middle ring suburbs. We know infill developers tend to be small and it could be that many simply lack the knowledge, skills, access to finance and appetite for risk to enable them to undertake larger projects. They might not have the wherewithal to push for larger projects in the face of vigorous opposition from neighbours and limited support from timid councils.

Perhaps the project class with the greatest potential for “under-utilisation” is dual occupancy. Landowners carve off a bit of land and sell it, usually for the construction of one additional dwelling. That way they get to stay in their old house and transform some excess land into cash without taking much risk.

That’s a net addition to supply so it’s positive. While in many cases the value of the existing dwelling will preclude more intense development, dual occupancy is a lost opportunity if the entire site could’ve been successfully redeveloped for four, six or eight dwellings. Read the rest of this entry »

Can Melbourne depend on infill housing?

Posted: November 22, 2011 Filed under: Housing, Planning | Tags: activity centre, City of Monash, Housing, infill, Jim Petersen, medium density, Monash University, Rail station, Shobit Chandra, Thu Phan 13 Comments

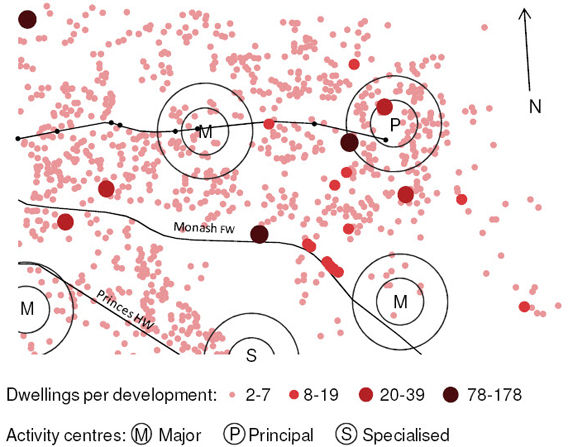

Geography of infill developments in City of Monash, 2000-2006 (source: Phan et al, 2008 - graphic via Grattan Institute)

We know that the inability to increase significantly the supply of dwellings within established suburbs is a key failing of strategic planning in Melbourne. Simply put, there’s not enough housing to make established suburbs affordable for all the people who would like to live in a relatively accessible location.

We also know that activity centres aren’t pulling their weight in the task of increasing supply (see here and here) and that the burden of supply is instead falling on small-scale infill development, much of it dual occupancy projects. So it’s worth looking further at the nature of infill housing.

A study by Monash University’s Thu Phan, Jim Peterson and Shobhit Chandra , Urban infill: the extent and implications in the City of Monash, examined new developments in the municipality over the period 2000-06. They defined infill primarily as projects where two or more new dwellings were constructed on sites formerly occupied by detached houses. A total of 1,483 projects were identified, ranging in size from two dwellings to 178.

The study revealed a number of interesting aspects about this middle suburban municipality.

First, it found new dwelling supply is dominated by small projects. One project built more than 178 dwellings and three built between 40-77 dwellings, however 98% of projects involve just 2-7 seven dwellings (and we can be pretty confident they’re heavily weighted toward the smaller end).

Second, projects are dispersed, not concentrated. As shown in the exhibit, proximity to major trip generators is uncorrelated with location of projects. Just 5% are within 400 metres of a Principal, Major or Specialised activity centre, and only 10% are within 400 metres of a rail station. Moreover, the authors found projects located within 400 metres of an activity centre are smaller on average than those in more distant locations.

Third, developers tend to be opportunistic rather than strategic – they wait for properties to be offered for sale and assess each one on its potential for redevelopment. Thus the geography of infill development is shaped largely by what comes on the market rather than by any sort of deterministic planning policy.

Fourth, the size of lots and the age of the existing house is a more important influence on the location of infill development than proximity to an activity centre or rail station. The average infill site is relatively large (700 to 900 sq m) and the majority of existing dwellings are relatively old i.e. built between 1945 and 1965. Lot sizes close to rail stations are smaller – and hence less amenable to redevelopment – than those further away, probably reflecting the different periods of development.

Thus not only are activity centres failing to expand housing supply in accordance with the precepts of Melbourne 2030, but the great bulk of new housing being built in Monash isn’t located close to activity centres but rather is dispersed (relatively uniformly too judging by the exhibit i.e. non-randomly).The dispersed pattern will worry some, but I don’t see it as a big issue. Read the rest of this entry »

Are real estate agent fees limiting residential mobility?

Posted: November 17, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: ABS, commission, Consumer Affairs Victoria, Grattan Institute, household size, real estate agents 10 CommentsDespite an enormous increase in house prices over the last ten years, real estate commissions stayed relatively constant as a percentage of selling price. Agents consequently enjoyed a spectacular increase in the dollars earned on each sale even as the volume of sales was expanding.

In its new report, Getting the housing we want, the Grattan Institute notes real estate commissions are so big they’re a significant barrier to residential mobility in most States. This is an important public policy issue – the ABS reports that even though average household size is falling, the average number of bedrooms per household is increasing (see exhibit). Any barriers that constrain households from voluntarily moving to dwellings that better match their size should to be addressed. And the same goes for barriers that limit their ability to reduce travelling costs by moving to a new residential location.

In most industries, when firms start earning super-profits we would expect prices to be moderated by an increase in competition. However as the Institute observes, this hasn’t happened with real estate agents – competition is weak:

This is consistent with the industry elsewhere, too – the UK Office of Fair Trading recently conducted a review of UK real estate buying and selling. It found that while 32% of those who had used a traditional real estate agent believed that the fees represented either slightly or very poor value for money, 64% said that they did not negotiate a lower fee.

In Victoria, as in most States, there is no set commission, giving the impression of a lightly regulated industry. Vendors and agents are free to work out whatever arrangement they wish, whether it be a fixed sum, a sliding scale, or something else. However according to this real estate consulting group, the customary fee paid by vendors in Melbourne ranges from 1.6% to 2.5% of the selling price. This doesn’t include advertising or even a property sign – marketing is an extra cost borne by the vendor.

This introductory “how to” guide on buying and selling issued by Consumer Affairs Victoria implies an even higher commission. It illustrates a lesson on negotiation between a vendor and agent with an assumed commission of 3.3% up to $500,000 and 3.85% thereafter (p 22). That’s a $16,500 commission on a $500,000 property. I think there’s a fair chance the target market for the guide will interpret this illustration as somewhere around the “going rate”.

