Where are architects going with housing?

Posted: June 30, 2011 Filed under: Architecture & buildings, Housing | Tags: A'Beckett Tower, AIA, Architects Institute Australia, architecture, awards 2011, BKK Architects, Elenberg Fraser, Hayball, Muir and Mendes, NMBW Architecture Studio, Sally Draper Architects 9 Comments

A'Beckett Tower - Winner 2011 Victorian Architect's Institute Award for multiple residential (two bed unit)

Victoria’s architects had their annual awards ceremony last Friday, handing out gongs in a range of categories. Curiously, the official AIA site shows the happy faces of the winning architects, but no pictures of the winning buildings. It should have both! Nevertheless, I finally succeeded in locating a file showing pictures of all the winning buildings in all categories – see Award Winners 2011.

Given the pressing housing issues facing our cities – like declining affordability and the need for higher densities in established suburbs – I was curious to see what the best architects in the State were doing in housing design, so I took a look at the winners in the New Residential Architecture category.

The premier honour for residential architecture in Victoria – The Harold Desbrowe-Annear Award – was won by NMBW Architecture Studio for a house in Sorrento. This is a detached house on a relatively large lot. In fact it could be is an up-market beach house.

There were three other winners in the New Residential category. Two of them – Beached House, by BKK Architects, and Westernport House, by Sally Draper Architects – are also detached houses in relatively remote (from Melbourne) locations, seemingly on even larger lots.

The only winner located in a metropolitan setting is the Law Street house, built for their own use by husband and wife architects, Amy Muir and Bruno Mendes. I like it, but architect’s own houses don’t generally provide a template for addressing the wider task of housing the population at large.

In contrast, there were only two awards for higher density housing. The premier Best Overend Award for Multiple Residential went to architects Elenberg Fraser for the A’Beckett Tower (see exhibits) and the other to Hayball architects for a three storey development in John Street, Doncaster. Read the rest of this entry »

Are SUVs killers?

Posted: June 28, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: arms race, Maximilian Auffhammer, Michael Anderson, NBER, Pounds that kill, safety, SUV, traffic accident, traffic fatalities, vehicle weight 7 CommentsMy hate-hate attitude towards SUVs hasn’t improved after reading a new US research paper, The pounds that kill, by two University of California (Berkeley) researchers. They show being in a vehicle struck by a 1,000 pound heavier one results in a 47% increase in the probability of a fatality in the smaller vehicle (the paper might be gated for some – here’s an ungated version that looks very similar).

The authors note that from 1975 to 1980, the average weight of US cars dropped from 4,060 pounds to 3,228 pounds in response to higher petrol prices. However average vehicle weight began to rise as petrol prices fell in the late 1980s and by 2005 it was back to the 1975 level. In 2008 the average car was about 530 pounds heavier than it was in 1988.

A key reason for increasing weight is the safety “arms race”. Drivers seek large vehicles because they’re thought to be much safer for occupants than smaller ones, however they are more hazardous for other travellers in smaller vehicles. As the average size of the fleet rises, there’s an incentive for all drivers concerned about safety to trade-up. The authors note the “safety benefits of vehicle weight are therefore internal, while the safety costs of vehicle weight are external”.

Safety is a key public policy issue because road accidents are as dangerous to life as lung cancer. Moreover, traffic accidents kill more Americans aged under 40 years of age than any other cause. While only as quarter as many people die on roads each year as die from lung cancer, the average age of a road accident victim is 39 years compared to 71 years for lung cancer. The aggregate years of life lost from both causes is similar.

Noting that no detailed attempt has been made to measure the external costs of vehicle weight, the authors sought to:

quantify the external costs of vehicle weight using a large micro data set on police-reported crashes for a set of 8 heterogeneous states…..The data set includes both fatal and nonfatal accidents…..The rich set of vehicle, person, and accident observables in the data set allow us to minimize concerns about omitted variables bias.

They estimate a 1,000 pound increase in striking vehicle weight raises the probability of a fatality in the struck vehicle by 47%. Moreover, they find that light trucks like SUVs, pickups and minivans “raise the probability of a fatality in the struck car – in addition to the effect of their already higher vehicle weight”. The authors suggest this additional effect could be due to the stiffer chassis and higher ride height of light trucks, or possibly to the behaviour of light truck drivers. Read the rest of this entry »

Does concern for the environment drive public transport patronage growth?

Posted: June 27, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: ATRF, Department of Transport, environment, fitness, health, Meltlink, patronage, Public transport, Simon Gaymer, Victoria 7 CommentsAccording to a recent paper, research by the Victorian Department of Transport (DoT) suggests concern for the environment and a healthy lifestyle is a key driver of the recent surge in public transport patronage in Melbourne.

DoT initially concluded that the primary drivers of growth over the period 2002-07 were population growth, higher petrol prices and growth in CBD jobs (see exhibit). Neither traffic congestion nor public transport service quality appeared to play a significant role.

However a large proportion of the patronage increase on trains – equivalent to about 40,000 extra daily passengers – was not explained by the variables and/or the elasticities that DoT assumed in its modelling. This unexplained increase is labelled “Other factors” on the exhibit.

Some research undertaken by Dot and Metlink suggested it might possibly relate to attitudinal factors. Of the top eight reasons given by respondents for reducing their vehicle use, environmental concerns and health & fitness ranked equal second behind petrol prices, but ahead of parking costs.

