Are driverless cars a game changer?

Posted: November 30, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: autonomous vehicles, driverless cars, emissions, Public transport 21 CommentsA common observation by many historians I’ve read goes like this: “they failed to understand just how important such-and-such was going to be in the future”. In many cases, “such-and-such” is a decisive technology that went unrecognized until it ended up completely changing the game.

Well, I think one technology that’s being grossly under-estimated today is Driverless Cars (DCs). If they could deliver fully on their promise, they’d have an enormous impact and bring a triple bottom line improvement to our cities – more efficient, more equitable and better for the environment.

There’s plenty of commentary around on driverless cars and I wrote at length on their potential as recently as May 31, in Are driverless cars coming? In that piece, I discussed the current state of the technology and some of the formidable technical, social and legal obstacles to a driverless car fleet.

However as we know from the history of electricity, public sanitation, the car, the computer, inoculation, the pill and many other innovations, it’s very hard to deny an irresistible idea. Given enough time – say the 30 year horizon typical of current planning strategies – it’s possible the sheer weight of benefits DCs promise our cities will provide the motive force to overcome these obstacles.

The key potential benefits are:

- Expansion in the effective capacity of the road system – at least double and perhaps eight times as much, with consequent savings in infrastructure provision

- Time savings from faster journeys – technology can manage vehicle interactions and speeds more efficiently than human drivers (although there might be a trade-off with capacity here)

- Almost complete elimination of serious injuries and fatalities associated with accidents

- More productive use of in-vehicle journey time compared to conventional cars

- Greater mobility for those who cannot drive e.g. the unlicensed, disabled, drunk

These are potentially enormous private and social benefits. In addition, the warrant for owning a private vehicle would be greatly reduced in a world of DCs. If a total or substantial shift to DC-sharing were achieved, the size of the urban car fleet would be reduced by an order of magnitude. There would be many benefits:

- Lower environmental impact because many fewer vehicles would need to be manufactured

- Less public and private space devoted to parking – this could greatly enhance the quality of public spaces and even residential streetscapes

- Better matching of vehicle type to need, resulting in lower resource and environmental costs e.g. many DCs could be single seaters

- Lower cost of travel due to eliminating need for vehicle ownership and removing the “status” component

- Reduced noise, pollution, emissions and energy consumption by virtue of having a more efficient “standard” set of vehicles

- The opportunity to rationalise the way travel is paid for by introducing a new pricing ‘paradigm’ – all standing and variable costs, including externalities, could be incorporated in a distance-related tariff (this isn’t intrinsic to DCs, but the changeover to a new paradigm provides the opportunity)

There are other potential strategic benefits too. Driverless cars could greatly reduce (though not eliminate) the need for public transport. This would offer a number of potential advantages:

- Faster, safer and more private travel for those who currently use public transport – many travellers would enjoy very significant time savings

- A higher proportion of the total cost of providing transport in the city could be borne directly by DC users rather than, as at present, by taxpayers

DCs aren’t just a replacement for the car, they’re a potential game-changer for the entire urban transport task. Read the rest of this entry »

Is The Age providing fair comment on transport issues?

Posted: November 29, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: Department of Transport, East West Tunnel, Eastern Freeway, Eddington Report, Kenneth Davidson, Melbourne Metro, Northern Central City Corridor strategy, Regional Rail Link, Sir Rod Eddington 6 CommentsI take an agnostic view of freeway proposals – I don’t assume apriori that they’re all bad or all good. I prefer to look at the evidence first before deciding if a proposal has merit or is a poor idea. But it seems there are some who will overlook evidence to the contrary if it undermines their ideological view.

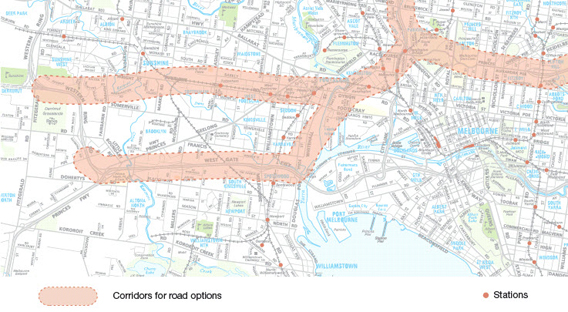

Like Kenneth Davidson in his column in The Age on Monday, Why the east-west road tunnel is a stinker, I have some misgivings about the tunnel proposed to connect Melbourne’s Eastern Freeway with the Western Ring Road. The Victorian Government has just submitted a proposal to Infrastructure Australia, seeking funding to develop the tunnel idea further.

My key concern is the anaemic benefit-cost ratio. But Mr Davidson, who’s a senior columnist at The Age, goes further. He reckons the proposed tunnel recommended in 2008 in the Eddington Report is a “stinker” and a “confidence trick”.

That’s because an earlier study undertaken for the Bracks government in 2004, the Northern Central City Corridor strategy (NCCC), found most of the traffic coming off the Eastern Freeway heads into central Melbourne. It found only 15% is bound for the northern or western suburbs. “In other words”, Mr Davidson says:

the public justification for the east-west link – that it would take traffic away from the central business district – was a confidence trick……The first question (Eddington) should have asked was where did the 2004 study go wrong.

I don’t think anyone disputes the NCCC study was negative about the case for the tunnel. Nor is Mr Davidson the first to raise this objection. The “gotcha” Mr Davidson seizes on with such alacrity is that Sir Rod Eddington apparently ignored the NCCC study’s key finding.

But it seems it’s Mr Davidson who’s doing the ignoring. The Eddington Report actually does consider the NCCC study. Moreover it deals with it in a way that is prominent and impossible to miss by anyone with their eyes open (read it – Chapter 5, page 129).

The Report argues it’s a myth that nearly all Eastern Freeway traffic is destined for the inner city. It says the NCCC produced diagrams that present “a distorted view of traffic distribution (and further NCCC modelling for a future link would have identified and addressed this issue)”.

In a section titled, ‘Myth 2: nearly all the Eastern Freeway traffic is destined for the inner city’, It argues the NCCC study didn’t look beyond the capacity of existing roads or the ultimate destination of traffic once it left the NCCC study area.

First, given the roads in question, the traffic distribution (identified in the NCCC study) is not surprising: at the end of the freeway, there are ten freeway standard traffic lanes (five each way). By the time traffic reaches Macarthur Avenue in Royal Park, the corresponding ‘connection’ is a two-lane road (one lane each way). The traffic distribution is as much a function of the roads available, which progressively reduce in capacity towards the west, as it is a reflection of the demand for a particular direction of travel.