There’s hopefully an extensive literature that looks at why the cost to vendors has risen so much and why competition is so weak. If there is I’m not familiar with it and I don’t have time to read it anyway. It seems to me, though, that the internet should’ve reduced considerably the cost to agents of finding prospective buyers and that a good part of those savings should’ve been passed on to vendors. It also should’ve made it easier for innovators to enter the industry and set up new lower-cost business models. Read the rest of this entry »

Has the Grattan Institute got the answer to our housing woes?

Posted: November 15, 2011 Filed under: Activity centres, Housing | Tags: e-Gate, Getting the housing we need, Grattan Institute, Places Victoria, The Housing We'd Choose, VicUrban 8 Comments

Housing preferences compared with existing stock and the composition of current housing supply (by Grattan Institute)

I have to say right up-front that I’m disappointed by The Grattan Institute’s new report, Getting the housing we want. It nominally proposes ways of increasing housing supply in established suburbs, but it really just puts up the politician’s standard solution – more bureaucracy, more money, and little explanation (press report here).

In the Institute’s defence, I must acknowledge that it’s taken on a difficult task. It’s much harder to propose practical solutions than it is to analyse problems, identify key issues and propose general directions for action. And the Institute has hitherto done a good job on the latter three tasks with a series of reports under its Cities Program.

The new book by Harvard economist Edward Glaeser, Triumph of the City, illustrates the way solutions attract criticism. The book was lauded for its sophisticated analysis of the benefits of density and the need to remove the many obstacles to redevelopment. But his big idea for an historic buildings preservation quota – meaning that cities could only protect a set number of buildings each year and so would be forced to prioritise – was lambasted by all and sundry as impractical and, worse, naïve.

A lot of critics had a similar reaction to Ryan Avent’s The Gated City. Great analysis of the need to promote density, they said, but potential solutions to NIMBYism like developers compensating neighbours for the negative effects of development were criticised as unworkable and unrealistic. As soon as detailed, practical solutions are suggested, the knives come out!

So the Grattan Institute is putting its corporate head on the line with the solutions-oriented Getting the housing we want. It’s a follow-up to the Institute’s earlier report, the impressive The Housing we’d choose. The earlier report established that there’s a significant mismatch in Melbourne and Sydney between where many people actually live and where they’d like to live (see my earlier discussion of this report).

Opposition from existing residents to redevelopment proposals is a key reason for this misalignment – they don’t see the broader good and they don’t see how redevelopment benefits them. Councils tend to fall in behind residents who’re committed in their opposition to redevelopment.

The new report is on safe and familiar ground when it advocates standard stuff like code-based approval processes for small-scale development. However its headline proposal is more problematic – the Institute proposes the establishment of Neighbourhood Development Corporations (NDCs), with initial financing coming from a proposed new Commonwealth-State Liveability Fund.

The idea is NDCs would undertake large scale redevelopment projects aimed at increasing housing supply. NDCs would be “independent”, not-for-profit organisations that work in “partnership” with all tiers of government, the private sector and residents. The Institute stresses the importance of in-depth consultation and says NDCs could only “go ahead with the support of local residents”. NDCs would have to provide a diversity of housing “in terms of both type and price” and would have “temporary planning powers”.

Disappointingly, there’s not a lot of concrete information in the report on the mechanics of the proposed NDCs and Liveability Fund. And there’s little specific analysis and justification provided in support of these ideas. However the report profiles three examples of existing organisational structures similar to what’s envisaged with NDCs. These are London Docklands Development Corporation; HafenCity Hamburg, and Bonnyrigg social housing estate.

These throw more light on what the Institute envisages. They make it clear NDCs are conceived primarily as mechanisms for managing large sites like E-Gate which are invariably disused, underutilised or owned largely by government. The familiar redevelopment challenges of land assembly, existing uses and resident opposition are usually much more tractable with these sorts of sites than they are with activity centres (e.g. see discussion of proposals for Ivanhoe).

I have trouble enough with the idea that changing management structures is the broom that will sweep away all the gunk that’s holding up supply. But the trouble with having such a narrow ambit is that the potential contribution NDCs can make to increasing housing supply is necessarily more limited. Moreover, it begs the question of whether NDCs are even necessary. Read the rest of this entry »

Would Seaside work in outer suburban Melbourne?

Posted: September 26, 2011 Filed under: Housing, Planning | Tags: Florida, new urbanism, Seaside, The Truman Show 13 CommentsWhen I first saw pictures of Seaside many years ago, I imagined that’s what the outer suburbs of Melbourne could look like one day. Click on the picture and go for a “walk” around the Florida village that had a key role in inspiring the New Urbanism movement. Seaside is famous – you might know it from its role in The Truman Show or from its distinctive array of “story book” houses.

Although the houses are detached, you’ll see many of the key ideas of New Urbanism in Seaside, including houses that open up to neighbourly streets and paths, have no garages and are within an easy walk of the town centre. Keep an eye out for walking paths. Given the kind of detached housing that’s being built today in Australian cities, I find it extraordinary that the first stage of Seaside was started 30 years ago!

It doesn’t push all the New Urbanism buttons. For example, the range of dwelling types is pretty limited and there’s not much evidence of transit orientation (it’s not a commuter village). Nevertheless, average density approaches the aspirational 25 dwellings per hectare, well in excess of the 15 dwellings per hectare promoted in Melbourne 2030 and in new fringe structure plans like the one for Toolern, near Melton.

For my money, the key reason Seaside has such broad popular appeal is the two and three storey detached “Hansel and Gretel” houses, with their faux widow’s walks and sometimes extravagant follies. Some architects however find it twee – they wince at the sentimentality and overwrought quaintness of the place.

I think it also appeals because of the determination of the architects to eliminate garages. This enables living areas to be placed at the front within a conversation’s distance of the sidewalk. It captures a half-forgotten notion of neighbourliness and conjures romantic images like promenading.

This contrasts with the practice in Melbourne where both new suburban houses and traditional inner city terraces tend to put bedrooms at the front and the main living areas at the rear (only apartments and older suburban houses seem to have living areas facing the street, although they’re usually set way back from the front boundary).