DoT subsequently undertook a telephone survey of 1500 Melburnians aged over 16 years, asking them about their attitudes to travel options and their existing travel patterns. Using cluster analysis, the researchers identified six main “attitudinal segments”:

Public transport lifestylers (19%) – “Using public transport as much as possible is just the right thing to do. Apart from being a part of my basic day to day life, it has the advantage of being better for the environment when compared to other transport modes”

Public transport works for me (17%) – “I value the time I spend on public transport. I get things out of using public transport that I wouldn’t with other modes”

Public transport rejecters (18%) – “I wouldn’t use public transport even if it was free”

Car works for me (16%) – “Car is the most convenient and useful way for me to get around. It’s not that I have a big problem with public transport; it’s just that it doesn’t suit me as much”

Agnostics (15%) – “I’m just not all that interested in the matter of how I get around. Some people are car people and some like public transport, but I’m not overly fussed either way. If you changed the public transport system, I probably wouldn’t even notice”

Convertibles (15%) – “I use my car mainly but am actually pretty open to using public transport more….but it will need to improve before I do”

Thus according to this research, nearly a fifth of Melburnians are now Public transport lifestylers who “align themselves with public transport due to a strong belief in environmental and sustainability issues, as well as a desire to live a healthy lifestyle”. What’s surprising is that all six segments have almost no (significant) relationship with age, gender, income, education or distance from the CBD e.g. the large Lifestylers segment is not just made up of inner city Greens voters.

While respondents in this segment don’t necessarily all use public transport, the paper concludes that “the results strongly point to attitudinal change having played a significant role in recent patronage growth”.

I’d like to, but I don’t buy the implication that this attitude is a major independent driver of patronage growth. My interpretation is that there’s a cluster of people who have green attitudes and not surprisingly also have a positive attitude to public transport. But I don’t think they’d use public transport in significantly greater numbers if it took longer or was more expensive than the alternatives. They’d use public transport for the same reasons most people do – because for some trips it’s cheaper and/or faster than the alternatives. Read the rest of this entry »

What type of housing do we prefer?

Posted: June 25, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: apartment, detached house, Grattan Institute, Housing, preferences, stock, The cities we need, The Housing We'd Choose, town house 6 CommentsThe Herald-Sun reported last week that “the great Australian dream of owning a home on a quarter-acre block might no longer exist. Instead, Australians want more town houses and apartments in the more desirable areas”.

The important words are the last five – “in the more desirable areas”. Australians still love their big, detached houses but they also value location. The baby boomers could have a detached house on the suburban fringe and still have reasonable access to the rest of the city, but those days are vanishing. Now, people who want to live in an accessible location increasingly have to forgo space and accept a smaller dwelling, often a town house or apartment. As illustrated here, those leading this trend are young, small households without dependents – they’re less sensitive to space than families and place a higher value on density.

The Herald-Sun’s interest in this issue was sparked by a new study by the Grattan Institute, The Housing We’d Choose, on the housing preferences of residents of Sydney and Melbourne. It shows that more than half of households in these cities would rather live in a multi-unit dwelling in the right location than in a detached house in the wrong location.

This presents a serious problem for policy – the existing stock of housing no longer matches up with resident’s changing preferences. The Institute finds that a whopping 59% of Sydneysiders and 52% of Melburnians would prefer some form of multi-unit living. Yet this type of dwelling makes up only 48% and 28% respectively of the existing housing stock in the two cities (see first exhibit). Moreover, in Melbourne, developers are continuing to under-provide medium and higher density housing, leaving households with little choice other than to live in sub-optimal locations, albeit in a detached house.

I must admit I was disappointed with the Grattan Institute’s first report in its Cities series, The Cities We Need, so I wasn’t expecting a lot from The Housing We’d Choose. It’s not that there was anything technically wrong with the first report, it’s just that it seemed a curiously pointless exercise – as I noted here, it’s so high-level it didn’t take the debate on urban issues anywhere or advance the cause of better policy.

This time however the Institute has applied all those brains and resources to a meaty and relevant issue and, moreover, gone about it in a logical and determined way. While The Housing We’d Choose has some flaws, it shows up the limitations of the research being churned out by some of our local universities and lobby groups. This is the kind of study they should be examining closely.

The headline finding – that people are prepared to trade off dwelling size and type for greater accessibility – may seem self-evident, but the Institute has attempted the important task of measuring this preference. The researchers sought to simulate real life. They gave a sample of households in the two cities a range of real location, housing type and dwelling size options and asked them to make trade-offs in order to arrive at their preferred combination. The smart thing is the trade-off was constrained by real-life prices and the real incomes of respondents. Read the rest of this entry »

Is bike-share the safest way to cycle?

Posted: June 23, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: accidents, Capital Bikeshare, Cycling, Melbourne Bike Share, safety, Streetsblog, Velib 5 Comments

Abbott recants and embraces a tax on carbon - "if you want to put a price on carbon why not just do it with a simple tax?"! The Melbourne Urbanist is not politically partisan, but gives credit to any politician who shows this sort of courage! (wow, the things they can do these days with a bit of smoke and a few mirrors! Remarkable)

According to this story, riders of share-bikes are involved in fewer accidents and sustain fewer injuries than cyclists who ride their own bikes. The author provides an impressive array of examples.

In Paris, Velib riders account for a third of all bike trips but are involved in only a quarter of all bike crashes. In London, the first 4.5 million trips on the new “Boris bikes” resulted in no serious injuries, whereas the same number of trips on personal bikes injured 12 people. The situation in Boston DC is similar:

In its first seven months of operation, Capital Bikeshare users made 330,000 trips. In that time, seven crashes of any kind were reported, and none involved serious injuries. In comparison, there were 338 cyclist injuries and fatalities overall in 2010, according to the District Department of Transportation, with an estimated 28,400 trips per weekday, 5,000 of which take place on Capital Bikeshare bikes.

So it seems likely that Melbourne Bike Share’s unloved Bixis are at least a safer way to travel than ordinary bicycles. The implication of the story is that upright bicycles may be safer than the racers and mountain bikes we’re used to in Australia. That might sound plausible on first hearing, but I’m not so sure.

What strikes me straight up about these numbers is that relative trip rates don’t provide a valid basis for comparison. The only sensible measure is “accidents per km” because it indicates the relative exposure to potential accidents. Share-bike riders pay more the longer they rent the bike, so they have an incentive to take relatively short trips. On the other hand, I think it’s very likely personal riders travel longer distances – e.g. for commuting or leisure – and accordingly have greater exposure to potential accidents.