Secondly, when the (Eddington) Study Team analysed how traffic from the Eastern Freeway is distributed (with the analysis closely matching the NCCC distribution), it revealed that around 40 per cent of the daily traffic from the freeway travels beyond the central city area – to the south and the west. That is the case with the current network: in the future, EastLink will add a new dimension.

The Eddington Report also argues (page 137) the NCCC study focussed on Eastern Freeway traffic and didn’t fully consider traffic using adjacent streets instead. Moreover, it didn’t recommend against the tunnel because insufficient vehicles would use it, but rather because the high cost of construction yielded an inadequate benefit-cost ratio. Read the rest of this entry »

Are we set to commute even further?

Posted: November 10, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic, Public transport | Tags: BITRE, commuting, trip distance 7 CommentsThe Age says jobs in Melbourne are losing pace with sprawl – it cites a new study by BITRE which predicts “an increase in the average commuting distance” by 2026 and a rise in journeys to work involving a road distance of more than 30 kilometres.

If a rigorous, hard-nosed body like the Bureau of Transport, Infrastructure and Regional Economics is saying things are going to get worse in the future, it’s worth sitting up and taking notice, right? It’s true BITRE does say that, but it’s also true the media tends to err toward a sensational rather than a sober interpretation of any given facts. In this instance the story is a bit of a beat-up.

For a start, it’s hardly news that commuting distances could “increase” over a period of 15 years given the spectacular growth in population projected for Melbourne. What matters is the size of any increase – if it’s only a 1% increase over the entire period, that’s an infinitesimal 0.06% p.a. However if it’s (say) 15%, i.e. 1% p.a., that’s worth taking note of. However The Age is silent on this score.

BITRE doesn’t say anything about the size of the predicted increase either. There’s a good reason for that. BITRE’s study isn’t an authoritative prediction of future commute distances as implied by The Age’s story. It doesn’t make forecasts based on the latest data, using innovative modelling techniques and complex algorithms as one might expect. In fact the report isn’t even about the future! – it’s actually about historical population, employment and commuting patterns in Melbourne up to 2006.

The Age relies on what is in effect an ill-advised throwaway line by BITRE. The report states (p 333) that if the Victorian Government’s spatial projections of population and employment through to 2026 are realised, the likely commuting implications include….”an increase in journeys to work involving a road distance of more than 30 kilometres and an increase in the average commuting distance”. There’s no analysis or supporting information behind this assertion, so too much shouldn’t be made of it. The prominence given to it by The Age suggests BITRE should’ve thought a bit harder before including it in a report about the past and the present.

However what BITRE actually has analysed in-depth is the historical change in travel distances – and here the picture is if anything somewhat mixed. The report looks first at what’s happened over 2001-06 (see exhibit). That isn’t necessarily a guide to what will happen in 2026, but it shows how current patterns are trending. The picture it reveals isn’t one of rampant increases in commute distances but rather one of relative stability.

BITRE found the average commute in Melbourne increased from 14.7 to 14.8 km, or by just 100 metres over five years. That’s a 0.7% increase, or a miniscule 0.1% p.a. Surprisingly, the average commute increased proportionally less in the outer suburbs than in the inner city – in fact as the exhibit shows, the average commute shortened in absolute terms in the Outer South, Outer East and the Outer West.

This is the real news! It’s important because commute distances have historically increased significantly, while commute times have remained relatively stable. So reliable evidence that commute distances have stabilised, even for five years, is noteworthy. Read the rest of this entry »

Should scooters and motor cycles have a bigger role in cities?

Posted: September 12, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: 2WMV, motor cycles, Paris, scooters, Two Wheel Motorised Vehicles, Velib 16 CommentsI’ve argued before that scooters and motorcycles should play a much bigger part in meeting our future transport needs if the cost of motoring increases dramatically in real terms (here and here). That’s because Two Wheel Motorised Vehicles (2WMVs) are cheap to buy, they’re economical to run and they offer many of the advantages of a car, including on-demand convenience and speed. Moreover they’re easy to park and can be threaded through traffic.

We know 2WMVs are very popular in countries like Vietnam where vehicle purchase and running costs are very high relative to incomes, yet they don’t have a high profile in discussions within Australia about how to deal with peak oil and climate change. Because of their low fuel use, small 2WMVs with efficient, clean engines should garner greater attention as a more sustainable transport option.

A new study published earlier this year, The unpredicted rise of motor cycles: a cost-benefit analysis, might help to give more prominence to the two wheel powered option. It shows use of 2WMVs grew strongly in Paris from the start of the new century, when real oil prices began to rise.

Pierre Kopp from the Pantheon-Sorbonne University (Paris-1) found the number of passenger kilometres travelled by 2WMVs increased 36% in Paris between 2000 and 2007*. This was much higher than other modes – rail grew 12% and bus and car fell 21% and 24% respectively. By 2007, 2WMVs accounted for 16% of all road passenger kms in Paris (up from circa 10% in 2000), more than double the share of buses.

The growth in 2WMV use was primarily at the expense of public transport. Of the 380 million additional passenger kms attributable to 2WMVs, a fifth were generated by existing riders travelling more and 27% by travellers transferring from cars. However more than half (53%) came at the expense of public transport.

This is not surprising given the evidence the author presents for the point-to-point time savings offered by 2WMVs over all other modes. Within Paris, they are 46% faster than cars and 50% faster than the Metro. Within the suburbs of the metropolis, they are 39% faster than cars and 34% faster than the RER.

The author calculates the switch from cars to 2WMVs generated an annual travel time saving worth €93 million. He subtracts higher accident, pollution and other costs, giving a net benefit of €102 million. The net benefit from those who switched to 2WMVs from public transport is €62 million. In contrast, the share of the additional 2WMV travel generated by existing riders has a net cost of €3.7 million (mostly reflecting the absence of the sort of dramatic time savings obtained by those who switched from relatively slow cars, trains and buses).

Parisians who switch to 2WMVs are motivated primarily by time savings rather than fuel costs. On the other hand, the main deterrent is safety (interestingly, the big cost component by far is minor accidents rather than serious ones or fatalities). The importance of safety is illustrated by the fact that all the value of the extra trips taken by existing riders was cancelled out by higher accident costs.