A parallel with Melbourne though is the limited area of private open space. I hear frequent condemnation of big houses with small yards in Melbourne’s outer suburbs (as if buyers can’t make their own decisions about what size yard they want!) but the area of private open space in Seaside looks positively miniscule. As with apartment dwellers, I’d expect the quality of the public realm is an important offset.

As a possible model for Australian suburbia, it’s important to get Seaside in context. It’s not a big place – it only covers about 50 32 hectares (the part of Fishermans Bend mooted for redevelopment is 200 Ha) and has around 500 houses. (Update: the whole area though, including very similar contiguous developments, is about 100 Ha with 1,000 or more houses – see Comments). Also, it’s essentially a beachside resort for people who are well-off. Many of the houses are rented to holiday makers and in that sense it functions more like the swank residential areas close to Hastings Street in Noosa than the suburbs of Melbourne or Sydney.

Like Noosa, it’s a long way from the nearest major urban centre. Dwellings are architect-designed and costly to build – properties at Seaside have sold for as much as $5 million (presumably ones on the beachfront). Further, I suspect a major reason there are so few cars in the streets is that holiday makers fly in and have no need to drive in what is essentially a self-contained resort. The town centre seems improbably built-up for 500 dwellings and that could be because this is a tourist town, drawing visitors from well beyond Seaside’s border.

I can imagine something like Seaside working on old brownfield sites in Melbourne like Fishermans Bend and E-Gate, but what would happen if it were transplanted to the suburban fringe? Read the rest of this entry »

Have buyers abandoned McMansions (forever)?

Posted: August 17, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: CEDA, house size, Housing, Mark Hunter, Mark Quinn, McMansions, Stockland, UDIA 4 Comments It only seems like yesterday we were told Australia had the largest new houses in the world (e.g. see here and here). Now it seems we’ve seen the error of our ways. According to this press report, the head of residential communities at property developer Stockland, Mark Hunter, has no doubt the era of ever-growing McMansions is over – he expects home sizes to shrink as fast as they grew in the first decade of this century. Mr Hunter is reported as saying three-bedroom, two bathroom houses are the new sweet spot in the market:

It only seems like yesterday we were told Australia had the largest new houses in the world (e.g. see here and here). Now it seems we’ve seen the error of our ways. According to this press report, the head of residential communities at property developer Stockland, Mark Hunter, has no doubt the era of ever-growing McMansions is over – he expects home sizes to shrink as fast as they grew in the first decade of this century. Mr Hunter is reported as saying three-bedroom, two bathroom houses are the new sweet spot in the market:

With power prices increasing, people want more efficient homes and are happy to sacrifice extra bedrooms, rumpus and media rooms and make do with a single open-plan living and dining area opening onto an outdoor area.

Stephen Albin, the chief executive of the Urban Development Institute of Australia, says the trend to shrinking new home sizes is only just beginning:

I think there’s a massive shift going on and we are at the front end of it. People are starting to realise a five-bedroom house has other costs, from the amount of leisure time you lose maintaining it, to heating and cooling, and you are going to start to find we are at the front end of that shift

He sees a permanent change in Australians’ preferences. “The McMansion’s days are numbered”, he asserts, “just look overseas and see what’s happening”.

In a recent address to CEDA, the CEO of Stockland, Mark Quinn, argued that people are choosing less debt over having five bedrooms and a separate dining room they use once a year at Christmas. People are more patient now, he said, and rather than seek instant gratification they “prefer to wait and have less debt”.

Have Australian fringe buyers really lost their taste for big houses virtually overnight? And is this really a permanent change – is it a “paradigm shift”? Only a few months ago we were debating in these pages home buyers’ preference for seemingly ever-larger dwellings!

I’m hard pressed to see it. Sure, electricity prices – which really could drive a permanent shift toward downsizing – look like they’ll keep rising, but as I’ve pointed out before, there have been massive improvements in the operational energy efficiency of new detached houses over the last ten years. The per capita operating energy required by the average new greenfield dwelling in 2008 was about a third lower than it was in 2000. In fact it was lower than it was in 1960, nearly 50 years earlier, notwithstanding the size of the average new greenfield dwelling more than doubled over this period.

The latest edition of Property consultant Oliver Hume’s Survey of purchaser sentiment in Melbourne’s Growth Areas doesn’t suggest buyers tastes have changed. When the company asked land buyers what size house they intended to build, the proportion who said greater than 279 sq m was the same in June 2011 (30%) as it was in December 2010 (Oliver Hume say the actual size buyers end up building is about 50 sq m smaller). Read the rest of this entry »

Are too many houses empty?

Posted: July 26, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: dwellings, Earthsharing Australia, REIV, unoccupied properties, vacancy rate 4 Comments

Earthsharing Australia - Suburbs with highest proportion of properties withheld from rental market (last col)

Earthsharing Australia highlighted this week what could be a major housing supply issue in Australia’s major cities: the number of houses sitting vacant at any one time. Properties will inevitably be vacant from time to time – that’s necessary for an efficient market – but the issue is whether there are structural factors that mean too many are unoccupied for too long.

Earthsharing has attempted to quantify the number of unoccupied dwellings in Melbourne. It claims speculators are the reason why five per cent of the city’s housing stock – or 46,220 dwellings – sit empty and unrented at any time. It says the REIV’s Rental Vacancy rate is commonly referred to in media coverage as the ‘housing vacancy’ rate, but Earthsharing’s own:

Estimated Speculative Vacancy Rate (of 4.9%) is more than twice the REIV’s Rental Vacancy rate for the same period of 1.7%…….Recent increases in house prices have been driven by speculation, not a housing shortage. Property buyers are restricting the supply of housing by holding their properties off the rental market.

The Estimated Vacancy Rate for some suburbs was much higher – in Docklands it was 23% and in East Melbourne, 19% (referred to in the exhibit above as Estimated Genuine Vacancy rate).

Earthsharing’s findings are contained in a report released on the weekend, Speculative Vacancies in Melbourne 2010, which measured the number of houses (excluding the area covered by South East Water) that consumed less than 50 litres of water per day, on average, over a period of six months in 2010. The presumption is dwellings using less than this amount must be unoccupied, given that average daily consumption during the period of the study was 140-160 litres per day. The further assumption is these dwellings have been withheld from the rental market for speculative reasons.