That doesn’t “disprove” the claim that share-bikes are safer than ordinary bikes, it just says the quoted statistics don’t tell us if they are or they aren’t. But for the sake of argument, let’s suppose share-bikes are safer, even if the difference is less dramatic than the quoted numbers suggest (intuitively, I suspect they actually are a bit safer on a per km basis). But if so, what is the underlying reason? Is it some intrinsic quality of share-bikes? After all, they’re heavier and therefore slower than ordinary bikes so that might explain it. Another reason might be their more upright riding position, which makes them more visible to motorists.

These explanations could have some role, but I think there are more obvious reasons why share-bikes might have a lower accident rate (if in fact they actually do). Read the rest of this entry »

Is this the end of The Age (as we know it)?

Posted: June 22, 2011 Filed under: Miscellaneous | Tags: Australian Financial Review, Banyule & Nillumbik Weekly, Business Spectator, Crikey, Fairfax, Greg Hywood, media, newspaper, online, Ron Walker, Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, The Weekly Review 7 CommentsMy family let our subscription to The Age lapse the other week. It’s not that $419 p.a. isn’t good value – we’d be prepared to pay a bit more if we had to – it’s just that no one in the household reads the print edition of the paper anymore. And we no longer have to pay anything to read The Age electronically!

My wife has a free six months subscription to the iPad version and I read the free online version. More often than not, the home-delivered paper version never got unrolled. So when the decision came to renew for another year there was no point in pouring another $419 down the drain.

Maybe if the circulation department had followed up with a sweetener we might’ve changed our mind out of habit or because the idea of not reading The Age every morning over coffee and croissants is ‘unMelburnian’. But the company didn’t seem overly bothered about losing us (unlike, for example, lean and nimble Crikey, who worked harder at getting me to resubscribe).

Fairfax is having serious problems with its papers. As I understand it, the Sydney Morning Herald is on the verge of going into the red and The Age isn’t far behind. For Melburnians, there is a high probability that The Age as we know it will disappear from newsstands sooner rather than later.

The problems for Fairfax, the company that owns these papers, started with the enormous drop in revenue from classified advertising. These were rightly called “rivers of gold”. Older Melbourne readers might remember the advertising slogan “icpota” (“in the classified pages of The Age”). Fairfax wasn’t very successful in adapting to the online world – companies like car.sales.com, seek.com and eBay stole its market dominance. Nor does the company seem much better today – only last year my Fairfax-owned local paper, the Banyule & Nillumbik Weekly, was blindsided by a newcomer, the Weekly Review, which took over virtually all its real estate advertising. This week the Fairfax paper is 20 pages (with one half-page real estate ad), the Weekly Review is 96 pages (with 79.5 pages of real estate ads).

Another problem for Fairfax is the well known shift of readers (like me) to online media. The company feels it has to have an online presence to “stay in the game” yet it’s too nervous to put up a paywall for fear it will lose readers to other online sites that stay free. It’s earning modest revenue from (awfully intrusive!) online advertising, but Fairfax’s experience with putting its third paper, the Australian Financial Review, behind a paywall hasn’t been positive. The AFR lost visibility because it couldn’t be accessed by search engines, giving newcomers like the online Business Spectator a free kick. From what I can gather, the financial situation of the AFR isn’t healthy either.

New Fairfax CEO Greg Hywood has a plan to turn around the ailing fortunes of Fairfax’s three major newspapers (BTW, Fairfax also owns other assets e.g. 3AW). It seems he’s proposing to put all three online papers behind a semi-permeable paywall where most content is free, but premium content requires payment. This approach would allow search engines access to the site but still leave scope to earn revenue from subscriptions. The New York Times recently moved in this direction – it offers 20 free views per month before requiring a subscription (although if you come to the Times by clicking a link on someone’s sites that doesn’t count toward your 20). Read the rest of this entry »

Does business oppose congestion charging?

Posted: June 21, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: Acil Tasman, BITRE, congestion charging, road pricing, VCEC, VECCI 15 CommentsI’m very disappointed with the line one of the State’s largest employer associations, VECCI, is taking on road congestion charging. This issue was raised in a report prepared by consultants Acil Tasman for the Competition Commission’s (VCEC) inquiry into a State-based reform agenda.

Congestion imposes such a high cost on business – whether freight or personal business travel – that I’d expect the great majority of VECCI’s members would be better off with pricing. The Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics puts the current cost of congestion in Melbourne at around $3 billion per year, rising to $6.1 billion by 2020 with unchanged policies.

VECCI says it is opposes the idea of congestion charging for three reasons. First, motorists already pay both the CBD Congestion Levy and the fuel excise. Second, there’s no spare capacity in the public transport system to take displaced motorists. Third, the economy can’t handle another tax on top of the forthcoming mining tax and the carbon price.

In regard to VECCI’s first objection, the obvious point is that these existing imposts on motorists aren’t working – many Melbourne roads are still congested at peak times. Despite the lofty title, the CBD Congestion Levy is actually a tax on parking. It’s only had a very minor impact on traffic because most drivers don’t pay it personally – their employers do. It isn’t in any event peak-loaded and of course it does nothing to manage the level of through traffic. And as per the name, the levy only applies to the CBD. The $0.38 fuel excise tax (no longer indexed) does reduce the overall level of travel by motorists, but has no appreciable effect on congestion because it doesn’t vary with the level of traffic or time of day.

So far as the “no spare capacity on public transport” objection is concerned, a congestion price only has to remove a relatively small number of vehicles in order to get traffic moving at an acceptable speed. The vast majority of motorists won’t come seeking a seat on the train – they will continue to drive but, rather than pay with time as they do at present under congested conditions, they’ll pay in cash. Their numbers may increase over time, but so will public transport capacity. Also, revenue from congestion charging should be applied to improving public transport and increasing capacity.

VECCI’s argument that the economy can’t handle another tax is about as nakedly political as you can get. Australia is one of the world’s most vibrant economies and has been growing for 20 years. Motorists, both business and private, can afford to pay their way. In any event, a congestion charge isn’t a tax — as the name says, it’s actually a charge. Motorists pay directly for the quantity of road space they use and get a direct and immediate benefit – faster travel. That means motorists who travel more pay more. It also benefits drivers from all income strata by enabling them to reduce delays when they make high value trips. Read the rest of this entry »

Are current carbon policies cost-effective?