The total €160 million net benefit from increased 2WMV travel over the period was achieved with little official support, according to the author. For example, parking for 2WMVs is limited and the number of parking fines doubled over the last seven years. The author contrasts the relatively high level of expenditure on infrastructure aimed at making cycling safer with the paucity of expenditure on 2WMVs, even though, he says, cycling accounts for a mere 0.8% of all road travel (and 6 deaths p.a.) in Paris whereas 2WMVs account for 16% (and 21 deaths p.a.).

I think it’s unfortunate that bicycles and 2WMVs are cast in competing roles for funding, but it’s nevertheless puzzling why small capacity 2WMVs (I exclude big motor bikes) have such a low profile in public policy as a relatively sustainable transport option. This seems as true in Australia as it apparently is in Paris.

It’s puzzling because 2WMVs have many advantages. Compared to bicycles they can travel longer distances, are harder to steal, are more accessible to those who are infirm, can carry a passenger and goods, and riders don’t need to take a shower. Compared to public transport they’re faster point-to-point, they’re private, most of the financial cost is borne by the owner, and they offer on-demand availability. And compared to cars they use less fuel and can handle congested conditions better. Read the rest of this entry »

Do public transport and road pricing go together?

Posted: September 6, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: congestion, pricing, PTUA, Public Transport Users Association, road, The Greens 20 CommentsIt surprises me who’s still lukewarm about congestion pricing of roads. I’d have thought the focus on the carbon tax over the last year would’ve heightened understanding of the role of the price mechanism in managing resources better. Obviously governments find it too hard politically but even organisations like The Greens and the Public Transport Users Association (PTUA) offer only heavily qualified support for congestion pricing.

The PTUA doesn’t support congestion pricing in the absence of alternatives, arguing that it would be unlikely to win community support and would be socially inequitable. It’s position is public transport must first be improved to a competitive level. The Greens take a similar view. Senator Scott Ludlum says the party believes a congestion tax “would be an unfair impost unless significant improvements to public transport and other non-driving modes of commuting, such as walking and cycling facilities, are made at the same time”.

What this means in practice is neither organisation has much to say in favour of congestion pricing – neither could be regarded as a staunch advocate of this potential reform. I think that’s a real pity because congestion pricing and improvements in public transport go hand-in-hand. They are the veritable horse and carriage – you won’t get one without the other.

Cars are a very attractive transport option, especially in our dispersed cities. But even the streets of a dense city like Manhattan are full of cars. We could wait generations in the hope that land use changes will make Melbourne so dense that cars will necessarily become a minority mode. Or we could ignore the probability that motorists will shift to more fuel-efficient vehicles or to ones powered by alternative fuels and instead bet that higher fuel prices will drive cars off Melbourne’s roads.

But waiting and hoping aren’t a good basis for policy. Realistically, we can’t expect Australians will forego the private benefits of a car unless they’re forced to. The only reason most CBD workers don’t drive is because they can’t – traffic congestion and high parking charges rule driving out. Even so, around a quarter of CBD workers in Melbourne still drive and that proportion rises pretty rapidly to 50% and higher once you move even a few hundred metres away from the city rail loop. It would be a bit hard to argue they make this choice because public transport isn’t good enough.

Investing in public transport without simultaneously constraining the car will only achieve a modest increase in public transport’s existing 15% share of all motorised travel in Melbourne. Consider that Melbourne’s train, tram and bus system would cost an unthinkable amount if we had to build it from scratch today – hundreds of billions of dollars – yet 85% of motorised trips are still made by car. It should be obvious that simply providing the infrastructure isn’t enough.

Congestion pricing is the only way to reduce the considerable competitive advantage cars have over public transport (in most situations) within a reasonable time frame and at a reasonable cost. It’s therefore the only way to significantly increase public transport’s share of motorised trips. Of course good public transport has to be in place at the time congestion pricing is introduced. But what The Greens and the PTUA are missing is that you have to positively and enthusiastically embrace both.

The efficiency case for pricing is very strong and rejected by few. It’s the only practical way to manage traffic congestion. Its great virtue is that it prioritises travellers according to the value of their trip purpose. It also reduces accidents, as well as transport-related emissions and pollution.

The key concern of those with misgivings is the equity implications of congestion pricing. I don’t think it can be doubted that richer people will be better placed to buy road space. But I think there are a number of other issues that also need to be considered here. Read the rest of this entry »

Should replacing level crossings be given higher priority?

Posted: August 16, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic, Public transport | Tags: Brian Negus, bridge, Committee for Melbourne, development rights, grade separation, level crossing, overpass, PTUA, RACV, rail, surplus railway land 14 CommentsThe Committee for Melbourne has called for a $17.2 billion program to remove all Melbourne’s level crossings over the next 20 years.

The Committee says just two separations of road and rail were constructed by the Kennett government and two by the Bracks/Brumby government. While Melbourne has 172 level crossings, Sydney tackled the issue years ago and now has only eight.

However the Baillieu government has given an undertaking to grade-separate ten crossings at an estimated cost, on average, of around $100 million each. The Committee reckons the private sector could pay a big chunk of the $17.2 billion cost in return for the commercial rights to each site, although the Herald-Sun warns such a move would very likely “be fiercely opposed by anti-development groups”.

There’s a lot to be said for giving a higher priority in the transport capital works program to eliminating level crossings, as they present a number of problems. One is they slow traffic, including buses and trucks. According to the RACV’s public policy manager, Brian Negus, crossings along the Dandenong line are closed for 30-40 minutes an hour during the peak, exacerbating traffic congestion. This is likely to become a bigger problem as the share of public transport trips carried by buses increases. The interaction between crossings and nearby signalled junctions is a major barrier to the efficient performance of the transport network.

Level crossings also impose a limit on the frequency of train services. There are only so many trains that can realistically be sent down a line given each service entails stopping traffic in both directions for well in excess of one minute (in Newcastle, crossings are closed on average for passenger and freight trains for between three and seven minutes!). Some crossings are forecast to carry nearly 40 trains per hour in the peak by 2021. Another issue is traffic queuing across rail lines — as well as the occasional car/train incident — limits the efficiency of the network. Further, level crossings are a safety hazard for pedestrians and give parents a reason to discourage children from walking to school.

While I’ve not seen an analysis for Melbourne, there’s little doubt the benefit-cost ratio of level crossing elimination would be very high. I expect it would be well ahead of some other much larger transport projects, such as the Avalon, Doncaster or Rowville rail proposals.