Earthsharing’s Speculative Vacancy rate could be conservative. Unoccupied dwellings with an automatic sprinkler system or a serious leak might consume more than 50 litres per day and hence be under-counted. On the other hand, its methodology could over-count the number of unoccupied dwellings. There’s some evidence consistent with the latter view – of the 46,200 properties identified by Earthsharing as “withheld from the market”, only 15,237 consumed zero litres of water over the six month period, and hence could be regarded as unambiguously vacant.

In fact there are many reasons why a property might be occupied but nevertheless average less than 50 litres per day over six months. Apart from rental dwellings between leases, some properties are unoccupied because they’re being sold by one owner-occupier to another. There are city properties owned by country people who use them regularly but relatively briefly e.g. a weekend every fortnight. Then there are single person households who travel frequently or for extended periods, as well as “couples” where each party has their own home but they favour one.

It might be possible to refer to these sorts of properties as “under-occupied” in the same sense that empty nesters rattling around in four bedroom houses is “inefficient”, but it would be a big stretch to label them with a pejorative like speculative. These aren’t properties that are being withheld from the rental market. In short, Earthsharing’s methodology doesn’t seem very robust.

But having said that, I suspect there are far too many non-rental properties that sit unoccupied for unnecessarily long periods. Let me emphasise that I don’t have any objective data to support this contention, but if it’s right, it would add to pressure in the rental market. Consider that within 500 metres of my place (I live 8 km from the CBD) there are four properties I’m aware of that have sat vacant in recent years for twelve months or more. Read the rest of this entry »

Why is housing in European rural villages so dense?

Posted: July 25, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: Alexis DeTocqville, Cadel Evans, Castelnuovo di Garfagnana, density, Parrot and Olivier in America, Peter Carey, rural village, Tour de France 11 CommentsI can’t let the Tour de France go by without finding some way to reference this great spectacle and Cadel Evan’s singular achievement.

Something I noticed watching the Tour is how traditional French country villages have relatively high density housing compared to Australian country towns. I’ve seen the same pattern in the Italian countryside – villages of three storey (or more) apartments set within productive agricultural land.

Yet in contrast, Australian country towns are predominantly detached houses on large lots. Only the odd commercial building – like pubs – is two storeys. Why didn’t town dwellers in Australia choose to live in multi-storey buildings like Europeans?

I don’t know the answer but it’s worth thinking about and so I’m hoping someone does. There’s a host of potential explanations. It might be the car, yet parts of Australian country towns that pre-date motorisation are lower density than their European equivalents. It might have something to do with differences in the value of agriculture, yet there are some Australian towns where agriculture must’ve been of comparable or higher value than many areas of Europe e.g. wine growing regions.

Perhaps building materials were generally harder to get than in Australia – i.e. more expensive –and this encouraged smaller dwellings. Maybe the more extreme climate had an influence too, giving residents an incentive to cluster buildings for better insulation. I also wonder if there was a different tradition of village housing in England compared to the rest of Europe that was followed by early settlers in Australia.

Perhaps it was driven as much by politics as by anything else. I recently read Peter Carey’s Parrot and Olivier in America, which is loosely based on the book, Democracy in America, which French aristocrat Alexis DeTocqville wrote after touring the young democracy in the early 1830s. I was struck by the enormous gulf in the world views of the aristocracy and the common people in France at this time. So perhaps it was in the interest of the local aristocrat in country areas to maximise the amount of land in agricultural use and minimise the quantity of land and resources devoted to housing the peasants. However once the “common man” settled in the New World he could make his own choice about how much space to devote to housing and how much to agriculture.

As I say, I don’t know but I’d be interested to hear other’s views.

Are McMansions about class warfare?

Posted: July 18, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: Beached House, Blogger on the cast iron balcony, Club Troppo, Don Arthur, McMansions, sustainability, urban fringe 13 Comments

It's big, but who would dream of calling it a McMansion? It's Beached House, a winner in this year's Victorian architecture awards

There was a very interesting trans-blog discussion over the weekend about one of my favourites topics – McMansions. It started earlier in the month when Helen at Blogger on the Cast Iron Balcony decided to “call bullshit on the popular story that criticising McMansions is equivalent to sneering at the working class, and denying them the good things in life”. She goes on:

In this narrative, the people championing the McMansion are the true socialists and stand with the working man and woman in their quest for a truly equal society.

She reckons it’s nothing to do with class. Her alternative interpretation is that McMansions are objectively just plain bad. That’s partly, she says, because they’re shoddily built, partly because they’re environmentally greedy, and partly because buyers are unwittingly duped by advertisers and marketers into wanting these big status machines.

Don Arthur at Club Troppo picked up on Helen’s post in passing on Friday in his regular Friday Missing Links. He must’ve been intrigued by the debate because he returned on Sunday with a nice, measured commentary on the topic, Together alone, why McMansions appeal.

I’m not going to get into the detail of this debate because I’ve looked at it before (e.g. see here, here, here and here, or go to Housing in the Categories list in the sidepane for a larger selection). However I do want to summarise in twelve simple points what I think are the salient matters in this ongoing debate.

One, what we call a McMansion in Australia is modest compared to the way the term is used in the US where it originated. In the latter McMansions are palaces, but here in Australia, any outer suburban two story home and garage produced by a developer, whatever its size, seems to attract the pejorative, McMansion.

Two, only cookie cutter houses constructed by developers are McMansions. Large architect-designed bespoke detached houses like these aren’t described in such sneering, deprecating terms.

Three, the great majority of fringe dwellings don’t fit the popular definition of a McMansion. For example, in Melbourne, more than two thirds of all houses built in the Growth Areas are single story (however for some critics that means little – they implicitly regard all detached fringe houses as McMansions).

Four, buyers of McMansions aren’t from struggle town – they’re overwhelmingly 2nd and 3rd home buyers.

Five, fringe area McMansions aren’t appreciably bigger, if at all, than all those renovated detached homes within established suburbs. The latter have the advantage of larger sites, so there’s scope to extend further. When account is taken of relative household size, the difference in per capita space between McMansions and established homes – such as those occupied by empty nesters – is likely to be even smaller.

Six, there’s no evidence McMansions are more shoddily built than smaller fringe dwellings, or apartments for that matter. That’s just out and out prejudice. Read the rest of this entry »

Where are architects going with housing?