Posted: June 20, 2011 Filed under: Energy & GHG | Tags: biofuels, electricity generation, ethanol, greenhouse gas abatement, Productivity Commission, solar photovoltaic 5 CommentsThe Productivity Commission’s new research report, Carbon emission policies in key economies, has important implications for the way emissions are managed, but it also has some key lessons for urban and transport policy (and other areas of policy, for that matter).

The report should remove any doubt that a price on carbon is far and away the most efficient and least-cost means of reducing emissions. The report’s findings are damning of so-called direct action policies and make it clear that “the abatement from existing policies could have been achieved at a fraction of the cost” if a carbon tax or emissions trading price were in place.

The Commission estimates Australia’s key supply side programs to reduce emission in the electricity sector — principally Renewable Energy Targets and solar feed-in tariffs — cost on average $44-$99 per tonne of CO2 abated. Electricity generated from solar photovoltaic cells is very expensive, costing between $431 and $1,043/t CO2 and contributing little to overall emissions reduction.

But here’s the money shot – the Commission calculates that the same level of carbon abatement produced by these supply side measures could have been obtained with a $9/tonne price on carbon! The report goes on:

This equates to about 11 per cent of the almost A$500 million estimated cost of the existing policies. Alternatively, for the same aggregate cost, more than twice the abatement could be achieved. One of the reasons an explicit carbon price would be expected to be more cost effective at such low levels of abatement is that, as modelled, it captures a considerable amount of low-cost abatement on the demand side.

The research also examined the use of bio-fuels in the transport sector. The implicit cost of carbon abatement from existing bio-fuels programs, both in Australia and overseas, is much higher than it is for electricity generation. The Commission estimates the cost of programs in Australia is $364/t CO2 but it is $600 – $700/t CO2 in Japan and the USA. It’s estimated that it is costing $6,105 to abate a tonne of CO2 in China using ethanol.

The accompanying exhibit illustrates notionally how Australia – and the other countries examined by the Commission – are tending to favour high cost abatement initiatives (the shaded bars) and ignore others that cost less per tonne and mostly yield more abatement.

Regrettably, there are many parallels with the way we go about designing policy for our cities. For example, I think it would be much more cost-effective to abate carbon (or reduce oil consumption) in the urban passenger transport sector by introducing policies such as road pricing or more fuel-efficient vehicles, than it would be to (say) build a rail line to Doncaster. Or, were the objective to increase the mobility of those without access to a car, spending funds on buses and better service coordination rather than on extensions to the rail network, would give a more cost-effective outcome.

The good news though is there might be grounds to be optimistic that PV module prices are starting to fall.

Who lives in the city centre?

Posted: June 19, 2011 Filed under: Housing, Planning, Population | Tags: apartments, Core, demography, Inner city, Maryann Wullf, Michele Lobo, migration, Monash, overseas students 11 CommentsThere’s so much misinformation being put about lately regarding apartments and city centre living that I thought it would be timely to put some basic facts on the table. Fortuitously, I recently came across a paper by two academics from the School of Geography and Environmental Science at Monash University, Maryann Wullf and Michele Lobo, published in the journal Urban Policy and Research in 2009. It’s gated, but the tables I’ve assembled summarise most of the salient findings.

The authors examine the demographic profile of residents of Melbourne’s Core and Inner City in 2001 and 2006 and compare it against Melbourne as a whole i.e. the Melbourne Statistical Division (MSD). They characterise the Core as “new build” (60.6% of dwellings are apartments three storeys or higher) and the Inner City as “revitalised”.

The Core is defined as the CBD, Southbank, Docklands and the western portion of Port Phillip municipality i.e. Port Melbourne, South Melbourne and Middle Park. They define the Inner City as the rest of Port Phillip and Melbourne municipalities, plus Yarra and the Prahran part of Stonnington municipality. So what did they find? (but let me say from the outset that the implications and emphasis in what follows is my interpretation of the data, rather then necessarily theirs).

A key statistic is that the share of Melbourne’s total population who live in the Core is extremely small – just 1.7%. So however interesting the demography of the Core might be, it represents just a fraction of the bigger picture and accordingly we need to be very careful, I think, about assuming what goes on there reflects what the other 98.3% of Melburnians think, want or are doing. And the same goes for the Inner City, which has just 5.9% of the MSD population.

When the authors looked at the age profile of the Core they found it is astonishingly young. The proportion comprised of Young Singles and Young Childless Couples is an extraordinary 44.0%. The corresponding figure for Melbourne as a whole (i.e. the MSD) is 15.1%, or about a third the size. And just to emphasise the point of the previous para, note the Core has 26,486 persons in these two categories, whereas the MSD has 542,481.

Households in the Core also tend to be small with only 21.6% having children. In comparison, the MSD might as well be another country – the corresponding figure is 53.3%. Unfortunately the researchers don’t break down the large Young Singles group by household size, but given the predominance of apartments in the Core, it’s a fair bet they tend to live in one and two person households.

I expect it will surprise many to see that Mid-life Empty Nesters make up much the same proportion of the population in the Core (and Inner City) as they do in the MSD. They’re also a small group – they account for just 8.3% of the population of the Core and hence their impact on the demography of the city centre is really quite modest. Read the rest of this entry »

Do we still need to conserve water?

Posted: June 16, 2011 Filed under: Infrastructure | Tags: conservation, desalination, Doncaster rail, Hoddle Street, pricing, sewage, water, Yarra Valley Water 10 Comments

The Silk Road - one of 108 Giant Chinese Infrastructure Projects that are reshaping the world (click to see rest)

It seems the water conservation message is starting to recede as the Government and water authorities come to grips with the breaking of the drought and the oceanic task of paying for new infrastructure like the desalination plant and north-south pipeline. Some small evidence of this trend is evident from the latest invoice my household got from our water retailer, Yarra Valley Water.