There are nevertheless a number of issues raised by this proposal. One is the need to prioritise works – some crossings are relatively minor and simply don’t warrant expenditure in the forseeable future. Probably 80% of the benefits will come from grade separating 20% of crossings. Back in 2009, the Public Transport Users Association argued these ten crossing should be given the highest priority, given their impact on road-based public transport:

- Bell Street and Munro Street, Coburg (one project) (Smartbus 903)

- Springvale Road, Springvale (Smartbus 888/889)

- Bell Street, Cramer Street and Murray Road, Preston (one project) (Smartbus 903)

- Glen Huntly Road and Neerim Road, Glenhuntly (one project) (Tram 67, and trains subject to speed restrictions)

- Balcombe Road, Mentone (Smartbus 903)

- Buckley Street, Essendon (Smartbus 903)

- Clayton Road, Clayton (Smartbus 703)

- Burke Road, Gardiner (Tram 72, and trains subject to speed restrictions)

- Camp Road, Campbellfield (crossing elimination and new station) (proposed Smartbus 902)

- Glenferrie Road, Kooyong (Tram 16, and trains subject to speed restrictions)

That’s a particular perspective, yet it matches some of the RACV’s priorities. Last year the RACV said the four worst crossings in Melbourne are in High Street near Reservoir station, on Burke Road near Gardiner station in Glen Iris, on Clayton Road next to Clayton station, and Murrumbeena Road near the station. The Dandenong rail corridor also figures high in the RACV’s priorities.

I’m not sure there is as much value in development rights as the Committee for Melbourne imagines. Many level crossings, perhaps most, may not have enough suitable land available for development after meeting grade separation and operational needs. The most promising opportunities are probably where the rail line rather than the road has been lowered, but this can be expensive. Many of those that do have land available may be in locations considered unsuitable for development by planners. And let’s be clear that development in air space over railway lines is a fantasy – it’s simply too expensive in all but an extremely small number of cases. For practical purposes, development in air space is not an option. Read the rest of this entry »

Are Toyota Prius drivers wankers?

Posted: July 20, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: Alison Sexton, conspicuous conservation, conspicuous consumption, Honda Civic, hybrid, Larry David, mcmansion, signalling, Steven Sexton, Toyota Prius 26 CommentsEducated elites often show distaste for the sort of conspicuous consumption exemplified by McMansions, but it seems almost everyone likes to show off, even greenies.

Two US researchers, Steven Sexton and Alison Sexton (they’re twins), have coined the term “conspicuous conservation” to describe people who spend up big to signal their green status. The standard conventions of conspicuous consumption still apply – like German cars and appliances – but now esteem can also be bought through demonstrations of austerity.

The authors set out the issue in this paper, Conspicuous Conservation: The Prius Effect and Willingness to Pay for Environmental Bona Fides:

Amid heightened concern about environmental damage and global climate change, costly private contributions to environmental protection increasingly confer status once afforded only through ostentatious displays of wastefulness. Consumers may, therefore, undertake costly actions in order to signal their type as environmentally friendly or “green.” The status conferred upon demonstration of environmental friendliness is sufficiently prized that homeowners are known to install solar panels on the shaded sides of houses so that their costly investments are visible from the street.

They examine the sorts of people who buy hybrid cars in Washington (State) and Colorado, focussing on areas with a green demographic where sales of hybrid cars are high and where ‘signalling’ green credentials therefore ought to work. They attempt to isolate the “green halo” effect by comparing sales of the market-leading Toyota Prius – which has a distinctive and unique body shape – against those of comparable hybrids like the Honda Civic. Like all of the other 23 hybrid models on the US market (excepting the Prius), the Civic is virtually indistinguishable from the bigger-selling petrol powered variants of the same car. It is only identified by a small badge and hence, unlike the Prius, fails to signal its environmental credentials.

Anyone who’s watched Larry David tootling around LA in his Prius with uncurbed enthusiasm will get the picture – “we’re Prius drivers….we’re a special breed”. As Dan Becker, the head of the global warming program at the Sierra Club says, “the Prius allowed you to make a green statement with a car for the first time ever”.

The authors cite a market research company’s finding that 57% of Prius buyers say their main reason for choosing the Prius is because “it makes a statement about me”. They refer to another study where most of the individuals interviewed had only a basic understanding of environmental issues or the ecological benefits of hybrid cars but purchased “a symbol they could incorporate into a narrative of who they are or who they wish to be”.

The authors conclude that the conspicuous conservation effect accounts on average for 33% of the Prius’s market share in Colorado and 10% in Washington. No wonder it’s come to be known as the Toyota Pious. Read the rest of this entry »

Is it healthy to assume correlation means causation?

Posted: July 11, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic, Education, justice, health | Tags: Environment and Planning References Committee, health, Justin Wolfers, Legislative Council, obesity, physical environment, The Economist, VMT 4 Comments

Association of obesity trend in the US with vehicles miles travelled (left) and with Justin Wolfer's age (right)

The link between the physical environment and health outcomes like obesity is fraught. The Victorian Legislative Council’s Environment and Planning References Committee should bear this in mind as it goes about its new inquiry into the contribution of environmental design to public health.

The Committee might want to start with the first chart in the accompanying exhibit, which comes from a recent issue of The Economist and purports to show that obesity has increased in the US in line with the increase in miles driven over the last 15 years. The chart is based on work done by researchers at the University of Illinois who found “a striking correlation between these two variables – but with a large time lag……This near-perfect correlation (99.6%) permits predictions about obesity rates”.

Expatriate Australian economist and Wharton business school Assoc Professor, Justin Wolfers, points out the folly of this claim. It is, in his words, a “nonsensical correlation”:

When you see a variable that follows a simple trend, almost any other trending variable will fit it: miles driven, my age, the Canadian population, total deaths, food prices, cumulative rainfall, whatever.

To demonstrate his point, Professor Wolfers prepared the second chart showing an even better correlation between changes in obesity over the period and changes in his age – he didn’t even need to resort to a time lag to get such a good fit! He acknowledges The Economist offered the customary caveat that correlation does not equal causation but this chart, he says, is so completely unconvincing as to warrant a different warning: “Not persuasive enough that you should bother reading this article” (in the interests of balance, here’s The Economist’s subsequent response to Professor Wolfer’s charge).

This exchange highlights a problem with much of the research that purports to show the physical environment — particularly density and/or public transport access — has a strong effect on health-related variables like obesity. There’s plenty of evidence of correlation but not much evidence of causation. There’s no doubt obesity is inversely related to both density and access to public transport, but if it turns out these aren’t the underlying drivers of obesity then the economic cost of misdirected policies could potentially be significant.

