Is News Ltd bringing discussion about cities to a standstill?

Posted: July 30, 2011 Filed under: Miscellaneous | Tags: congestion tax, Herald Sun, media bias, News Ltd, Tax Forum, The Australian 5 Comments

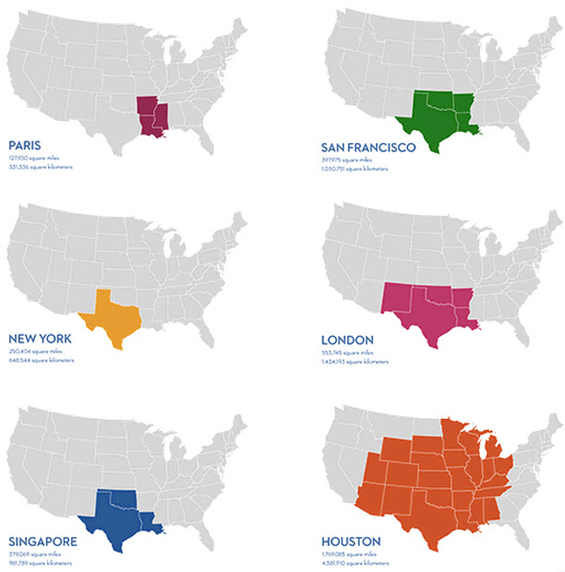

If the world's 6.9 billion people lived in a single city, how large would it be if it were as dense as.................................... (from Per Square Mile)

One of the more bizarre examples of ‘story manufacturing’ in the media I’ve seen for a while – and we regularly have some doozies – went down in News Ltd papers right across Australia on Friday.

Sydney’s Daily Telegraph ran a front-page story headlined Congestion road tax on drivers is highway robbery. The lead para told us: “workers struggling with a carbon tax are about to be hit with a second wave of Greens-inspired tax pain”. This story was repeated in News Ltd papers across the country. Melbourne’s Herald-Sun was so concerned at this imminent threat it even published an editorial on the matter, No to a new Tax – “Australians do not need another new tax”, it thundered.

And what exactly is this new tax workers are about to be hit with? Well, there’s a clue in the rest of the Herald-Sun’s (short) editorial:

Even the idea of a congestion tax, put forward by the Federal Government yesterday for discussion at the tax forum, will have taxpayers shaking their heads. Fortunately, the Gillard Government will not be able to impose this tax on top of the carbon tax, and all the other taxes Labor has brought in, because it needs the agreement of the states. A congestion tax on cars was suggested by former Treasury secretary Ken Henry to help cut petrol excise, but the taxpayers can take only so much. No, no, no.

“Even the idea”?! The incontrovertible fact is there is no new tax. All this supposed angst is manufactured from a handful of words in the Government’s new 36 page Discussion Paper released on Thursday in advance of October’s Tax Forum. The Forum is one of the conditions the independents set for their support of the Government.

The Discussion Paper canvasses a wide range of tax issues participants at the Forum might wish to discuss. These relate to personal tax, transfer payments, business tax, State taxes, environmental and social taxes, and tax system governance. At page 30, it notes the Henry Review recommended governments consider the introduction of variable congestion pricing and therefore poses the following question as a prompt for discussion:

Is there a case to more closely link road charging to the impact users have on the level of congestion on particular roads?

That’s it. It’s just a question. Moreover it’s one of 34 proposed for discussion. And so it should be – I’d be very upset if the most important prospective policy for improving the way we manage our cities wasn’t at least on the table. Read the rest of this entry »

Links for urbanists No. 1

Posted: July 28, 2011 Filed under: Miscellaneous | Tags: links, xkcd 4 CommentsAssorted links to some of the useful, the informative, the interesting, and sometimes even the slightly weird sources I stumble across from time-to-time. Worth sharing, I think:

- The level of GDP is correlated with human penis length. As xkcd often points out, correlations are easy to find.

- History of a vacant city lot. Sad and neglected now, but this lot in Philadelphia has had some wonderful buildings in its life. This is brilliant – I wish someone would do one of these for Melbourne (note to the delicate – some colourful words).

- A wolf in sheep’s clothing. Lamb is really high in carbon emissions – much worse than beef. The key problem is not enough of the carcass gets eaten.

- Why do women have to queue more at public toilets?

- Reimagining the High Street. Strategies for re-invigorating strip shopping centres decimated by the internet and big retail chains.

- Hackgate: the movie. Didn’t take Hollywood long to get on the job! Brilliant casting for the Murdoch role.

- Urban evolution. Animals in cities are adapting biologically to urban conditions.

- Opinions: most of us make it up on the spot. According to economist Robin Hanson “If you talk a lot, you probably end up expressing many opinions on many topics. But much, perhaps most, of that you just make up on the fly. You won’t give the same opinion later if the subject comes up again, and your opinion probably won’t affect your non-talk decisions”. Let me say that blogging is a discipline which makes one very conscious about being consistent because there’s always someone who’ll catch you out!

- Manhattanisation of Melbourne. Following on from my piece last week about developers using American place names, an American’s view of our cultural cringe.

- Printing with concrete. This technology makes complex shapes out of concrete using a 3D printer.

I’ll try and post more links another time.

Note the competition to win a copy of Triumph of the City closes this weekend, Saturday 30 July at midday. See sidepane for details.

Are wind turbines bad for the countryside?

Posted: July 27, 2011 Filed under: Energy & GHG | Tags: Four Corners, Mark Diesendorf, Mark Lawson, Matt Ridley, turbine, wind energy 14 CommentsEarlier this week I watched the Four Corners story, Against the Wind, on the alleged health impacts of wind turbines and came away wondering just what the point of the program was. Based on what I saw, my clear impression is there’s no issue here – there’s simply no hard evidence of the supposed health dangers of turbines*. The allegations remind me of the scare-mongering around the dangers of winds turbines to birds, which I’ve discussed before.

But I was horrified (no doubt unintentionally) by the vision of rural landscapes blighted by row upon row of giant white robots stretching along the tops of the hills. An occasional turbine is novel, even an object of beauty, but to my sensibilities a massed army of towers is a scar on the countryside.

I know they’re not being erected in pristine bushland, but the sort of sweeping pastoral panoramas in the regions filmed by Four Corners – with green meadows, stands of trees and occasional rustic buildings – are extraordinarily beautiful. It’s a different aesthetic to natural bushland, but no less valuable for that.