Our consumption for the three months to 25 May was 626 litres per day. The invoice has the familiar graphic showing how to convert household consumption to per capita consumption, but there’s no longer any target to compare your performance against. We consumed 157 litres per day per person but there’s nothing to help make sense of that number. Unless you can recall the now-abandoned daily target of 150 litres per person, you won’t know if you’re consuming too much water or too little.

The other thing is water consumption charges still account for only a small proportion of the bill – in fact our 626 litres make up slightly less than a third of the total amount. The rest of it is made up of standing costs for “drainage”, “sewage” and “service” charges, which customers have no real control over*. So even if we worked harder at reducing our consumption, the financial pay-off would be pretty small. The pricing of water continues to offer little incentive for conservation, a point I made nine months ago.

Discouraging water use is now a financial liability for the Government and water authorities. They’re in deep water primarily because the former Government had a political problem – it needed to show it wasn’t out of its depth but had a plan to deal with the drought. But rather than navigate the politically troubled waters of low-cost measures like stronger conservation incentives (for example, by raising water prices) it did what governments usually do – spend big licks of money and rely on the costs being diffused over time across large numbers of customers.

This pattern of spending rather than managing is pretty much standard practice for governments. We currently have the possibility of immense sums being spent to address the congestion and capacity problems of Hoddle Street, when the vastly more efficient solution would be to price access to roads. We have the more likely prospect of even bigger sums being spent to construct a rail line to Doncaster when effective public transport can be provided by bus at much lower cost. Read the rest of this entry »

Are huge homes irresponsible?

Posted: June 15, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: Alphington, Australian Conservation Foundation, Dr Robert Crawford, Fairfield, greenfield, Hugh Stretton, Ivanhoe, mcmansion, Melbourne University, Metricon Monarch, Tony Soprano, urban fringe 10 Comments Huge houses on the urban fringe are an irresponsible drain on the environment, according to this opinion piece by Dr Robert Crawford from Melbourne University. There are two charges here – one is that the average 238m2 greenfield house is too big and the other is that the occupants are too reliant on cars for transport. I discussed the transport issues related to greenfield houses recently, so this time I want to look at the allegation of excessive dwelling size.

Huge houses on the urban fringe are an irresponsible drain on the environment, according to this opinion piece by Dr Robert Crawford from Melbourne University. There are two charges here – one is that the average 238m2 greenfield house is too big and the other is that the occupants are too reliant on cars for transport. I discussed the transport issues related to greenfield houses recently, so this time I want to look at the allegation of excessive dwelling size.

There are all sorts of problems with the “too big” criticism, not least the obvious question: what is the “right” size for a dwelling? Even if that question could be answered satisfactorily, there’s another – what should be done about it? Should there be regulations limiting the size of houses? Or perhaps a “McMansions” tax? I think there’s actually a sensible way to approach this issue which I’ll come to in due course. But I want to start with some pertinent observations.

First, greenfield houses mostly aren’t as big as epithets like “McMansion” imply. When Melburnians think “McMansion” they usually have in mind a two storey house like Metricon’s 530 m2 ‘Monarch’, which is more than double the size of the average greenfield house. In the US however, the term McMansion is reserved for much, much bigger houses on very large lots like Tony and Carmela’s spread in New Jersey (see first picture). The average house on Melbourne’s fringe, however, is a much more modest 238 m2 according to Dr Crawford’s own evidence. That’s big compared to an inner city apartment but it’s much smaller than the ‘Monarch’ and much smaller than any reasonable definition of a McMansion. Further, more than two thirds of houses in Melbourne’s greenfield areas are single story. Nearly half (47%) are smaller than 240 m2. Almost three quarters (74%) are smaller than 280 m2.

Second, fringe houses aren’t much bigger, if at all, than typical houses in some older suburban areas. I live with my family 8 km from the city on the border of Ivanhoe and Alphington where most dwellings were built before WW2. Having two children who went to Alphington Primary School means I’ve seen inside many, many homes in the Alphington, Fairfield, Ivanhoe area. I can’t recall ever being in a house in these neighbourhoods that hasn’t been extended at least once in its lifetime. And while they probably were once, these aren’t small houses anymore. For example, the external dimensions of our place, including the garage (but excluding decks), is 240 m2 and it’s by no means large relative to other detached houses in the area – in fact I’d say it’s about average or perhaps even a bit smaller. Yet I don’t hear many complaints that inner suburban homes are “too big”. Read the rest of this entry »

Were those the good old days?

Posted: June 14, 2011 Filed under: Planning | Tags: 1954, Austerica, M I Logan, manufacturing, Planning for Melbourne's Future, Robin Boyd 6 Comments Here’s a fascinating look back to what planners (the MMBW) were thinking about Melbourne’s future nearly 60 years ago. In some ways not much has changed – like many contemporary planning proposals, this is propaganda but in those days they didn’t bother with thin disguise. I like the ending: “will it achieve your support?”.

Here’s a fascinating look back to what planners (the MMBW) were thinking about Melbourne’s future nearly 60 years ago. In some ways not much has changed – like many contemporary planning proposals, this is propaganda but in those days they didn’t bother with thin disguise. I like the ending: “will it achieve your support?”.

It seems that even as long ago as 1954, workers were spending two hours a day commuting and not only were roads congested but so were trams and trains!

The founders of the city could not visualise that one day workers who could walk to their jobs would spend more than one hour each day getting to and from their place of work, that trams would be unable to handle the peak hour crowds, that trains would become hopelessly inadequate for the handling of the enormous flow of commuters into and away from the city, and that with the coming of the motor car the original wide streets would become incapable of handling the ever increasing traffic flows”.

I’m surprised the introduction shows old buildings like Parliament House rather than new ones. After all, this was the new world of modernism and Robin Boyd’s famous attack on Austericanism – the “imitation of the froth on the top of the American soda-fountain drink” – was a mere three years away.

I’m also somewhat surprised that even as late as 1954 the CBD was seen as sucking the life out of inner city retail strips – presumably places like Smith Street – and the inner suburbs were in turn being invaded by industry:

As the city centre has grown in importance, many old shopping centres have declined and the living conditions in many of the surrounding suburbs have deteriorated. Industry had expanded into them and people have moved farther out to live. This has often resulted in an undesirable mixture of shops, houses and factories and the growth of slum conditions Read the rest of this entry »

Where does Melbourne end (and sprawl begin)?