There are special reasons why it’s hard to establish causation when dealing with real life infrastructure projects and transport/land use programs. These British epidemiologists reviewed 77 international studies examining the effectiveness of policy interventions to reduce car use. They concluded the evidence base is weak, finding only 12 were methodologically strong – and they mainly involved relatively small-scale initiatives like providing better information about travel options or direct financial incentives to reduce driving (incidentally, only half of those 12 actually worked i.e. reduced car use). Read the rest of this entry »

Is exempting petrol from the carbon tax such a big problem?

Posted: July 4, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic, Energy & GHG | Tags: carbon price, carbon tax, CSIRO, emissions, exemption, greenhouse gas, Productivity Commission 9 Comments

Is transport the main game? Source: Productivity Commission: Carbon emission policies in key economies

Given Australia already has a large excise tax on petrol, exempting automotive fuel bought by “families, tradies and small businesses” from the Gillard Government’s carbon tax is not the disaster some would have us believe.

Australia has a minority government so compromise was inevitable – two of the independents, Tony Windsor and Rob Oakeshott, wouldn’t be party to any increase in the price of fuel for their country constituents. It was either put a price on most but not all sources of greenhouse gas, or have the whole idea shot down yet again.

The exemption is expected to apply to petrol, diesel and LPG. Were the tax to apply to petrol, the impact would be modest – a $25/tonne tax is generally estimated to increase the price at the pump by around $0.06 per litre. The CSIRO calculates that even a $40/tonne tax would only raise the price of petrol by about ten cents per litre.

These amounts are much less than motorists already pay via the $0.38 per litre excise tax on petrol and diesel (there’s no excise on LPG). While it might have a “sin tax” dimension in relation to cigarettes and alcohol, in the case of automotive fuel the excise is not aimed at making motorists pay for roads or for the external costs of petrol – it’s just a convenient way of raising revenue (although it’s not as good as it used to be since John Howard abolished automatic indexation of the price in 2001).

Nevertheless the excise tax is a serious deterrent to driving. The Productivity Commission’s recent report, Carbon emission policies in key economies, calculates that “in 2009-10, fuel taxes reduced emissions from road transport by 8 to 23 percent in Australia at an average cost of $57-$59 per tonne of CO2-e”. Although not put in place with the purpose of abating emissions, the excise already has a much more significant effect on driving than any level of carbon price that’s been seriously touted in the political debate. Based on the CSIRO’s estimates, it could be argued its effect is equivalent to a carbon tax of over $100 per tonne (the relationship isn’t linear – there’re diminishing returns from a marginal increase as the fuel tax gets bigger).

Thus there’s a good argument that automotive fuel is one of the few areas where consumers already pay a high level of tax over and above the GST. Indeed, if it were so minded, the Government could’ve imposed the new carbon tax on petrol and diesel and simply provided an equal offsetting reduction in the level of the existing fuel excise tax. There wouldn’t be a lot of political or economic sense in that, but it illustrates the principle. Read the rest of this entry »

Are these curves moving for the same reasons?

Posted: July 3, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic, Public transport | Tags: auto, BITRE, Burea of Infrastructure Transport and Regional Economics, car, Melbourne, per capita passenger travel, Public transport 6 CommentsBack in May I compared the historic level of passenger travel by car in Australia since 1970 against rail and bus, showing the significant flattening in car use from circa 2004-05 and the upturn in travel by public transport. This sort of long term perspective is useful for understanding the relative importance of the changes in each mode — something which isn’t as evident if only the last five or six years is examined.

The accompanying exhibit shows the change in passenger travel by mode just within Melbourne, using data from the Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE). Importantly, it also allows for the increase in population and hence shows the change in per capita passenger travel. The period is the 33 years between 1976/77 and 2008/09.

It can be seen that private – or individual – travel (i.e. car, van, motor cycle) has fallen sharply since 2004/05, by 1,236 km. Conversely, public – or shared – transport travel (i.e. train, tram, bus) increased by 301 km. While the curves are still a long way apart, it’s notable that the gap is closing primarily because Melburnians are driving less.

I haven’t seen anything which shows confidently and unambiguously where the fall-off in driving is happening. For example, is it outer or inner urban driving? Is it certain trip purposes only? Is it fewer trips? Is it shorter trips? Is it confined to particular demographics? Or is it something else entirely? As with most things, the outcome we see most likely results from the interplay of a number of factors, rather than from a single dominant force.

The usual suspects called on to explain these trends include increases in the price of petrol, in traffic congestion, in parking costs, and in the level and quality of public transport. Other explanations include the theory that baby boomers are getting older (and hence driving less) and the conjecture that the long distance drive is increasingly being replaced by cheap air fares (although this relates more to non-urban travel).

Then there’s Gen Y’s declining interest in driving, the impact of new communication technologies and growing interest in health & fitness and environmental issues. There’s also the theory we’ve hit saturation level with driving – we can drive to enough opportunities already, we don’t need more. Perhaps another reason is the increase in women’s workforce participation leaves them with less time and need for driving. Read the rest of this entry »

Are SUVs killers?

Posted: June 28, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: arms race, Maximilian Auffhammer, Michael Anderson, NBER, Pounds that kill, safety, SUV, traffic accident, traffic fatalities, vehicle weight 7 CommentsMy hate-hate attitude towards SUVs hasn’t improved after reading a new US research paper, The pounds that kill, by two University of California (Berkeley) researchers. They show being in a vehicle struck by a 1,000 pound heavier one results in a 47% increase in the probability of a fatality in the smaller vehicle (the paper might be gated for some – here’s an ungated version that looks very similar).

The authors note that from 1975 to 1980, the average weight of US cars dropped from 4,060 pounds to 3,228 pounds in response to higher petrol prices. However average vehicle weight began to rise as petrol prices fell in the late 1980s and by 2005 it was back to the 1975 level. In 2008 the average car was about 530 pounds heavier than it was in 1988.

A key reason for increasing weight is the safety “arms race”. Drivers seek large vehicles because they’re thought to be much safer for occupants than smaller ones, however they are more hazardous for other travellers in smaller vehicles. As the average size of the fleet rises, there’s an incentive for all drivers concerned about safety to trade-up. The authors note the “safety benefits of vehicle weight are therefore internal, while the safety costs of vehicle weight are external”.

Safety is a key public policy issue because road accidents are as dangerous to life as lung cancer. Moreover, traffic accidents kill more Americans aged under 40 years of age than any other cause. While only as quarter as many people die on roads each year as die from lung cancer, the average age of a road accident victim is 39 years compared to 71 years for lung cancer. The aggregate years of life lost from both causes is similar.