Posted: June 30, 2011 Filed under: Architecture & buildings, Housing | Tags: A'Beckett Tower, AIA, Architects Institute Australia, architecture, awards 2011, BKK Architects, Elenberg Fraser, Hayball, Muir and Mendes, NMBW Architecture Studio, Sally Draper Architects 9 Comments

A'Beckett Tower - Winner 2011 Victorian Architect's Institute Award for multiple residential (two bed unit)

Victoria’s architects had their annual awards ceremony last Friday, handing out gongs in a range of categories. Curiously, the official AIA site shows the happy faces of the winning architects, but no pictures of the winning buildings. It should have both! Nevertheless, I finally succeeded in locating a file showing pictures of all the winning buildings in all categories – see Award Winners 2011.

Given the pressing housing issues facing our cities – like declining affordability and the need for higher densities in established suburbs – I was curious to see what the best architects in the State were doing in housing design, so I took a look at the winners in the New Residential Architecture category.

The premier honour for residential architecture in Victoria – The Harold Desbrowe-Annear Award – was won by NMBW Architecture Studio for a house in Sorrento. This is a detached house on a relatively large lot. In fact it could be is an up-market beach house.

There were three other winners in the New Residential category. Two of them – Beached House, by BKK Architects, and Westernport House, by Sally Draper Architects – are also detached houses in relatively remote (from Melbourne) locations, seemingly on even larger lots.

The only winner located in a metropolitan setting is the Law Street house, built for their own use by husband and wife architects, Amy Muir and Bruno Mendes. I like it, but architect’s own houses don’t generally provide a template for addressing the wider task of housing the population at large.

In contrast, there were only two awards for higher density housing. The premier Best Overend Award for Multiple Residential went to architects Elenberg Fraser for the A’Beckett Tower (see exhibits) and the other to Hayball architects for a three storey development in John Street, Doncaster. Read the rest of this entry »

What type of housing do we prefer?

Posted: June 25, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: apartment, detached house, Grattan Institute, Housing, preferences, stock, The cities we need, The Housing We'd Choose, town house 6 CommentsThe Herald-Sun reported last week that “the great Australian dream of owning a home on a quarter-acre block might no longer exist. Instead, Australians want more town houses and apartments in the more desirable areas”.

The important words are the last five – “in the more desirable areas”. Australians still love their big, detached houses but they also value location. The baby boomers could have a detached house on the suburban fringe and still have reasonable access to the rest of the city, but those days are vanishing. Now, people who want to live in an accessible location increasingly have to forgo space and accept a smaller dwelling, often a town house or apartment. As illustrated here, those leading this trend are young, small households without dependents – they’re less sensitive to space than families and place a higher value on density.

The Herald-Sun’s interest in this issue was sparked by a new study by the Grattan Institute, The Housing We’d Choose, on the housing preferences of residents of Sydney and Melbourne. It shows that more than half of households in these cities would rather live in a multi-unit dwelling in the right location than in a detached house in the wrong location.

This presents a serious problem for policy – the existing stock of housing no longer matches up with resident’s changing preferences. The Institute finds that a whopping 59% of Sydneysiders and 52% of Melburnians would prefer some form of multi-unit living. Yet this type of dwelling makes up only 48% and 28% respectively of the existing housing stock in the two cities (see first exhibit). Moreover, in Melbourne, developers are continuing to under-provide medium and higher density housing, leaving households with little choice other than to live in sub-optimal locations, albeit in a detached house.

I must admit I was disappointed with the Grattan Institute’s first report in its Cities series, The Cities We Need, so I wasn’t expecting a lot from The Housing We’d Choose. It’s not that there was anything technically wrong with the first report, it’s just that it seemed a curiously pointless exercise – as I noted here, it’s so high-level it didn’t take the debate on urban issues anywhere or advance the cause of better policy.

This time however the Institute has applied all those brains and resources to a meaty and relevant issue and, moreover, gone about it in a logical and determined way. While The Housing We’d Choose has some flaws, it shows up the limitations of the research being churned out by some of our local universities and lobby groups. This is the kind of study they should be examining closely.

The headline finding – that people are prepared to trade off dwelling size and type for greater accessibility – may seem self-evident, but the Institute has attempted the important task of measuring this preference. The researchers sought to simulate real life. They gave a sample of households in the two cities a range of real location, housing type and dwelling size options and asked them to make trade-offs in order to arrive at their preferred combination. The smart thing is the trade-off was constrained by real-life prices and the real incomes of respondents. Read the rest of this entry »

Who lives in the city centre?

Posted: June 19, 2011 Filed under: Housing, Planning, Population | Tags: apartments, Core, demography, Inner city, Maryann Wullf, Michele Lobo, migration, Monash, overseas students 11 CommentsThere’s so much misinformation being put about lately regarding apartments and city centre living that I thought it would be timely to put some basic facts on the table. Fortuitously, I recently came across a paper by two academics from the School of Geography and Environmental Science at Monash University, Maryann Wullf and Michele Lobo, published in the journal Urban Policy and Research in 2009. It’s gated, but the tables I’ve assembled summarise most of the salient findings.

The authors examine the demographic profile of residents of Melbourne’s Core and Inner City in 2001 and 2006 and compare it against Melbourne as a whole i.e. the Melbourne Statistical Division (MSD). They characterise the Core as “new build” (60.6% of dwellings are apartments three storeys or higher) and the Inner City as “revitalised”.

The Core is defined as the CBD, Southbank, Docklands and the western portion of Port Phillip municipality i.e. Port Melbourne, South Melbourne and Middle Park. They define the Inner City as the rest of Port Phillip and Melbourne municipalities, plus Yarra and the Prahran part of Stonnington municipality. So what did they find? (but let me say from the outset that the implications and emphasis in what follows is my interpretation of the data, rather then necessarily theirs).

A key statistic is that the share of Melbourne’s total population who live in the Core is extremely small – just 1.7%. So however interesting the demography of the Core might be, it represents just a fraction of the bigger picture and accordingly we need to be very careful, I think, about assuming what goes on there reflects what the other 98.3% of Melburnians think, want or are doing. And the same goes for the Inner City, which has just 5.9% of the MSD population.