Posted: June 12, 2011 Filed under: Growth Areas | Tags: Bacchus Marsh, Decentralisation, Geelong, journey to work, Macedon Ranges, Moorabool, rural, sprawl, urban, Urban Growth Boundary 11 Comments Drive out towards Warburton and it seems easy to see where Melbourne ends and rural life begins. One minute you’re driving through houses, shops and businesses, when all of a sudden you’ve arrived in country. Except you’re actually still in Melbourne because the official boundary of the metropolitan area lies on the other (eastern) side of Warburton!

Drive out towards Warburton and it seems easy to see where Melbourne ends and rural life begins. One minute you’re driving through houses, shops and businesses, when all of a sudden you’ve arrived in country. Except you’re actually still in Melbourne because the official boundary of the metropolitan area lies on the other (eastern) side of Warburton!

People seem to like a hard edge – a clear and unambiguous boundary – between city and country. But it only works if the non-developed land is “pure” bush or bucolic farming land, without service stations, hobby farms or other urban detritus. Head out of Melbourne in most other directions and development – almost all of it tacky and ugly – tracks you like a mangy dog.

The continuous built-up area of Melbourne (the pink bit in the middle of the map) occupies less than 2,000 km2. This is much less than is commonly assumed by the media and is just a little more than a quarter of the area covered by the official or administrative boundary, which is 7,672 km2. There are a number of “islands” of development within the boundary (also shown in pink), like the townships of Melton and Sunbury, that are officially part of the metropolitan area but separated from “mainland Melbourne” by green wedges. It makes sense to count a place like Melton township as part of Melbourne because 65% of workers living there travel across 9 km of green wedge to work in mainland Melbourne.

These islands make discussions about sprawl particularly fraught. Is it just the central core of continuous urbanised development that sprawls or should all the islands within the boundary also be included? If they are, then that not only includes towns such as Melton, Sunbury and Pakenham, but also towns like Warburton, Healesville and Gembrook that appear to the first-time visitor to be country towns. And given that island townships like Garfield and Bunyip in the outer south-east corridor are officially part of Melbourne, it’s reasonable to wonder why towns that lie just outside the boundary, like Drouin and Warragul, aren’t also seen as part of Melbourne’s sprawl.

This story from a 2003 issue of The Age shows how closely linked many country towns located outside the boundary are to Melbourne:

Census 2001 figures cited by a Monash University Centre for Population and Urban Research report for the Southern Catchments Forum show that, remarkably, more than half of the working residents of the Macedon Ranges area are employed in Melbourne. Similarly, about 40 per cent of the working residents of the Moorabool region (which includes Bacchus Marsh) and the Melbourne side of the Greater Geelong area commute to Melbourne for work. It’s clear, the report says, that these areas are “largely dormitory towns servicing the metropolis. Read the rest of this entry »

Can cyclists and pedestrians coexist?

Posted: June 9, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: 3 way street, bicycle, conflict, Cycling, pedestrians 28 CommentsThis fascinating video by designer Ron Gabriel shows the problems caused by errant motorists, pedestrians and cyclists at an intersection in Manhattan. Each class of traveller has members who act selfishly and inconsiderately toward the others. This is just one of 12,370 intersections in New York City – they are the site of 74% of traffic accidents in the City, according to the video.

Cars are the biggest problem because they can do the most harm to other users, but at least they usually keep off areas dedicated exclusively to walking. A new problem emerging with the increasing popularity of cycling is bikes intruding into areas like footpaths, squares and promenades usually considered the sole domain of pedestrians. I wouldn’t dare make a sudden move when walking along the river at Southbank without checking first to see if there’s a cyclist threading his way through the throng who might possibly collect me!

Mounted cyclists do not mix well with pedestrians on footpaths. Those who cycle in crowds at speed are of course more dangerous, but speed is a relative term. I don’t relish being stabbed by a Shimano 105 shifter carrying the momentum of an 80-90 kg man, even if it’s only moving at 10 kph. My greatest worry was when my kids were very young and likely to run about unpredictably – they should be able to do that in a pedestrian area without the risk of being collected by a bike. In fact I think the greatest risk is from 10 kph cyclists who track too close to walkers, leaving no room for avoiding an incident with pedestrians who don’t behave as predictably as the cyclist (incorrectly) anticipated.

As I understand it, cycling in pedestrian areas is illegal for anyone over the age of twelve unless they’re supervising a child who’s also cycling. It isn’t just an issue of endangering pedestrians – it also makes walking a less enjoyable and relaxed way of getting from A to B. What’s more, like cyclists running red lights, it can potentially reinforce the negative perceptions and rhetoric of the anti-cycling brigade. The cyclist who ignores red lights really only puts himself at risk, but if he cycles in pedestrian areas he can put others at risk. Read the rest of this entry »

How many travellers use the trains?

Posted: June 8, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: boardings, Clifton Hill, Epping, Hurstbridge, patronage, rail, rail stations 22 CommentsThe President of the Public Transport Users Association, Daniel Bowen, posted some “unofficial” stats last week on boardings at Melbourne’s railway stations in 2008-09. I’ve used these numbers to put together the accompanying exhibit showing the number of weekday boardings on the Epping and Hurstbridge lines. These two lines join into one at Clifton Hill so I’ve shown the section from there to Jolimont separately (too much effort to do any other lines!).

Daniel emphasises these numbers come with no warranty as to their accuracy but they did come from a “good source” in the Department of Transport. He reckons inflating the numbers by 11.4% will give a fair estimate of 2010-11 boardings.

I want to make a number of essentially speculative observations prompted by these numbers (for the purposes of this discussion I’ll leave the numbers as they are).

First, there seems to be no statistically significant relationship between the number of boardings and distance from the city centre i.e. from Jolimont to both Epping and Hurstbridge (admittedly my measure of “distance” is rank order of stations not kilometres, but I don’t think that matters). So while the proportion of the population resident around each station that uses the train generally declines with distance from the centre, the absolute number of boardings isn’t correlated with distance.