Noting that no detailed attempt has been made to measure the external costs of vehicle weight, the authors sought to:

quantify the external costs of vehicle weight using a large micro data set on police-reported crashes for a set of 8 heterogeneous states…..The data set includes both fatal and nonfatal accidents…..The rich set of vehicle, person, and accident observables in the data set allow us to minimize concerns about omitted variables bias.

They estimate a 1,000 pound increase in striking vehicle weight raises the probability of a fatality in the struck vehicle by 47%. Moreover, they find that light trucks like SUVs, pickups and minivans “raise the probability of a fatality in the struck car – in addition to the effect of their already higher vehicle weight”. The authors suggest this additional effect could be due to the stiffer chassis and higher ride height of light trucks, or possibly to the behaviour of light truck drivers. Read the rest of this entry »

Does business oppose congestion charging?

Posted: June 21, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: Acil Tasman, BITRE, congestion charging, road pricing, VCEC, VECCI 15 CommentsI’m very disappointed with the line one of the State’s largest employer associations, VECCI, is taking on road congestion charging. This issue was raised in a report prepared by consultants Acil Tasman for the Competition Commission’s (VCEC) inquiry into a State-based reform agenda.

Congestion imposes such a high cost on business – whether freight or personal business travel – that I’d expect the great majority of VECCI’s members would be better off with pricing. The Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics puts the current cost of congestion in Melbourne at around $3 billion per year, rising to $6.1 billion by 2020 with unchanged policies.

VECCI says it is opposes the idea of congestion charging for three reasons. First, motorists already pay both the CBD Congestion Levy and the fuel excise. Second, there’s no spare capacity in the public transport system to take displaced motorists. Third, the economy can’t handle another tax on top of the forthcoming mining tax and the carbon price.

In regard to VECCI’s first objection, the obvious point is that these existing imposts on motorists aren’t working – many Melbourne roads are still congested at peak times. Despite the lofty title, the CBD Congestion Levy is actually a tax on parking. It’s only had a very minor impact on traffic because most drivers don’t pay it personally – their employers do. It isn’t in any event peak-loaded and of course it does nothing to manage the level of through traffic. And as per the name, the levy only applies to the CBD. The $0.38 fuel excise tax (no longer indexed) does reduce the overall level of travel by motorists, but has no appreciable effect on congestion because it doesn’t vary with the level of traffic or time of day.

So far as the “no spare capacity on public transport” objection is concerned, a congestion price only has to remove a relatively small number of vehicles in order to get traffic moving at an acceptable speed. The vast majority of motorists won’t come seeking a seat on the train – they will continue to drive but, rather than pay with time as they do at present under congested conditions, they’ll pay in cash. Their numbers may increase over time, but so will public transport capacity. Also, revenue from congestion charging should be applied to improving public transport and increasing capacity.

VECCI’s argument that the economy can’t handle another tax is about as nakedly political as you can get. Australia is one of the world’s most vibrant economies and has been growing for 20 years. Motorists, both business and private, can afford to pay their way. In any event, a congestion charge isn’t a tax — as the name says, it’s actually a charge. Motorists pay directly for the quantity of road space they use and get a direct and immediate benefit – faster travel. That means motorists who travel more pay more. It also benefits drivers from all income strata by enabling them to reduce delays when they make high value trips. Read the rest of this entry »

Is parking the best use of CBD streets?

Posted: June 7, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: auto, car, Manhattan, Melbourne City Council, parking, pop-up cafe, transport strategy, WBP Property Group 30 CommentsHere’s an interesting nugget of information from Melbourne City Council’s new Transport Strategy – there are 4,190 parking spaces in Melbourne’s CBD, of which 3,077 are metered. There are however more than 60,000 off-street parking spaces “in the centre of the city”. That means on-street spaces account for just 6% or so of all city centre parking.

This suggests that in the CBD at least, on-street parking is not that important in the overall scheme of things. It’s currently used solely for short-term parking, but commercial parking stations can also perform that function. Indeed, they’d probably prefer the higher income that comes with rapid turnover. Car storage is a remarkably low value use for such premium land. Even in the case of the metered spaces, the price charged is well below the value the land could theoretically fetch in some alternative use.

According to Greville Pabst, chief executive of valuers WBP Property Group, a “car space in a typical city apartment can add from $40,000 to the purchase price and, in some instances, for upmarket apartments in good locations, it can add more than $100,000 to the price tag”. Even in inner city residential areas, the Mayor of the City of Yarra estimates a parking space adds about $50,000 to the value of an inner-city property. In Sydney’s CBD a garage costs as much as $120,000 to $150,000.

There is an opportunity here to do away with all or most on-street parking in the CBD and instead use the space for something more valuable. It could be used for high capacity vehicular modes like buses, trams and motorcycles; for highly valued sustainable modes like cycling, walking or shared car schemes; or for amenity-enhancing uses that could take advantage of ground level proximity to pedestrian traffic.

Parking spaces could be dedicated permanently to new uses – for example a cafe. Given an unrestricted brief, businesses would come up with innovative ways to use these narrow spaces for other purposes. Manhattan’s “pop-up” restaurants provide an interesting take on possible alternative uses.

Of course Council could simply start charging parking fees that reflect the real value of the land, hopefully with a demand-responsive tariff. Prices would presumably be relatively similar to what commercial parking operators charge – somewhat less because they’re not protected from the weather or supervised, but somewhat more for those that are a bit closer to the action. It would need to be examined closely but my view is the social value of alternative uses would still be higher. Read the rest of this entry »

Should motorcycles have a bigger role?

Posted: June 6, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: Hanoi, motorcycles, safety, scooters 10 CommentsPublic transport, cycling and hybrid cars get a lot of attention as responses to climate change and peak oil, but the potential of scooters and small motorcycles seems to pass largely unnoticed. That’s a pity because powered two wheelers are the mode of choice in places like Hanoi where fuel prices are very high relative to incomes. They offer the key advantages of cars – on-demand response, a direct route to the traveller’s destination and speed – but at much lower cost. Indeed, if fuel prices go stratospheric, I expect a very large number of urban Australians will choose this mode of travel ahead of public transport.

A lot of policy attention is quite properly given to improving the safety of riders, but very little is given to developing scooters and motorcycles (hereinafter SAMs) as part of a comprehensive transport strategy. That’s unfortunate because there would potentially be many benefits for the wider society if they had a much larger share of all travel within our capital cities.