As if we haven’t done enough visual damage by permitting ad hoc development on the urban fringe, now we want to make the country look like Texas’s endless oil derricks. We fight tooth and nail to protect the beauty of streetscapes in the cities (admittedly not always successfully), but the defacing of farming landscapes on a grand scale goes on with hardly a murmur of protest.

It’s true we urgently need to reduce carbon emissions but I don’t think it’s obvious we need to pollute the countryside to achieve that goal. That seems a ludicrous price to pay, effectively substituting one form of environmental damage with another.

Wind isn’t the only option we have to address climate change. Wind just happens to be the cheapest form of renewable power – with subsidy – we currently have available. However that calculation doesn’t account for the long-term damage done to scenic landscapes. Just as historically we’ve done with cars, we’re failing to price the negative externalities. Read the rest of this entry »

Are too many houses empty?

Posted: July 26, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: dwellings, Earthsharing Australia, REIV, unoccupied properties, vacancy rate 4 Comments

Earthsharing Australia - Suburbs with highest proportion of properties withheld from rental market (last col)

Earthsharing Australia highlighted this week what could be a major housing supply issue in Australia’s major cities: the number of houses sitting vacant at any one time. Properties will inevitably be vacant from time to time – that’s necessary for an efficient market – but the issue is whether there are structural factors that mean too many are unoccupied for too long.

Earthsharing has attempted to quantify the number of unoccupied dwellings in Melbourne. It claims speculators are the reason why five per cent of the city’s housing stock – or 46,220 dwellings – sit empty and unrented at any time. It says the REIV’s Rental Vacancy rate is commonly referred to in media coverage as the ‘housing vacancy’ rate, but Earthsharing’s own:

Estimated Speculative Vacancy Rate (of 4.9%) is more than twice the REIV’s Rental Vacancy rate for the same period of 1.7%…….Recent increases in house prices have been driven by speculation, not a housing shortage. Property buyers are restricting the supply of housing by holding their properties off the rental market.

The Estimated Vacancy Rate for some suburbs was much higher – in Docklands it was 23% and in East Melbourne, 19% (referred to in the exhibit above as Estimated Genuine Vacancy rate).

Earthsharing’s findings are contained in a report released on the weekend, Speculative Vacancies in Melbourne 2010, which measured the number of houses (excluding the area covered by South East Water) that consumed less than 50 litres of water per day, on average, over a period of six months in 2010. The presumption is dwellings using less than this amount must be unoccupied, given that average daily consumption during the period of the study was 140-160 litres per day. The further assumption is these dwellings have been withheld from the rental market for speculative reasons.

Earthsharing’s Speculative Vacancy rate could be conservative. Unoccupied dwellings with an automatic sprinkler system or a serious leak might consume more than 50 litres per day and hence be under-counted. On the other hand, its methodology could over-count the number of unoccupied dwellings. There’s some evidence consistent with the latter view – of the 46,200 properties identified by Earthsharing as “withheld from the market”, only 15,237 consumed zero litres of water over the six month period, and hence could be regarded as unambiguously vacant.

In fact there are many reasons why a property might be occupied but nevertheless average less than 50 litres per day over six months. Apart from rental dwellings between leases, some properties are unoccupied because they’re being sold by one owner-occupier to another. There are city properties owned by country people who use them regularly but relatively briefly e.g. a weekend every fortnight. Then there are single person households who travel frequently or for extended periods, as well as “couples” where each party has their own home but they favour one.

It might be possible to refer to these sorts of properties as “under-occupied” in the same sense that empty nesters rattling around in four bedroom houses is “inefficient”, but it would be a big stretch to label them with a pejorative like speculative. These aren’t properties that are being withheld from the rental market. In short, Earthsharing’s methodology doesn’t seem very robust.

But having said that, I suspect there are far too many non-rental properties that sit unoccupied for unnecessarily long periods. Let me emphasise that I don’t have any objective data to support this contention, but if it’s right, it would add to pressure in the rental market. Consider that within 500 metres of my place (I live 8 km from the CBD) there are four properties I’m aware of that have sat vacant in recent years for twelve months or more. Read the rest of this entry »

Are neighbourhood bookshops doomed?

Posted: July 25, 2011 Filed under: Activity centres, Books | Tags: Amazon, Book Depository, books, bookshops, Crikey, internet, Readings, Zinio 18 Comments

Relative prices of selected magazines in hardcopy (1st col) vs electronic delivery in the US (2nd col) and Australia (3rd col). Chart by Kwanghui-Lim

There’s a small, independent literary bookshop in my local shopping centre whose days, I fear, are numbered. I can’t see how it will survive the online challenge. Its likely demise will make the shopping centre even more monocultural. This isn’t a big shop like Readings in Carlton, so its scope to live on by “adding value” for customers is limited.

Some people really love their local bookshops. In Friday’s Crikey, Ben Eltham said “many independent bookshops offer…..character, passion and charm”. What they provide, he says, is:

An induction into a vast and exciting secret society, populated by beautiful physical objects containing wisdom, and knowledge, and love.

Not sure I like the “secret society” bit, but as a keen reader I understand the delights of browsing, even though I don’t make a lot of use of my local bookshop. Although Readings is further away, I’m much more likely to browse there because I can combine it with a visit to the movies and dinner. Readings is also bigger with a larger range of specialised books.

However the key reason I don’t spend a lot of time in the local store is because, like most people, I’m actually far more interested in reading than I am in the act of buying. The fact is the internet offers me a vastly superior buying/browsing experience and thereby gives me more time to get down to reading.

It goes without saying that I can get books much cheaper online than I can over the local counter. There’s no way even the big chains are competitive on price with Amazon-Book Depository, so my local indie has no chance. And there’s no way any bricks and mortar bookshop in Australia can compete on stock against the online behemoths, especially when it comes to technical books or out of print volumes. A smaller bookshop can’t afford to carry all the works of even popular literary authors. Its big advantage is immediate over-the-counter delivery, but that only works if it has stock.

Then there’s information. Although I hear a lot of talk about the expertise of dedicated bookshop staff, there’s no way they can have the sort of product knowledge that’s just a click away at Amazon. Maybe bookshops run by owner-managers that specialise in arcane topics do, but chances are it’ll be something I’m not interested in. My local is a more general, literary-oriented bookshop.

Somewhere like Amazon gives you instant reviews from literary sources and other readers across the world. Amazon even tailors recommendations for new books based on your search topics and previous purchases. Even on those occasions when I do buy a book from my local (usually a gift so new releases are preferred) I’ve already done my research and know what I’m after.