This may seem surprising because stations close to the centre are more proximate to the CBD’s many and various attractions and might be thought to enjoy higher dwelling densities than more distant stations. However it appears that other variables, such as the accessibility of a station to the surrounding population, are a more important determinant of the number of boardings.

Second, location on a junction of the rail network is not a guarantee of a large volume of boardings and nor does the absence of a junction mean a station will only ever have a minor role. Clifton Hill is the only station on this line that’s on a junction and has a reasonably large number of boardings, but not as many as Ivanhoe, Heidelberg or Reservoir.

Clifton Hill only ranks 36th in patronage of all stations (excluding the five loop stations) but that’s better than two other “junction” stations, Burnley (48th) and North Melbourne (90th). Eight of the 20 largest (non-loop) stations happen to be on junctions but twelve aren’t — my interpretation is being on a junction was a distinct advantage in the early days of rail and gave those eight a head start. Nowadays however the broader characteristics of centres appear to be more important drivers of boardings. For example, Ivanhoe is not a large activity centre in terms of jobs, but its station serves two large private schools and is an important pick-up point for buses serving schools in Kew. Heidelberg also has a school but more importantly has a large number of jobs in and around the Austin Hospital and has the local courthouse. Clifton Hill is disconnected from the nearby retail strip, has little nearby space for commercial or more intensive housing development, and is “in competition” with the No. 86 tram. Read the rest of this entry »

Is parking the best use of CBD streets?

Posted: June 7, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: auto, car, Manhattan, Melbourne City Council, parking, pop-up cafe, transport strategy, WBP Property Group 30 CommentsHere’s an interesting nugget of information from Melbourne City Council’s new Transport Strategy – there are 4,190 parking spaces in Melbourne’s CBD, of which 3,077 are metered. There are however more than 60,000 off-street parking spaces “in the centre of the city”. That means on-street spaces account for just 6% or so of all city centre parking.

This suggests that in the CBD at least, on-street parking is not that important in the overall scheme of things. It’s currently used solely for short-term parking, but commercial parking stations can also perform that function. Indeed, they’d probably prefer the higher income that comes with rapid turnover. Car storage is a remarkably low value use for such premium land. Even in the case of the metered spaces, the price charged is well below the value the land could theoretically fetch in some alternative use.

According to Greville Pabst, chief executive of valuers WBP Property Group, a “car space in a typical city apartment can add from $40,000 to the purchase price and, in some instances, for upmarket apartments in good locations, it can add more than $100,000 to the price tag”. Even in inner city residential areas, the Mayor of the City of Yarra estimates a parking space adds about $50,000 to the value of an inner-city property. In Sydney’s CBD a garage costs as much as $120,000 to $150,000.

There is an opportunity here to do away with all or most on-street parking in the CBD and instead use the space for something more valuable. It could be used for high capacity vehicular modes like buses, trams and motorcycles; for highly valued sustainable modes like cycling, walking or shared car schemes; or for amenity-enhancing uses that could take advantage of ground level proximity to pedestrian traffic.

Parking spaces could be dedicated permanently to new uses – for example a cafe. Given an unrestricted brief, businesses would come up with innovative ways to use these narrow spaces for other purposes. Manhattan’s “pop-up” restaurants provide an interesting take on possible alternative uses.

Of course Council could simply start charging parking fees that reflect the real value of the land, hopefully with a demand-responsive tariff. Prices would presumably be relatively similar to what commercial parking operators charge – somewhat less because they’re not protected from the weather or supervised, but somewhat more for those that are a bit closer to the action. It would need to be examined closely but my view is the social value of alternative uses would still be higher. Read the rest of this entry »

Should motorcycles have a bigger role?

Posted: June 6, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: Hanoi, motorcycles, safety, scooters 10 CommentsPublic transport, cycling and hybrid cars get a lot of attention as responses to climate change and peak oil, but the potential of scooters and small motorcycles seems to pass largely unnoticed. That’s a pity because powered two wheelers are the mode of choice in places like Hanoi where fuel prices are very high relative to incomes. They offer the key advantages of cars – on-demand response, a direct route to the traveller’s destination and speed – but at much lower cost. Indeed, if fuel prices go stratospheric, I expect a very large number of urban Australians will choose this mode of travel ahead of public transport.

A lot of policy attention is quite properly given to improving the safety of riders, but very little is given to developing scooters and motorcycles (hereinafter SAMs) as part of a comprehensive transport strategy. That’s unfortunate because there would potentially be many benefits for the wider society if they had a much larger share of all travel within our capital cities.

SAMs (and I include power-assisted bicycles in this category) have many attractions for riders. They are remarkably inexpensive to purchase and cost little to run. They can be ‘threaded’ through congested traffic, are cheap to park, and in some places they can be parked legally on footpaths. Most machines can carry a passenger and small items like groceries (or much more in Hanoi!). Most importantly, riders don’t have to wait for them, or transfer to another one mid-journey, or stop frequently, or take a circuitous route to get where they’re going. In most places they’re so easy to park that riders don’t have to walk far to them either.

Compared to the large proportion of car journeys that involve only the driver, SAMs also have many social benefits. They require only a fraction of the road space, consume much less fuel and emit considerably less greenhouse gas. They need little space for parking and don’t require new dedicated infrastructure (although some improvements to roads would help). Most importantly, they are potentially attractive to new classes of travellers because, like bicycles, they’re private and hence flexible.

The share of trips taken by SAMs may increase organically in the future in response to higher petrol prices and increasing traffic congestion. But given their social benefits, it would be good policy to actively encourage greater uptake of SAMs in lieu of driving. Safety is the key obstacle, so that’s where any strategy has to start. Current approaches to safety stress factors like rider skills and greater awareness of SAMs on the part of drivers. These are important, however within large urban areas the best strategy is safety in numbers. Achieving a critical mass of riders could be facilitated by initiatives such as lowering registration charges for small capacity SAMs, relaxing restrictions on lane-splitting, giving riders access to transit lanes, and increasing the supply of dedicated parking spaces (with locking points). There might also be scope for small works – for example, access lanes could be reserved to enable riders to move directly to the head of traffic at intersections.