When the authors looked at the age profile of the Core they found it is astonishingly young. The proportion comprised of Young Singles and Young Childless Couples is an extraordinary 44.0%. The corresponding figure for Melbourne as a whole (i.e. the MSD) is 15.1%, or about a third the size. And just to emphasise the point of the previous para, note the Core has 26,486 persons in these two categories, whereas the MSD has 542,481.

Households in the Core also tend to be small with only 21.6% having children. In comparison, the MSD might as well be another country – the corresponding figure is 53.3%. Unfortunately the researchers don’t break down the large Young Singles group by household size, but given the predominance of apartments in the Core, it’s a fair bet they tend to live in one and two person households.

I expect it will surprise many to see that Mid-life Empty Nesters make up much the same proportion of the population in the Core (and Inner City) as they do in the MSD. They’re also a small group – they account for just 8.3% of the population of the Core and hence their impact on the demography of the city centre is really quite modest. Read the rest of this entry »

Are huge homes irresponsible?

Posted: June 15, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: Alphington, Australian Conservation Foundation, Dr Robert Crawford, Fairfield, greenfield, Hugh Stretton, Ivanhoe, mcmansion, Melbourne University, Metricon Monarch, Tony Soprano, urban fringe 10 Comments Huge houses on the urban fringe are an irresponsible drain on the environment, according to this opinion piece by Dr Robert Crawford from Melbourne University. There are two charges here – one is that the average 238m2 greenfield house is too big and the other is that the occupants are too reliant on cars for transport. I discussed the transport issues related to greenfield houses recently, so this time I want to look at the allegation of excessive dwelling size.

Huge houses on the urban fringe are an irresponsible drain on the environment, according to this opinion piece by Dr Robert Crawford from Melbourne University. There are two charges here – one is that the average 238m2 greenfield house is too big and the other is that the occupants are too reliant on cars for transport. I discussed the transport issues related to greenfield houses recently, so this time I want to look at the allegation of excessive dwelling size.

There are all sorts of problems with the “too big” criticism, not least the obvious question: what is the “right” size for a dwelling? Even if that question could be answered satisfactorily, there’s another – what should be done about it? Should there be regulations limiting the size of houses? Or perhaps a “McMansions” tax? I think there’s actually a sensible way to approach this issue which I’ll come to in due course. But I want to start with some pertinent observations.

First, greenfield houses mostly aren’t as big as epithets like “McMansion” imply. When Melburnians think “McMansion” they usually have in mind a two storey house like Metricon’s 530 m2 ‘Monarch’, which is more than double the size of the average greenfield house. In the US however, the term McMansion is reserved for much, much bigger houses on very large lots like Tony and Carmela’s spread in New Jersey (see first picture). The average house on Melbourne’s fringe, however, is a much more modest 238 m2 according to Dr Crawford’s own evidence. That’s big compared to an inner city apartment but it’s much smaller than the ‘Monarch’ and much smaller than any reasonable definition of a McMansion. Further, more than two thirds of houses in Melbourne’s greenfield areas are single story. Nearly half (47%) are smaller than 240 m2. Almost three quarters (74%) are smaller than 280 m2.

Second, fringe houses aren’t much bigger, if at all, than typical houses in some older suburban areas. I live with my family 8 km from the city on the border of Ivanhoe and Alphington where most dwellings were built before WW2. Having two children who went to Alphington Primary School means I’ve seen inside many, many homes in the Alphington, Fairfield, Ivanhoe area. I can’t recall ever being in a house in these neighbourhoods that hasn’t been extended at least once in its lifetime. And while they probably were once, these aren’t small houses anymore. For example, the external dimensions of our place, including the garage (but excluding decks), is 240 m2 and it’s by no means large relative to other detached houses in the area – in fact I’d say it’s about average or perhaps even a bit smaller. Yet I don’t hear many complaints that inner suburban homes are “too big”. Read the rest of this entry »

Are apartments the answer to ‘McMansions’?

Posted: June 5, 2011 Filed under: Growth Areas, Housing | Tags: apartments, energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, houses, Melbourne University, sprawl 5 CommentsDemonising sprawl seems to be the mission of many planners, academics and journalists, but oftentimes zealotry leads to mistakes, as with this claim that infrastructure costs on the fringe are double those in established suburbs. I’m reminded again how easy it is to get the wrong end of the stick on this issue by a study released last week by the Architecture Faculty at Melbourne University.

The University’s media release tells us the study found “houses on Melbourne’s suburban fringe are responsible for drastically higher levels of greenhouse gas emissions compared to higher density housing or apartments in the inner city”. The Age ran with the media release, reporting that bigger dwellings and more car-based travel are the key reasons fringe houses consume more energy and emit more greenhouse gas than apartments.

I can’t refer you to a full copy of the study because the University didn’t make it available to the media or the public. That didn’t seem to worry The Age, but I think it’s an extraordinary decision – does the University exist to issue media releases or to undertake serious research? I contacted one of the authors who told me the study is a journal article and he couldn’t give it to me for copyright reasons. He gave me this link to the abstract. I’ve read the full article but if you don’t have on-line access you’ll have to spring for €35 if you want to read it.

A key part of the study is a comparison of the (embodied, operating and transport) energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions of households in three building types – a 100 m2 two bedroom high-rise apartment in Docklands 2 km from the city centre; a 64 m2 two bedroom suburban apartment 4 km from the centre in Windsor; and a 238 m2 detached house in an outer suburban greenfield development 37 km from the centre (the latter is shown in the accompanying chart in two versions – a 2008 five star and a “future” seven star energy rated version).

I don’t know what the point of this sort of comparison is. Putting transport aside (you’ll see why later), there’s little policy value in comparing a $1 million plus Docklands apartment with a $500,000 plus suburban apartment in Windsor, much less comparing both with a $350,000 house and land package on the urban fringe (and I’d say Windsor is inner city!). Nor does a seven square two bedroom apartment seem like a practical substitute for the sort of household that buys a 26 square four bedroom house.

A better approach would’ve been to compare the greenfield house against a townhouse of similar value located in the established suburbs, say 20 km or more from the centre (or perhaps against a greenfield townhouse set within a walkable neighbourhood). Alternatively, the authors could have followed the ACF’s lead and compared the resource use of all suburban residents with those of inner city residents – but the catch here is the ACF found that, even though on average they live in smaller dwellings, inner city residents have a higher ecological footprint (see here and here)!