If I want a novel in a hurry I’ll go to my local bookstore, but unless it’s reasonably popular or new, chances are the proprietor won’t have it in inventory. I can either get the store to order it in or do it myself at substantially lower cost (as well as avoid another trip to the store). In fact these days I’m much more likely to get an electronic copy instantly and read it on my (Kobo) e-reader. A growing proportion of Australians are doing likewise.

Some argue that if we don’t patronise our local bookshops they won’t be there when we need them. They usually turn out to be people who are in the publishing and media business, like Ben Eltham or this writer. The “use it or lose it” argument is of course rubbish – no commercial operation is likely to survive, much less flourish, on this sort of shaky business model. It would be nice to have a local bookshop but it will hardly be the end of civilisation if mine disappears – I’ve got too many other options. Read the rest of this entry »

Why is housing in European rural villages so dense?

Posted: July 25, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: Alexis DeTocqville, Cadel Evans, Castelnuovo di Garfagnana, density, Parrot and Olivier in America, Peter Carey, rural village, Tour de France 11 CommentsI can’t let the Tour de France go by without finding some way to reference this great spectacle and Cadel Evan’s singular achievement.

Something I noticed watching the Tour is how traditional French country villages have relatively high density housing compared to Australian country towns. I’ve seen the same pattern in the Italian countryside – villages of three storey (or more) apartments set within productive agricultural land.

Yet in contrast, Australian country towns are predominantly detached houses on large lots. Only the odd commercial building – like pubs – is two storeys. Why didn’t town dwellers in Australia choose to live in multi-storey buildings like Europeans?

I don’t know the answer but it’s worth thinking about and so I’m hoping someone does. There’s a host of potential explanations. It might be the car, yet parts of Australian country towns that pre-date motorisation are lower density than their European equivalents. It might have something to do with differences in the value of agriculture, yet there are some Australian towns where agriculture must’ve been of comparable or higher value than many areas of Europe e.g. wine growing regions.

Perhaps building materials were generally harder to get than in Australia – i.e. more expensive –and this encouraged smaller dwellings. Maybe the more extreme climate had an influence too, giving residents an incentive to cluster buildings for better insulation. I also wonder if there was a different tradition of village housing in England compared to the rest of Europe that was followed by early settlers in Australia.

Perhaps it was driven as much by politics as by anything else. I recently read Peter Carey’s Parrot and Olivier in America, which is loosely based on the book, Democracy in America, which French aristocrat Alexis DeTocqville wrote after touring the young democracy in the early 1830s. I was struck by the enormous gulf in the world views of the aristocracy and the common people in France at this time. So perhaps it was in the interest of the local aristocrat in country areas to maximise the amount of land in agricultural use and minimise the quantity of land and resources devoted to housing the peasants. However once the “common man” settled in the New World he could make his own choice about how much space to devote to housing and how much to agriculture.

As I say, I don’t know but I’d be interested to hear other’s views.

Why are “Tribeca” and “Madison at Upper West Side” in Melbourne?

Posted: July 21, 2011 Filed under: Miscellaneous, Planning | Tags: BoCoCa, developer, Julie Szego, Madison at Upper West Side, neighbourhood, place name, real estate, Robin Boyd, Suliman Osman, Tribeca 13 Comments

The real Upper West Side, Manhattan - apparently you can now get all of this in Melbourne, Australia (much cheaper too!)

A few months ago, writer Julie Szego bemoaned the Americanisation of place names in Melbourne. She identified two examples – the “Madison at Upper West Side” development on the old Spencer St power station site and “Tribeca” on the former Victoria Brewery site in East Melbourne.

She invoked the spirit of Robin Boyd to explain just how easy it to sell the gloss and sparkle of New York to aspirational Melburnians:

Robin Boyd in The Australian Ugliness, the highly influential polemic about cultural cringe in the 1950s and early ’60s, observed that the most ”fearful” aspect of Australia’s low-rent mimicry of the American aesthetic ”is that beneath its stillness and vacuous lack of enterprise is a terrible smugness, an acceptance of the frankly second-hand and the second-class, a wallowing in the kennel of cultural underdog”

While Melbourne’s developers and apartment buyers pretend they’re living Sex in the City downunder, real New Yorkers are continuously inventing new, home-grown names to market projects. Here are six New York neighbourhoods you probably haven’t heard of:

SoLita: Downtown Manhattan, south of NoLita between Tribeca and Little Italy

FiDi: (Financial District, geddit?) Southern tip of Manhattan between the South Street Seaport and Battery Park City

BoCoCa: Brooklyn waterfront area comprising Boerum Hill, Cobble Hill, and Carroll Gardens, also known as Columbia Street Waterfront District

LIC: Southwestern waterfront tip of Queens, including Hunter’s Point (also known as Long Island City)

Two Bridges: Southeast of Chinatown beneath the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges

Southside: South part of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, near Williamsburg Bridge exit

Other examples – some of which resurrect old names or functions – include the Meatpacking District, Dumbo (Down Under Manhattan Bridge Overpass), East Williamsburg and Vinegar Hill. According to this writer, areas “like NoMad (north of Madison Square Park) and others like SoHa (south of Harlem) haven’t exactly caught on yet”. One commenter says that some, like Dumbo, were coined by the populace, not developers.

This has all gotten too much for certain New Yorkers. Suliman Osman reports that a Brooklyn (State) Assemblyman, annoyed that real estate agents are calling the area between Prospect Heights and Crown Heights “ProCro”, is calling for a Neighbourhood Integrity Act. One of his complaints is that rebranding lower income areas as hip could ultimately displace traditional residents. Read the rest of this entry »

Are Toyota Prius drivers wankers?

Posted: July 20, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: Alison Sexton, conspicuous conservation, conspicuous consumption, Honda Civic, hybrid, Larry David, mcmansion, signalling, Steven Sexton, Toyota Prius 26 CommentsEducated elites often show distaste for the sort of conspicuous consumption exemplified by McMansions, but it seems almost everyone likes to show off, even greenies.

Two US researchers, Steven Sexton and Alison Sexton (they’re twins), have coined the term “conspicuous conservation” to describe people who spend up big to signal their green status. The standard conventions of conspicuous consumption still apply – like German cars and appliances – but now esteem can also be bought through demonstrations of austerity.

The authors set out the issue in this paper, Conspicuous Conservation: The Prius Effect and Willingness to Pay for Environmental Bona Fides:

Amid heightened concern about environmental damage and global climate change, costly private contributions to environmental protection increasingly confer status once afforded only through ostentatious displays of wastefulness. Consumers may, therefore, undertake costly actions in order to signal their type as environmentally friendly or “green.” The status conferred upon demonstration of environmental friendliness is sufficiently prized that homeowners are known to install solar panels on the shaded sides of houses so that their costly investments are visible from the street.