But there are other important issues that need to be addressed too. Engines in SAMs are not generally as sophisticated in dealing with pollutants on a per kilometre basis as car engines. Nor are they generally as quiet under acceleration. These drawbacks are partly technical – it’s harder, for example, to incorporate catalytic converters in SAMs – but they can also be addressed through better regulations and more pro-active enforcement. In the medium term, electrically powered SAMs may mitigate some of these problems. Read the rest of this entry »

Are apartments the answer to ‘McMansions’?

Posted: June 5, 2011 Filed under: Growth Areas, Housing | Tags: apartments, energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, houses, Melbourne University, sprawl 5 CommentsDemonising sprawl seems to be the mission of many planners, academics and journalists, but oftentimes zealotry leads to mistakes, as with this claim that infrastructure costs on the fringe are double those in established suburbs. I’m reminded again how easy it is to get the wrong end of the stick on this issue by a study released last week by the Architecture Faculty at Melbourne University.

The University’s media release tells us the study found “houses on Melbourne’s suburban fringe are responsible for drastically higher levels of greenhouse gas emissions compared to higher density housing or apartments in the inner city”. The Age ran with the media release, reporting that bigger dwellings and more car-based travel are the key reasons fringe houses consume more energy and emit more greenhouse gas than apartments.

I can’t refer you to a full copy of the study because the University didn’t make it available to the media or the public. That didn’t seem to worry The Age, but I think it’s an extraordinary decision – does the University exist to issue media releases or to undertake serious research? I contacted one of the authors who told me the study is a journal article and he couldn’t give it to me for copyright reasons. He gave me this link to the abstract. I’ve read the full article but if you don’t have on-line access you’ll have to spring for €35 if you want to read it.

A key part of the study is a comparison of the (embodied, operating and transport) energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions of households in three building types – a 100 m2 two bedroom high-rise apartment in Docklands 2 km from the city centre; a 64 m2 two bedroom suburban apartment 4 km from the centre in Windsor; and a 238 m2 detached house in an outer suburban greenfield development 37 km from the centre (the latter is shown in the accompanying chart in two versions – a 2008 five star and a “future” seven star energy rated version).

I don’t know what the point of this sort of comparison is. Putting transport aside (you’ll see why later), there’s little policy value in comparing a $1 million plus Docklands apartment with a $500,000 plus suburban apartment in Windsor, much less comparing both with a $350,000 house and land package on the urban fringe (and I’d say Windsor is inner city!). Nor does a seven square two bedroom apartment seem like a practical substitute for the sort of household that buys a 26 square four bedroom house.

A better approach would’ve been to compare the greenfield house against a townhouse of similar value located in the established suburbs, say 20 km or more from the centre (or perhaps against a greenfield townhouse set within a walkable neighbourhood). Alternatively, the authors could have followed the ACF’s lead and compared the resource use of all suburban residents with those of inner city residents – but the catch here is the ACF found that, even though on average they live in smaller dwellings, inner city residents have a higher ecological footprint (see here and here)!

The study should be on firmer ground when it compares transport energy and emissions across the three locations, but it isn’t. The trouble is the study gets it completely wrong on this key variable and, frankly, the travel findings just don’t stand up. There are two key weaknesses. Read the rest of this entry »

Is this a real tram ‘network’?

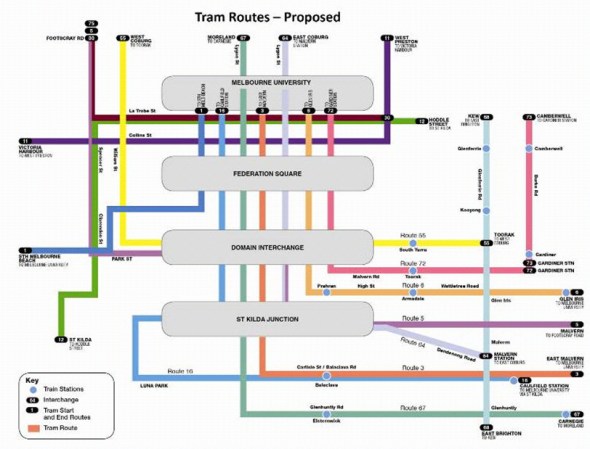

Posted: June 2, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: Clement Michel, light rail, plan, street cars, Swanston St, trams, Yarra Trams 23 CommentsThe Age reported on Yarra Tram’s new plans for Melbourne’s trams during the week. My perpetual beef with The Age is they don’t provide links to background material and in this case they didn’t even provide a diagram. Not good enough in the digital age! So, here’s a presentation by Yarra Tram’s Clement Michel, as well as the accompanying map of the company’s planned new routes.

The presentation highlights the problems with current tram operations that prompted the proposed changes. For example, the No. 96 took 20 minutes to journey from East Brunswick to Spencer St in the morning peak in 1950 but now takes 28 minutes. It spends 50% of the time moving and 17% boarding — but 33% stationary. That compares poorly with tram and light rail systems elsewhere.

The new routes are intended to complement other initiatives, such as greater priority at traffic lights and segregation from traffic. A key purpose is to relieve pressure on Swanston St-St Kilda Rd, which is clogged with a tram every minute and has the friction of 31 traffic lights between Melbourne University and the Domain. Part of the proposal is to route some services via the western end of the CBD. Some Swanston St passengers would have to change trams e.g at Domain Interchange.

It is also proposed to effectively “halve” some long routes and introduce cross town or feeder services (similar to the existing Footscray to Moonee Ponds service) so that loads can be better balanced. Long routes can be inefficient because the number of trams is constant along the route but the loads vary. The changes would mean higher frequencies can be targeted better to busy areas.

An example of the proposed changes is the existing West Preston to St Kilda service. The proposal is to split it into two services — a St Kilda to East Melbourne route operating via Spencer and La Trobe Sts, and a West Preston to Docklands service. Read the rest of this entry »