The study should be on firmer ground when it compares transport energy and emissions across the three locations, but it isn’t. The trouble is the study gets it completely wrong on this key variable and, frankly, the travel findings just don’t stand up. There are two key weaknesses. Read the rest of this entry »

Is living at density the same everywhere?

Posted: May 4, 2011 Filed under: Growth Areas, Housing | Tags: fringe, growth area, housing density, outer suburbs, Public transport, town houses, walkable 6 Comments A reader, Ian Woodcock, took me to task yesterday about my post on whether outer suburban families would willingly choose densities of 25-30 dwellings/Ha so they could walk to local shops and services.

A reader, Ian Woodcock, took me to task yesterday about my post on whether outer suburban families would willingly choose densities of 25-30 dwellings/Ha so they could walk to local shops and services.

In particular, Ian reckons I invoked a straw man when I argued that “it can’t be assumed that merely increasing outer suburban housing density will create an environment with the ‘buzz’ and ambience of a St Kilda or Fitzroy”. He says the relevant comparison:

is not with inner-suburbs like St. Kilda that have the highest density in Australia (!), but with the streetcar (tram) suburbs of the inner-middle ring, like Kew, Camberwell, Malvern, Armadale, etc. where densities are higher than the outer suburbs in many places, public transport is good, there is housing diversity and access to a wide range of shops and services, and moreover, social capital is high.

Ian’s broadened the discussion beyond walkability to the merits of density more generally. I’m not sure there are substantial parts of suburbs like Camberwell with average densities as high as 25-30 dwellings/Ha, but nevertheless I’m happy to make the comparison with them. I’ve set out my argument about the attractiveness of higher densities to Growth Area residents below:

My contention is that living in a townhouse or apartment in the inner or middle suburbs – whether it be St Kilda, Kew, Fitzroy or Camberwell – delivers an entirely different set of benefits than it would in the outer suburbs. In essence, it’s worth choosing to live in a town house in the former but not at present in the latter.

Camberwell residents who can afford it generally choose to live in bigger dwellings, usually a detached house with a yard. The rest live in smaller dwellings like newish apartments and townhouses because that’s the only way they can afford to live there. They want to live in Camberwell for all the usual reasons – it’s close to the city centre, close to large centres like Glenferrie Rd and close to private schools. They also like it for the status it confers and because it’s ‘people like us’ i.e. wealthy or aspiring to be wealthy. As Ian says, it also has good public transport and a wide range of services. But most of those who live in apartments and town houses do so because they have to – it’s primarily about location, not dwelling type.

Some will argue there are people who could easily afford a big dwelling but actively prefer a small one. Undoubtedly there are some, but there aren’t many and they’re not usually families (who’re the main household type in the Growth Areas). The fact that empty nesters tend to hang on to their large houses signals that, if they can afford it, people put a high value on space. People who can afford it don’t buy studios or one bedroom apartments in Docklands or Southbank – they buy three bedroom units and penthouses. All those renovated and extended terraces and houses in the inner city don’t say “small is better”. Location and dwelling size are what economists call superior goods. As incomes rise, consumers tend to buy more of them – they might move to a better suburb or a bigger dwelling (although only the very rich can usually do both).

Now compare Camberwell to the Growth Areas. In the latter a detached house with a garden costs much the same as a townhouse. Households don’t need to forego space in order to live there, so why would they choose to buy a townhouse? Read the rest of this entry »

– Are outer suburbs dense enough to walk?

Posted: May 4, 2011 Filed under: Growth Areas, Housing | Tags: growth area, housing density, Shall we dense?, shops, walk 9 CommentsThis story in The Age says average dwelling densities in the fringe Growth Areas need to double to make walking to local shops and services viable.

It’s based on a report, Shall We Dense? (geddit?), which says the current minimum average density of 15 dwellings/Ha in the Growth Areas only yields about 510 dwellings within walking distance of local shops and services. Density needs to increase to 25-30 dwellings/Ha to provide enough residents – about 3,000 – to make local shops within walking distance viable.

I’ve said before that the downsides of sprawl are exaggerated, however if new residents of outer suburbs freely choose to live at higher densities and thereby consume less space, that’s got to be a positive step. The problem, as I touched on here, is finding the magic factor that might induce such a shift in preferences.

I don’t think that factor is being able to walk to shops. I can’t see that home buyers in the Growth Areas would actually choose to forego a big detached house and garden in order to buy, for much the same price, a considerably smaller townhouse or apartment so they could be within walking distance of a local shop or two.

I guess that really depends on what the local shops offer. But this is the outer suburbs – it isn’t Tales of the City or The Secret Life of Us. It can’t be assumed that merely increasing outer suburban housing density will create an environment with the ‘buzz’ and ambience of a St Kilda or Fitzroy. The relatively high density of activities in the inner city is sustained to a considerable degree by young, high income professionals without dependents who support all those restaurants, galleries, coffee bars and specialty services. They aren’t there by accident either – they live there because it’s close to the CBD and all those high-flying jobs and cultural, leisure and entertainment attractions. They’re prepared to downsize to get it.

The average outer suburban resident, in contrast, is likely to be married, have children, a big mortgage and limited disposable income. It’s another thing entirely for a family in the outer suburbs to downsize in order to live within walking distance of a small and expensive grocery store, perhaps with the choice of a coffee shop or a restaurant. Something this local is simply not going to have anything like the sheer number and diversity of people and outlets seen in inner city locations. Read the rest of this entry »

Are Melbourne’s houses too big?

Posted: April 20, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: Building Commission, dwelling size, empty nester, floor space, growth area, Metricon, Robie House 17 CommentsAccording to the State’s Building Commission, new houses in Victoria were 252 m2 on average in 2008-09 compared with 217 m2 in 2000-01. This report says “homes in Victoria are getting bigger, much bigger – leading to warnings that some people may be building homes bigger than they need by borrowing more than they can afford”. The Building Commissioner is quoted as saying:

The promotion of larger homes by medium and high volume builders, where added rooms are used as a marketing tool, have contributed to the increase in size……consumers are up-sold to home theatres, additional bathrooms and media rooms

I have a couple of thoughts/reactions to this.