They examine the sorts of people who buy hybrid cars in Washington (State) and Colorado, focussing on areas with a green demographic where sales of hybrid cars are high and where ‘signalling’ green credentials therefore ought to work. They attempt to isolate the “green halo” effect by comparing sales of the market-leading Toyota Prius – which has a distinctive and unique body shape – against those of comparable hybrids like the Honda Civic. Like all of the other 23 hybrid models on the US market (excepting the Prius), the Civic is virtually indistinguishable from the bigger-selling petrol powered variants of the same car. It is only identified by a small badge and hence, unlike the Prius, fails to signal its environmental credentials.

Anyone who’s watched Larry David tootling around LA in his Prius with uncurbed enthusiasm will get the picture – “we’re Prius drivers….we’re a special breed”. As Dan Becker, the head of the global warming program at the Sierra Club says, “the Prius allowed you to make a green statement with a car for the first time ever”.

The authors cite a market research company’s finding that 57% of Prius buyers say their main reason for choosing the Prius is because “it makes a statement about me”. They refer to another study where most of the individuals interviewed had only a basic understanding of environmental issues or the ecological benefits of hybrid cars but purchased “a symbol they could incorporate into a narrative of who they are or who they wish to be”.

The authors conclude that the conspicuous conservation effect accounts on average for 33% of the Prius’s market share in Colorado and 10% in Washington. No wonder it’s come to be known as the Toyota Pious. Read the rest of this entry »

Why do the worst infrastructure projects get built?

Posted: July 19, 2011 Filed under: Infrastructure, Management | Tags: Bent Flyvbjerg, CBA, cost benefit analysis, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, project management, rail, reference class forecasting, road, Said Business School, transport 21 Comments

Inaccuracy of transportation project cost and benefit estimates by type of project, in constant prices (Flyvbjerg)

Under-estimating the cost of major infrastructure projects and over-estimating the demand is so chronic that forecasters deserve some harsh medicine, according to Professor Bent Flyvbjerg from Oxford University’s Said Business School. He says “some forecasts are so grossly misrepresented that we need to consider not only firing the forecasters but suing them too – perhaps even having a few serve time”.

Australians have plenty of experience with underperforming infrastructure projects. For starters, just in transport alone, there’s Brisbane’s Clem 7 road tunnel, Sydney’s Lane Cove and Cross City tunnels, the Brisbane and Sydney airport trains, Melbourne’s Myki ticketing fiasco, and the 2,250 km Freightlink rail line connecting Adelaide and Darwin. And they’re just the ones we know about!

Professor Flyvbjerg says cost overruns in the order of 50% in real terms are common for major infrastructure projects and overruns above 100% are not uncommon. Writing in the Oxford Review of Economic Policy, he argues that demand and benefit forecasts that are wrong by 20–70% compared with the actual outcome are also common.

Transport projects are among the worst performers (see exhibit). Professor Flyvbjerg examined 258 transport projects in 20 nations over a 70 year time frame. He found the average cost overrun for rail projects is 44.7% measured in constant prices from the build decision. For bridges and tunnels, the equivalent figure is 33.8%, and for roads 20.4%. The difference in cost overrun between the three project types is statistically significant and the size of the standard deviations shown in the first exhibit demonstrate the high degree of uncertainty and risk associated with these sorts of projects.

He also found that nine out of 10 projects have cost overruns; they happen in all nations; they’ve been a constant over the last 70 years; and cost estimates have not improved over time.

And it’s not just under-estimation of costs. Errors in forecasts of travel demand for rail and road infrastructure are also endemic. He found that actual passenger traffic for rail projects is on average 51.4% lower than forecast traffic. He says:

This is equivalent to an average overestimate in rail passenger forecasts of no less than 105.6 per cent. The result is large benefit shortfalls for rail. For roads, actual vehicle traffic is on average 9.5 per cent higher than forecasted traffic. We see that rail passenger forecasts are biased, whereas this is less the case for road traffic forecasts.

He also found that nine out of ten rail projects over-estimate traffic; 84% are wrong by over ±20%; it occurs in all countries studied; and has not improved over time.

Thus the risk associated with rail projects in particular is extraordinary. They face both an average cost overrun of 44.7% and an average traffic shortfall of 51.4%. Read the rest of this entry »

Are McMansions about class warfare?

Posted: July 18, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: Beached House, Blogger on the cast iron balcony, Club Troppo, Don Arthur, McMansions, sustainability, urban fringe 13 Comments

It's big, but who would dream of calling it a McMansion? It's Beached House, a winner in this year's Victorian architecture awards

There was a very interesting trans-blog discussion over the weekend about one of my favourites topics – McMansions. It started earlier in the month when Helen at Blogger on the Cast Iron Balcony decided to “call bullshit on the popular story that criticising McMansions is equivalent to sneering at the working class, and denying them the good things in life”. She goes on:

In this narrative, the people championing the McMansion are the true socialists and stand with the working man and woman in their quest for a truly equal society.

She reckons it’s nothing to do with class. Her alternative interpretation is that McMansions are objectively just plain bad. That’s partly, she says, because they’re shoddily built, partly because they’re environmentally greedy, and partly because buyers are unwittingly duped by advertisers and marketers into wanting these big status machines.

Don Arthur at Club Troppo picked up on Helen’s post in passing on Friday in his regular Friday Missing Links. He must’ve been intrigued by the debate because he returned on Sunday with a nice, measured commentary on the topic, Together alone, why McMansions appeal.

I’m not going to get into the detail of this debate because I’ve looked at it before (e.g. see here, here, here and here, or go to Housing in the Categories list in the sidepane for a larger selection). However I do want to summarise in twelve simple points what I think are the salient matters in this ongoing debate.

One, what we call a McMansion in Australia is modest compared to the way the term is used in the US where it originated. In the latter McMansions are palaces, but here in Australia, any outer suburban two story home and garage produced by a developer, whatever its size, seems to attract the pejorative, McMansion.

Two, only cookie cutter houses constructed by developers are McMansions. Large architect-designed bespoke detached houses like these aren’t described in such sneering, deprecating terms.

Three, the great majority of fringe dwellings don’t fit the popular definition of a McMansion. For example, in Melbourne, more than two thirds of all houses built in the Growth Areas are single story (however for some critics that means little – they implicitly regard all detached fringe houses as McMansions).