SAMs (and I include power-assisted bicycles in this category) have many attractions for riders. They are remarkably inexpensive to purchase and cost little to run. They can be ‘threaded’ through congested traffic, are cheap to park, and in some places they can be parked legally on footpaths. Most machines can carry a passenger and small items like groceries (or much more in Hanoi!). Most importantly, riders don’t have to wait for them, or transfer to another one mid-journey, or stop frequently, or take a circuitous route to get where they’re going. In most places they’re so easy to park that riders don’t have to walk far to them either.

Compared to the large proportion of car journeys that involve only the driver, SAMs also have many social benefits. They require only a fraction of the road space, consume much less fuel and emit considerably less greenhouse gas. They need little space for parking and don’t require new dedicated infrastructure (although some improvements to roads would help). Most importantly, they are potentially attractive to new classes of travellers because, like bicycles, they’re private and hence flexible.

The share of trips taken by SAMs may increase organically in the future in response to higher petrol prices and increasing traffic congestion. But given their social benefits, it would be good policy to actively encourage greater uptake of SAMs in lieu of driving. Safety is the key obstacle, so that’s where any strategy has to start. Current approaches to safety stress factors like rider skills and greater awareness of SAMs on the part of drivers. These are important, however within large urban areas the best strategy is safety in numbers. Achieving a critical mass of riders could be facilitated by initiatives such as lowering registration charges for small capacity SAMs, relaxing restrictions on lane-splitting, giving riders access to transit lanes, and increasing the supply of dedicated parking spaces (with locking points). There might also be scope for small works – for example, access lanes could be reserved to enable riders to move directly to the head of traffic at intersections.

But there are other important issues that need to be addressed too. Engines in SAMs are not generally as sophisticated in dealing with pollutants on a per kilometre basis as car engines. Nor are they generally as quiet under acceleration. These drawbacks are partly technical – it’s harder, for example, to incorporate catalytic converters in SAMs – but they can also be addressed through better regulations and more pro-active enforcement. In the medium term, electrically powered SAMs may mitigate some of these problems. Read the rest of this entry »

What can we do with Hoddle St?

Posted: June 1, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic, Public transport | Tags: DART, Doncaster rail line, Elliot Perlman, Hoddle St, Punt Rd, traffic congestion 14 CommentsIn Elliot Perlman’s Melbourne-based novel, Three dollars, Eddie thinks the only advice he could offer his daughter is the solution of differential equations and an insight into which trains go via the city loop and why. He imagines that on his deathbed and with his last breath he would say: “Abby, my darling daughter, remember this: no matter where you are or what time of day it is – avoid Punt Road”.

Eddie’s fatherly advice is borne out by the numbers in VicRoad’s Hoddle Street Study: existing conditions summary report. It shows that 10,000 vehicles per hour travel on Hoddle Street in the middle of the day, only a little more than the 9,700 per hour that use it in the morning peak. And as the accompanying graphic of traffic volumes across the Punt Rd bridge shows, traffic on Saturday and Sunday is higher than on Monday, Tuesday and Thursday.

So if you think the Hoddle St corridor is always busy you’re right. The two-way traffic volume on Hoddle St in the section between the Eastern Freeway and Victoria Pde is 85,000-90,000 vehicles per day. There are also a further 27,000 bus passengers on a weekday, so the number of people travelling along Hoddle St is large. This is a conservative estimate – it doesn’t count passengers in cars.

What to do about Hoddle St is a difficult question and I’d like to hear some suggestions. The Baillieu Government is reported (here and here) to have shelved work on VicRoad’s study of options for the corridor. The remaining money has instead been transferred to the study of the proposed Doncaster rail line. This makes sense politically if the Government feels it is obliged to deliver on the railway line. It could argue that the train will reduce traffic congestion, and thereby make the significant cost of upgrading Hoddle St unnecessary.

While it might fly politically, it’s hard to see that a Doncaster rail line would make much difference to conditions on Hoddle St. The space vacated by any drivers transferring to rail would in due course be filled by others, so it would have no lasting impact on traffic congestion. Not that it’s likely many car commuters would even elect to use the Doncaster train instead of Hoddle St.

As I pointed out here, analysis of journey to work data from the 2006 Census undertaken for the Eddington Report shows the number of workers living in the municipality of Manningham who commuted to the City of Melbourne at the 2006 Census was small – just 8,500 (i.e. 17,000 two-way trips). And the number is declining – this was 700 fewer than in 2001. Nor is this group likely to get much bigger due to growth, as the population of the municipality of Manningham is projected to increase by a paltry 0.7% p.a. out to 2031.

Of these 8,500 commuters, 5,100 drove to work and 3,150 already took public transport. The latter group mostly used buses but a third used the Hurstbridge and Belgrave-Lilydale rail lines in neighbouring municipalities (this was before the new Doncaster Area Rapid Transit services started late last year). If a new Doncaster rail line were to achieve the same mode share as in nearby municipalities like Whitehorse, Banyule and Maroondah that already have rail, around 1,600 Manningham commuters could be expected to stop driving to work and change to public transport. That does not seem a very large number in the context of the likely cost of a Doncaster rail line. Even assuming those 1,600 all currently use Hoddle St to get to the City of Melbourne, that’s only a reduction of 3,200 trips. Read the rest of this entry »

Are driverless cars coming?

Posted: May 31, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: driverless cars, driverless trains, Google, Public transport, Tyler Cowen 4 Comments

This alarm clock would be a real incentive to get out of bed (albeit shredding notes is illegal). From Mashable - h/t Alex Tabarrok

There are nine completely driverless train systems/lines operating in Europe, eight in Asia and six elsewhere. There are a further nineteen in Europe with a “standby driver” or, like London’s Docklands Light Railway, with a “Passenger Service Agent” present on the train, just in case something goes wrong.

So Google’s claim that its seven driverless test cars have driven 1,000 miles on roads without human intervention and more than 140,000 miles with only occasional human control sounds plausible. The company is reported by the New York Times as saying one car drove itself down Lombard Street, one of the steepest and curviest streets in San Francisco.

According to the paper, Google’s engineers say “robot drivers” are better because they:

React faster than humans, have 360-degree perception and do not get distracted, sleepy or intoxicated……They speak in terms of lives saved and injuries avoided — more than 37,000 people died in car accidents in the United States in 2008. The engineers say the technology could double the capacity of roads by allowing cars to drive more safely while closer together.