First, some context – while there are buyers who want a behemoth like Metricon’s 49 square ‘Monarch’, almost three quarters (74%) of Growth Area buyers purchase a single level dwelling. Moreover, 70% of homes are less than 30 squares and 47% are less than 26 squares. Some are buying a “McMansion”, but most are buying something like Metricon’s Grandview.

Second, the claim that buyers are so gullible they are “upsold” to bigger homes they don’t “need” is patronising. Buyers do know what they want. Two thirds of Growth Area purchasers are buying their second home – half of this group are buying their third or fourth home. And nearly half (48%) of adult buyers in the Growth Areas are aged 35 years or more.

Third, if people are buying homes they can’t afford, that’s not primarily an issue of dwelling size. I expect over-stretched buyers would more likely be purchasing a home that’s closer to the city centre — it would be smaller than a fringe “McMansion” but cost more because of its greater accessibility. If there has been an upward movement in the proportion of people buying homes they can’t afford, the problem and the solution lie with lending policies rather than with dwelling size. Read the rest of this entry »

Will E-Gate curb suburban sprawl?

Posted: March 10, 2011 Filed under: Housing, Planning | Tags: brownfield, Denis Napthine, Docklands, e-Gate, Fishermans Bend, Major Projects, redevelopment, Richmond station, The Age, urban renewal 4 CommentsI like the (very) notional plans for redevelopment of the old E-Gate site in west Melbourne to accommodate up to 12,000 residents published in The Age (Thursday, 10 March, 2011).

Putting what might be 6,000–9,000 dwellings on 20 highly accessible hectares on the edge of the CBD makes a lot more sense than the mere 10,000–15,000 mooted for 200 hectares at Fishermans Bend.

But I do take issue with the claim by the Minister for Major Projects, Denis Napthine, that it’s a very significant development for Melbourne “because we want to grow the population without massively contributing to urban sprawl”.

The Age reinforces this take by titling its report “New city-edge suburb part of plan to curb urban sprawl” and goes on to say that it’s the first big part of the Government’s “plan to shift urban growth from Melbourne’s fringes to its heart”.

I’ve always liked the idea of E-Gate being redeveloped but, as I said on February 19 in relation to a similar report on proposals for Fishermans Bend, the significance or otherwise of the project for fringe growth has to be assessed in the context of the total housing task for Melbourne.

In the twelve months ending 30 September 2010, 42,509 dwellings were approved in the metropolitan area, of which around 17,000 were approved in the outer suburban Growth Area municipalities. That’s just for one year. E-Gate’s 6,000 – 9,000 dwellings would be released over a long time frame, probably at least ten years and quite possibly longer (the Government says Fishermans Bend will be developed over 20-30 years). Existing leases on the site run till 2014 so it’s likely the first residents won’t be moving in for a long time yet.

Of course it all helps but the contribution of the three redevelopment sites identified by the Government – E-Gate, Fishermans Bend and Richmond station – to diminishing pressure on the fringe will be modest. They don’t collectively constitute a sprawl-ameliorating strategy. Melbourne still needs a sensible approach to increasing multi-unit housing supply across the rest of the metropolitan area. The “brownfield strategy” is in danger of becoming “cargo cult urbanism”.

Who’s buying homes on the fringe?

Posted: February 7, 2011 Filed under: Growth Areas, Housing | Tags: Cardinia, Casey, first home buyers, growth areas, Hume, investors, mcmansion, Melton, Oliver Hulme, renters, Whittlesea, Wyndham 1 CommentIf you think that home buyers in the fringe Growth Area LGAs are predominantly young renters buying their first McMansion, then think again.

A survey released today by property consultants Oliver Hulme profiles home buyers in the Growth Areas LGAs i.e. Wyndham, Melton, Hume, Whittlesea, Casey and Cardinia.

Given the brouhaha in The Age today over foreign investment on the fringe, the media might give attention to the finding that 23% of purchasers in these areas are investors. However it is not possible to deduce from the report how many of them live overseas.

But there are plenty of other interesting nuggets of information.

Rather than moving out of rental accommodation and into their first home, most fringe purchasers already own a house. Only 36% are first home buyers. Of the 64% who are ‘upgrading’ from an existing owner-occupied dwelling, a third are buying their third or fourth home.

It is therefore no surprise that the average buyer is not ‘starting out’ on the great suburban journey. Nearly half (48%) of adult buyers are aged 35 years or more. In fact 14% are aged 50 or more.

And while some bought large houses, almost three quarters (74%) purchased a single level dwelling. Moreover, 70% of homes are less than 30 squares and 47% are less than 26 squares. That suggests the great bulk of dwellings are roomy but they’re hardly McMansions. However, small dwellings don’t cut it – even though 12% of buyers are single, only 1% of dwellings are smaller than 15 squares.

What’s the angle with Fishermans Bend?

Posted: December 14, 2010 Filed under: Housing, Planning | Tags: city centre, e-Gate, Fishermans Bend, high density housing, Kenneth Davidson, LA Live, Matthew Guy, Melbourne City Council, urban renewal 7 CommentsThe Minister for Planning, Matthew Guy, is reported as saying that rather than “sprinkle high density housing across Melbourne”, the new Government will give priority to strategic developments on specific sites close to the CBD.

Mr Guy has already moved to water down the former government’s planning laws encouraging higher density residential developments (i.e. over three storeys) along public transport corridors.

He says the focus of urban renewal in future will be on locations like Fishermans Bend, the 20 hectare E-Gate site just off Footscray Road, and the area around Richmond station.

This is surprisingly reminiscent of Kenneth Davidson’s prescription for Melbourne. However unlike the Minister, who is moving to increase land supply in the Growth Areas as well, Mr Davidson sees major urban renewal projects as providing enough land to obviate the need for further fringe development.

Facilitating urban renewal in areas close to the city centre is a good thing. But it’s a big call to put all your higher density eggs in one basket when Melbourne’s population is projected to grow by 1.8 million between 2006 and 2036. According to The Age, Mr Guy doesn’t want higher density development in that part of the city that lies beyond the city centre i.e. virtually all of Melbourne*.

I’m not sure the potential of the brownfields basket is as great as Messrs Guy and Davidson imagine. Here are some constraints that individually might be a mere difficulty but collectively amount to a major impediment. Read the rest of this entry »