Four, buyers of McMansions aren’t from struggle town – they’re overwhelmingly 2nd and 3rd home buyers.

Five, fringe area McMansions aren’t appreciably bigger, if at all, than all those renovated detached homes within established suburbs. The latter have the advantage of larger sites, so there’s scope to extend further. When account is taken of relative household size, the difference in per capita space between McMansions and established homes – such as those occupied by empty nesters – is likely to be even smaller.

Six, there’s no evidence McMansions are more shoddily built than smaller fringe dwellings, or apartments for that matter. That’s just out and out prejudice. Read the rest of this entry »

Are young adults really dominating public transport use?

Posted: July 17, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: age, Australian Financial Review, Gen Y, passengers, patronage, Public transport 4 CommentsThe world would be a much better place if transport operators would stop spinning patronage numbers to the media and public and start giving us the salient facts instead.

The Financial Review reported on Thursday that travellers in Melbourne aged 20-29 years comprise 38% of all public transport users in the city. This figure is in line with the claim of the WA Public Transport Authority that 18-25 year olds comprise 35% of all train users in Perth and 40% of all bus users.

As I’ve indicated before, I find these sorts of figures very hard to believe, given these two cohort’s each comprise around 15% of the population. In fact they’re extraordinary. It’s true young adults have always been over-represented on public transport because many are on relatively low incomes, but it’s the sheer scale of these figures I find too good to be true.

The reality is they’re not true, at least for Melbourne. The real situation is shown in the first exhibit. According to the Victorian Department of Transport’s VISTA database, travellers in the 20-29 age group account for only 22.3% of public transport users on an average day. If confined solely to the average weekday, the figure is a little lower, 21.9%. If instead we look at public transport boardings – to allow for the possibility that young adults make more multi-modal trips than others – the proportion in the 20-29 age group using public transport is a little higher, but still only 22.9%.

That’s a long, long way short of 38%. One explanation for this evident discrepancy could be that public transport operaters are measuring something else. VISTA is a snapshot of travel on a typical day, but it could be operators are counting the number of people who have ever used public transport – even if only once or twice – in some preceding period e.g. in the previous week, month or year. This will invariably give a much higher total patronage figure than VISTA or the Census because it picks up everybody who’s used train, tram, bus or ferry at least once during the (longer) period.

If this explanation is right, it would account for why claimed patronage levels for public transport are sometimes breathtakingly high compared to the customary, more rigorous ways of measuring travel. I’ve commented before on Metlink’s use of these sorts of inflated, self-serving numbers in its marketing material, but perhaps it’s a common practise in other states too. But by itself this explanation doesn’t fully account for why the young adult cohort’s share is apparently so high relative to others (see second exhibit). Read the rest of this entry »

Some thoughts on the Myer Bourke St redevelopment

Posted: July 14, 2011 Filed under: Architecture & buildings | Tags: atrium, budget, building, Colonial, department store, design, Dianna Snape, Federation Square, Myer Bourke St, NH Architecture, retail, Roger Nelson 5 CommentsI had an interesting chat the other day with Roger Nelson, the architect whose firm, NH Architecture, designed the Myer renovation and the QV building, among others. My interest was sparked by a seminar Roger is slated to give later this month at Furnitex, the annual furniture and interiors industry expo, on the relationship between retail design, investment and commercial outcomes.

The role of architects in delivering on the triumvirate of needs – client’s, user’s and the community’s – is something I’m interested in and have written about before e.g. Is architectural criticism critical? Our main topic of discussion was the Myer Bourke St redevelopment, but this is not a review ( I’ve only spent five minutes in the new building!). Rather, I want to mention a few points that arose in our discussion I found particularly interesting. One is about the complexities of this particular project, one is about formulating the role of the building and another is about the need for more sophisticated understanding when we talk about meeting (or not) budgets.

You probably couldn’t get a better example of a commercially driven project than the Myer city store. The key players are the investors – Colonial First State and its partners – and the Myer retail chain, who’ve signed a 30 year lease on the new building. The business imperatives are straightforward: the Colonial consortium is looking for a return on the risk it’s taken on and Myer has to get and keep retail customers.

This was never going to be an easy project. For starters, Myer wanted to continue trading on site, so construction had to proceed without significantly impeding the operation of the retail business. This was also in large part a renovation, with all the attendant difficulties that working with an existing building rather than in a ‘new build’ environment implies. Successive renovations over the years have clad over the top of earlier upgrades and face lifts.

Perhaps the most daunting task was the immense responsibility of protecting and revitalising a Melbourne institution. The Myer Bourke St store is as important and visible a part of Melbourne as the footy – well maybe not that important, but it’s up there. It figures in almost everyone’s personal history in some way. It’s just part of what Melbourne is. Melburnians take a proprietorial interest in what happens to it and heaven help anyone who threatens the millions of individual biographies that include the Myer Bourke St store and all those personal ideas about what it is and should be.

A crucial idea underpinning the project teams conception of the project is that Myer is more than a store. The team saw it as a continuation of the public realm – as a place where people would go for multiple reasons, not just to shop. This vision is consistent with the project’s commercial objectives and a key way of creating it was to extend the functions of the building – for example, by restoring the heritage-listed Mural Hall and managing it for events and meetings mostly unrelated to its retail role. Another was to put windows in the top floor so that rather than the traditional department store approach of enclosure, visitors could see out across Melbourne’s rooftop landscape – a touch of Paris. And unusually for this type of building, the escalator takes visitors to the perimeter of the building on the top floor.

Then there are the smaller-scale design, layout and retail management decisions aimed at creating an attractive and generous environment. The key organising principle is the atrium, which inclines and widens as it ascends in order to gather in northern light. It offers many vantage points – visual connections and orientations – as visitors proceed upward through the changing retail offers.

A key commercial issue is how the build went against the budget. Roger isn’t hesitant in conceding the project went over the initial budget, but as always there’s much more to this sort of issue than meets the eye. One of the key questions is: which budget? Initial or final? No one really knows at the outset what a project is ultimately going to cost, especially when it involves complex unknowns like the condition of an existing building. Initial budgets are framed without perfect information and often with excessive optimism. I think an illustrative case is Fed Square – we all know it went well ‘over budget’ but what isn’t ever mentioned is how new and expensive requirements were progressively imposed on the project by the client. Read the rest of this entry »

Is inner city living the solution to obesity?

Posted: July 13, 2011 Filed under: Education, justice, health | Tags: CBD, density, exercise, health, Inner city, obesity, Public transport, suburbs 11 CommentsIt’s often pointed out that residents of the inner city, on average, are less obese than residents of the outer suburbs. Since the inner city is denser, more walkable and has much better public transport access than any other part of the metropolitan area, the conclusion seems obvious to many – a key strategy to address obesity should be to encourage higher dwelling densities and better public transport in the suburbs, especially the newer, fringe areas.

The flaw in this thinking is it fails to observe that the inner city – defined roughly as the area within 5 km of the CBD – is a different world. Relative to the suburbs, the inner city has an emphatic over-representation of younger, well educated and affluent residents with fewer dependents. The proportion of the population made up of young singles is three times that of the metropolitan area as a whole and there are twice as many young couples without children.

These are the sorts of people who on average are slimmer because they’re younger, who are of an age where appearance is enormously important, and who are well educated enough to know about nutrition and eschew fast food. They can afford to buy high quality fruit and vegetables and pay for gym memberships. Because they’re more affluent, they have fewer children on average and hence less need for a car.

They live in smaller dwellings so they can be near the CBD and take advantage of its enormous and unparalleled concentration of high-paying professional jobs, its matchless endowment of cultural attractions and its huge and diverse range of social and entertainment opportunities. There’s no other concentration of activity within the metropolitan area that comes even close to the richness of what the inner city offers.

Because they live at higher density, driving is too hard for many trips – roads are congested and parking costs range from expensive to impossible. So residents often walk or use public transport instead. That’s O.K., because they happen to live in that transit-rich, small and unique geographical area where every train line and tram line in the entire metropolitan area – the result of 130 years of construction and at least one spectacular land boom – converges.

So population density and access to public transport are not the underlying forces driving this group’s superior average BMI. Rather, it’s a combination of the small but highly specialised group who can afford to live there, on the one hand, and the special characteristics of the area, particularly the presence of the CBD, on the other.

It’s pie in the sky to imagine the sheer scale and complexity of the highly specialised attributes offered by the inner city could be replicated in the suburbs – much less the outer suburbs – within the foreseeable future. The inner city is focussed on the CBD and in almost every city in the world, the number of jobs in the city centre is an order of magnitude larger than any suburban centre (Atlanta is possibly the sole exception). In Australia, the centre offers the cream of corporate jobs.

The importance of proximity to the CBD in explaining the special character of the inner city is demonstrated by the fact walking’s share of work trips plummets from 13% in the inner city to just 2% immediately one locates in the adjacent inner suburbs. This share is only marginally better than the outer suburbs.

Will building at higher densities and providing better public transport in the outer suburbs significantly lower the incidence of obesity? Not likely. Even if all outer suburban dwellings were townhouses, the incentive to walk is much lower if there’s no CBD, cultural precinct, river, beach, historic buildings, hundreds of cafes, and hundreds of thousands of jobs to walk to. Perhaps most importantly, the outer suburbs don’t have the constraints on driving and parking that often make walking or public transport a superior alternative in the inner city. Read the rest of this entry »

Could we pay travellers not to use over-crowded trains?

Posted: July 12, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: Balaji Prabhakar, behavioural economics, Capital Bikeshare, commuting, Ella Graham-Rowe, lotteries, prizes, Public transport, Singapore, The Economist, transit 4 CommentsIf you think crowding of trains in Australia’s capital cities is bad, have a look at this extraordinary video of how they cram passengers onto trains in Japan! John West could learn a thing or two! Peak crowding is uncomfortable for passengers and increases operating costs – more capacity is needed to handle the peak, but much of it is unused in the off-peak period. That extra capacity might take many forms, such as more carriages, more trains, more staff, etc.

There could potentially be big savings if some of this peak demand were shifted to earlier or later periods. This applies to trains, buses and roads and indeed to many activities that experience peaking e.g. cinemas, concerts. Apart from the disincentive of being treated like a sardine, the standard approach is to charge a higher price in peak periods relative to the off-peak. However political constraints mean public transport operators in Australia tend to conceive of differential pricing as an off-peak concession rather than as an active way of managing peak demand.

Here’s another way of approaching this problem. The Economist reports Singapore is planning a pilot scheme offering public transport passengers a greater chance of winning a prize if they choose to go off-peak. All travellers are entered into a pool with a chance to win cash in weekly lotteries, but those who travel off-peak will effectively get three times as many ‘tickets’. The principle is that small rewards will pay for themselves in lower capital and operating costs.

The Economist quotes Stanford University academic, Balaji Prabhakar, who says lotteries rely on the behavioural-economics insight that the average person is risk-seeking when stakes are small:

Offer individuals 20p to leave the house an hour earlier, and most will say no. But a 1-in-50 chance of winning £10 may seem more enticing. The risk-seeking effect is amplified in small networks: regularly hearing about other winners leads individuals to overestimate their own chances of success.

The idea of carrots rather than sticks is not new. For example, long-standing readers might recall this proposal to reward drivers who don’t speed with a cash reward. Fines from speeders are paid into a pot and redistributed randomly as prizes to motorists who are ‘caught’ by speed cameras driving within the designated limit. The Capital Bikeshare scheme in Washington DC offers prizes to riders who travel against the dominant flow, thus reducing the cost of rebalancing the (geographical) distribution of bikes. This study of the effectiveness of a lottery in reducing car travel found it had a positive effect, although it disappeared when the lottery was stopped (note very small sample size). Read the rest of this entry »

Is it healthy to assume correlation means causation?

Posted: July 11, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic, Education, justice, health | Tags: Environment and Planning References Committee, health, Justin Wolfers, Legislative Council, obesity, physical environment, The Economist, VMT 4 Comments

Association of obesity trend in the US with vehicles miles travelled (left) and with Justin Wolfer's age (right)

The link between the physical environment and health outcomes like obesity is fraught. The Victorian Legislative Council’s Environment and Planning References Committee should bear this in mind as it goes about its new inquiry into the contribution of environmental design to public health.

The Committee might want to start with the first chart in the accompanying exhibit, which comes from a recent issue of The Economist and purports to show that obesity has increased in the US in line with the increase in miles driven over the last 15 years. The chart is based on work done by researchers at the University of Illinois who found “a striking correlation between these two variables – but with a large time lag……This near-perfect correlation (99.6%) permits predictions about obesity rates”.

Expatriate Australian economist and Wharton business school Assoc Professor, Justin Wolfers, points out the folly of this claim. It is, in his words, a “nonsensical correlation”:

When you see a variable that follows a simple trend, almost any other trending variable will fit it: miles driven, my age, the Canadian population, total deaths, food prices, cumulative rainfall, whatever.

To demonstrate his point, Professor Wolfers prepared the second chart showing an even better correlation between changes in obesity over the period and changes in his age – he didn’t even need to resort to a time lag to get such a good fit! He acknowledges The Economist offered the customary caveat that correlation does not equal causation but this chart, he says, is so completely unconvincing as to warrant a different warning: “Not persuasive enough that you should bother reading this article” (in the interests of balance, here’s The Economist’s subsequent response to Professor Wolfer’s charge).

This exchange highlights a problem with much of the research that purports to show the physical environment — particularly density and/or public transport access — has a strong effect on health-related variables like obesity. There’s plenty of evidence of correlation but not much evidence of causation. There’s no doubt obesity is inversely related to both density and access to public transport, but if it turns out these aren’t the underlying drivers of obesity then the economic cost of misdirected policies could potentially be significant.

There are special reasons why it’s hard to establish causation when dealing with real life infrastructure projects and transport/land use programs. These British epidemiologists reviewed 77 international studies examining the effectiveness of policy interventions to reduce car use. They concluded the evidence base is weak, finding only 12 were methodologically strong – and they mainly involved relatively small-scale initiatives like providing better information about travel options or direct financial incentives to reduce driving (incidentally, only half of those 12 actually worked i.e. reduced car use). Read the rest of this entry »

Glaeser’s Triumph of the City giveaway

Posted: July 10, 2011 Filed under: Books | Tags: Edward L Glaeser, Pan Macmillan, The Atlantic, Triumph of the City 1 CommentCourtesy of Pan Macmillan Australia, I have two copies of the newly released book by Edward Glaeser, Triumph of the City, to give away to readers.

This is not really a competition, it’s more of a giveaway. To enter, all you do is nominate your favourite Melbourne building, but the winners will be selected randomly.

Go to this page to enter or see PAGES menu in the side pane (don’t use this page to enter, although comments about the book are welcome here)

Edward Glaeser is a professor at Harvard and is the world’s “go to” man for research on cities. I’ve mentioned his work many times before on these pages (e.g. see here). This brief video shows him discussing Triumph of the City with The Daily Show’s John Stewart.

I read the US edition of Triumph of the City a few months ago and it’s a book worth reading and worth having. As the New York Times Reviewer wrote, you’ll “walk away dazzled by the greatness of cities and fascinated by this writer’s nimble mind”.

Here’s a “sample chapter” (it’s an adaptation but pretty close to what’s in the book) that Professor Glaeser published in the Atlantic:

IN THE BOOK of Genesis, the builders of Babel declared, “Come, let us build us a city and a tower with its top in the heavens. And let us make a name for ourselves, lest we be scattered upon the face of the whole earth.” These early developers correctly understood that cities could connect humanity. But God punished them for monumentalizing terrestrial, rather than celestial, glory. For more than 2,000 years, Western city builders took this story’s warning to heart, and the tallest structures they erected were typically church spires. In the late Middle Ages, the wool-making center of Bruges became one of the first places where a secular structure, a 354-foot belfry built to celebrate cloth-making, towered over nearby churches. But elsewhere another four or five centuries passed before secular structures surpassed religious ones. With its 281-foot spire, Trinity Church was the tallest building in New York City until 1890. Perhaps that year, when Trinity’s spire was eclipsed by a skyscraper built to house Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, should be seen as the true start of the irreligious 20th century. At almost the same time, Paris celebrated its growing wealth by erecting the 1,000-foot Eiffel Tower, which was 700 feet taller than the Cathedral of Notre-Dame.

Since that tower in Babel, height has been seen both as a symbol of power and as a way to provide more space on a fixed amount of land. The belfry of Trinity Church and Gustave Eiffel’s tower did not provide usable space. They were massive monuments to God and to French engineering, respectively. Pulitzer’s World Building was certainly a monument to Pulitzer, but it was also a relatively practical means of getting his growing news operation into a single building.

For centuries, ever taller buildings have made it possible to cram more and more people onto an acre of land. Yet until the 19th century, the move upward was a moderate evolution, in which two-story buildings were gradually replaced by four- and six-story buildings. Until the 19th century, heights were restricted by the cost of building and the limits on our desire to climb stairs. Church spires and belfry towers could pierce the heavens, but only because they were narrow and few people other than the occasional bell-ringer had to climb them. Tall buildings became possible in the 19th century, when American innovators solved the twin problems of safely moving people up and down and creating tall buildings without enormously thick lower walls. Read the rest of this entry »

What parts of Melbourne would you show to visitors?

Posted: July 7, 2011 Filed under: Books | Tags: Adelaide, Brisbane, GOMA, Kerryn Goldsworthy, Matthew Condon, UNSW Press, Wheeler Centre 15 Comments The other night my son and I had the pleasure of attending a seminar titled Emotional Cities at the Wheeler Centre, Melbourne’s wonderful cultural institution for discussion of writing and ideas. The seminar was billed, somewhat pretentiously, as an all-star line-up of literary luminaries discussing the “architecture of the mind and the cities that inspire them”. It was actually much better than that.

The other night my son and I had the pleasure of attending a seminar titled Emotional Cities at the Wheeler Centre, Melbourne’s wonderful cultural institution for discussion of writing and ideas. The seminar was billed, somewhat pretentiously, as an all-star line-up of literary luminaries discussing the “architecture of the mind and the cities that inspire them”. It was actually much better than that.

We heard moderator Louise Swinn in discussion with Matthew Condon, who’s just published a book titled Brisbane, and Kerryn Goldsworthy, who’s about to publish one titled Adelaide. These are two in a series of books on Australia’s major cities published by UNSW Press – others include Sydney (Delia Falconer) and Melbourne (Sophie Cunningham). What a great idea! Regrettably, I haven’t read any of them yet.

One of a number of interesting questions put to the panellists by Louise Swinn was what places in their cities they’d show a visitor. I’m not familiar enough with Adelaide to appreciate Kerryn Goldsworthy’s picks, but I know Brisbane very well. Matthew Condon said he’d show his visitors Brisbane’s Southbank, starting with the new Gallery of Modern Art, moving through the various buildings in the cultural precinct and on to the pools and palm trees opposite the CBD.

This is an interesting way to think about any place. I concur with Matthew Condon. When I lived in Brisbane in the 90s Southbank was a “must see” for visitors – I thought of it as “the people’s five star resort”. The superb GOMA has made it even better and while there I’d throw in a visit to the nearby Grey Street and Roma Street railyards redevelopments. In my view almost any part of inner city Brisbane is worth seeing for those magnificent ridge lines, timber bungalows and fecund sub-tropical gardens. Even the standard of new building and urban design is generally very good.

Yet notwithstanding Brisbane’s wonderful natural and human-made assets, it seems it might still lack something vital for Gen Ys. We recently had a new graduate from Brisbane stay with us for a few weeks. She told us she knew of seven other Brisbanites in their early 20s who’d also moved to Melbourne from the north around the same time. What’s particularly interesting is they’ve ignored the siren call of Sydney, the traditional “greener pasture” for young Brisbanites. It’s about jobs, culture and buzz – Melbourne’s got it, Brisbane hasn’t. Nor, it seems, has Sydney. (And yes, one should be careful extrapolating from the particular to the general!).

What to show a visitor in Melbourne? That will depend on who you are and who they are. Children make an enormous difference to tastes and practicality, as does the age and interests of your visitors. Our Gen Y friend is likely to have different tastes from some of my baby boomer friends. But there are some universals, like the harbour and opera house in Sydney. Read the rest of this entry »

Do as many Melburnians cycle to work as Americans?

Posted: July 5, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: Aaron Renn, bicycles, commuting, Cycling, Kory Northrop, Melburnian, mode share, Nancy Folbre, Portland, Portlander, Portlandia, The Urbanophile 7 CommentsThis remarkable map, via Nancy Folbre, shows cycling has a non-trivial share of commuting in at least ten cities in the automobile-centric USA. In Portland OR, 6% of workers commute by bicycle and in Minneapolis 4%. Cycling’s mode share is 3% in Oakland, San Francisco and Seattle, and 2% in Boston, Philadelphia, Washington DC, New Orleans and Honolulu.

How does Melbourne compare with US cities? These ten cities are central counties so there’s no point in comparing them with the entire Melbourne metropolitan area (where bicycle’s share of commutes is 1%). In order to arrive at a fair basis for comparison, it’s necessary to look at bicycle’s share of commutes in Melbourne’s inner city and inner suburbs.

So I’ve summed the Statistical Subdivisions of Inner Melbourne, Moreland, Northern Middle Melbourne and Boroondara. They give me a combined area – which I’ll call central Melbourne – of 313 km2 and a total population of 804,112. That’s a little smaller geographically than Portland, which occupies 376 km2, but it’s a much larger population than Portland’s 566,143.

Cycling’s share of commutes in central Melbourne is 2.81%, which seems pretty good compared to most US cities. However given it’s substantially higher population density, it’s surprising that central Melbourne falls well short of Portland, where 5.81% of commutes are by bicycle. Some allowance has to be made for different methodologies – for example, the Portland figures are 2009 and the Melbourne figures are from the 2006 Census – but that’s not enough to explain a gap this size.

My family and I spent a week in Portland in 2009 and I don’t recall any obvious physical differences that favour cycling relative to Melbourne. In fact at first glance Portland doesn’t look especially promising for bicycles. It’s hillier than central Melbourne, it’s colder and it’s lower density. I doubt that Portland is better endowed than central Melbourne with commuter-friendly cycling infrastructure either.

In some ways Portland actually belies its status as the darling of new urbanism. It’s spaghettied with freeways and in many places doesn’t have footpaths. Even with the new light rail system, public transport has a substantially lower share of travel than in Melbourne.

I think a better explanation for cycling’s high commute share is the special demography of Portland. Aaron Renn puts it this way:

People move to New York City to test their mettle in America’s ultimate arena. They move to Silicon Valley to strike it rich in high tech. But they move to Portland for values and lifestyle; for personal more than professional reasons; to consume as much as produce. People move to Portland to move to Portland.

He cites Joel Kotkin, who reckons “Portland is to today’s generation what San Francisco was to mine: a hip, not too expensive place for young slackers to go”. I like the way the comedy TV show Portlandia put it, describing Portland as the place “where young people go to retire”. Read the rest of this entry »

Is exempting petrol from the carbon tax such a big problem?

Posted: July 4, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic, Energy & GHG | Tags: carbon price, carbon tax, CSIRO, emissions, exemption, greenhouse gas, Productivity Commission 9 Comments

Is transport the main game? Source: Productivity Commission: Carbon emission policies in key economies

Given Australia already has a large excise tax on petrol, exempting automotive fuel bought by “families, tradies and small businesses” from the Gillard Government’s carbon tax is not the disaster some would have us believe.

Australia has a minority government so compromise was inevitable – two of the independents, Tony Windsor and Rob Oakeshott, wouldn’t be party to any increase in the price of fuel for their country constituents. It was either put a price on most but not all sources of greenhouse gas, or have the whole idea shot down yet again.

The exemption is expected to apply to petrol, diesel and LPG. Were the tax to apply to petrol, the impact would be modest – a $25/tonne tax is generally estimated to increase the price at the pump by around $0.06 per litre. The CSIRO calculates that even a $40/tonne tax would only raise the price of petrol by about ten cents per litre.

These amounts are much less than motorists already pay via the $0.38 per litre excise tax on petrol and diesel (there’s no excise on LPG). While it might have a “sin tax” dimension in relation to cigarettes and alcohol, in the case of automotive fuel the excise is not aimed at making motorists pay for roads or for the external costs of petrol – it’s just a convenient way of raising revenue (although it’s not as good as it used to be since John Howard abolished automatic indexation of the price in 2001).

Nevertheless the excise tax is a serious deterrent to driving. The Productivity Commission’s recent report, Carbon emission policies in key economies, calculates that “in 2009-10, fuel taxes reduced emissions from road transport by 8 to 23 percent in Australia at an average cost of $57-$59 per tonne of CO2-e”. Although not put in place with the purpose of abating emissions, the excise already has a much more significant effect on driving than any level of carbon price that’s been seriously touted in the political debate. Based on the CSIRO’s estimates, it could be argued its effect is equivalent to a carbon tax of over $100 per tonne (the relationship isn’t linear – there’re diminishing returns from a marginal increase as the fuel tax gets bigger).

Thus there’s a good argument that automotive fuel is one of the few areas where consumers already pay a high level of tax over and above the GST. Indeed, if it were so minded, the Government could’ve imposed the new carbon tax on petrol and diesel and simply provided an equal offsetting reduction in the level of the existing fuel excise tax. There wouldn’t be a lot of political or economic sense in that, but it illustrates the principle. Read the rest of this entry »