Although they are some years away yet, the claimed potential benefits of this new technology are enormous. If proven, it should allow travellers to do other things while driving, making time spent travelling much more productive. On roads where conventional vehicles have been superseded, road capacity should at least double, although according to some observers an eight-fold increase can easily be achieved. Speeds should increase while simultaneously reducing road accidents — one of the largest negative externalities associated with roads — through keeping drunk drivers away from the wheel and minimising simple driver error. If accidents are less likely, vehicles can be made lighter and therefore use less fuel.

If it can be implemented without the need for a “standby driver”, there is scope to lower taxi and freight costs substantially. In the latter case this should help make smaller trucks viable, reducing the need for very large trucks within urban areas. However the natural extension of eliminating the need for drivers is to remove the requirement to own cars altogether. If all the functionality of a private car is still possible – like on-demand availability, privacy, point-to-point travel – then the warrant for owning a dedicated vehicle is greatly reduced.

Huge benefits would follow if sharing could be made to work because rather than being parked for 98% of the day, vehicles could be out earning their keep 24/7. The size of the city’s car fleet would be greatly reduced and the cars themselves could be much smaller and lighter – for example, a majority could be single seaters to reflect demand patterns. In time, it’s likely the cost of travel attributable to vehicle ownership and fuel costs would fall significantly as economies of scale were achieved. People on lower incomes or unable to drive would get a big improvement in mobility. Travellers would ‘pay per kilometre’, making them more sensitive to travel costs. Read the rest of this entry »

Is commuting killing us?

Posted: May 30, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic, Public transport | Tags: auto, car, commuting time, Patricia Mokhtarian, Public transport, Richard Florida, transit 8 CommentsLong commutes cause obesity, neck pain, loneliness, divorce, stress, and insomnia. Your commute is in fact killing you, according to this story published in Slate last week. And it’s bad for others too – in his Melbourne address last month, Robert Putnam argued that a ten minute increase in commute time reduces social capital by 10%. Richard Florida says it’s time to put commuting right beside smoking and obesity on the list of priorities for improving the health and well-being of Americans.

I’m always bemused by these sorts of claims. Apart from the fact that the majority of commutes are relatively short, they neglect the salient fact that people spend time commuting because it’s worth it – that’s how they earn their living. And in general, the further they go, the better the job and/or the better the house. Commuting is a bit like having children – it costs a squillion, but for most people it’s worth it!

The reality is that most people prefer to commute some distance. This study of US commuters by Redmond and Mokhtarian found that 42% of their sample are happy with their current commute i.e. their actual travel time and their ‘ideal’ commute time coincide. People seem to like some space between work and home. They found that 7% actually say their commute isn’t long enough!

Nevertheless, the study also found that just over half feel their commute time is too long compared to their ‘ideal’ commute time. That finding, however, doesn’t really say much. The trouble is people don’t make unconstrained judgements like this in real life. If asked, rational people will of course say they would like less of the boring things in life and more of the interesting and exciting things. If they’re not forced explicitly to consider the cost, people will naturally acquiesce when they’re posed questions of this sort. It’s a difficult concept to measure, so a much better guide to commuting time preferences is what people actually choose to do in the face of real-world constraints.

It turns out workers don’t tend to spend inordinate amounts of time commuting. This analysis of US Census data shows that 45% of one-way commutes in US metropolitan areas take less than 20 minutes and only 8% take more than 60 minutes. This US survey found that 81% of commuters spend less than half an hour getting to work. In Melbourne, more than half of all trips to work (54%) take less than 30 minutes. Only 12% of commutes take longer than an hour and only 3% more than 90 minutes.

Having said that, whether or not an hour a day spent commuting to and from work is ‘inordinate’, depends on what it yields. The question can’t be addressed sensibly without considering the benefits as well as the costs. We spend time on a host of activities like sleeping, cooking and taking the kids to sport because we feel they are necessary to derive the associated benefits. Likewise, commuting provides something that’s extremely valuable – income. That’s a basic, a necessity. But work also provides a host of associated benefits like status and social interaction. The bottom line is we commute because it’s worth it – we’ll minimise commute time subject to other constraints but we don’t expect it to cost nothing. Read the rest of this entry »

– Has “peak gasoline” been and gone?

Posted: May 29, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic, Energy & GHG | Tags: carbon emissions, elasticity, energy, John Quiggin, Molly Espey, peak gasoline, peak oil, petrol 4 CommentsOne of the themes I’ve consistently emphasised when discussing looming threats like peak oil is that policy responses must take account of the adaptability of markets and consumers. Drivers will respond to higher petrol prices by, for example, travelling less, changing to smaller fuel-efficient cars and moving to more accessible locations. Manufacturers will respond by producing vehicles that use less fuel and/or alternative fuels.

One of Australia’s leading public intellectuals, left-leaning economist Professor John Quiggin, reckons that “peak gasoline” has in fact already happened. He points to the 8% decline in petrol consumption in the US since 2006 (per capita consumption declined by more than 10%) and, prospectively, to even tighter standards requiring a 40 per cent improvement in the average efficiency of new cars, relative to the existing fleet, by 2016. I’ve previously discussed how the rate of growth in per capita car travel has been slowing for some time in Australia (and other western countries) and has actually declined in recent years.

We know that motorists respond to price increases by reducing petrol consumption. One estimate of the elasticity of demand for petrol in Australia with respect to price is around -0.1 in the short term and -0.3 in the longer term i.e. a 10% increase in the pump price of petrol would initially reduce demand for petrol by 10% 1% and, in the longer run, by 30% 3%. Some of this reduction comes via higher public transport patronage but the vast bulk comes from car-related adaptations like more efficient trip-making and smaller, lighter and more fuel-efficient vehicle.

In the US, this review of hundreds of elasticity coefficients found that the in the short-run, “estimates for the demand for gasoline range from 0 to -1.36, averaging -0.26 with a median of -0.23 for the studies included here. Long-run price elasticity estimates range from 0 to -2.72, averaging -0.58 with a median of -0.43”. So in the longer term (more than a year), US drivers respond to a 10% increase in price by reducing their consumption of petrol, on average, by 58% 5.8%.

Professor Quiggin allows that the GFC has had an effect on travel behaviour in recent years (petrol consumption tends to rise and fall with income) but still thinks that estimates of elasticities for the US are conservative:

I suspect that the full long-run elasticity, including induced innovation, is near 1, meaning that if current real prices are sustained, consumption could fall as much as 70 per cent below the level that would be expected if prices had remained at the 2000 level.

For my money, where the “peak gasoline” hypothesis gets really interesting is his argument that per capita global oil production peaked in 1979, but per capita output of goods and services nevertheless increased substantially over the subsequent 30 years, with the fastest increases in the developed world. In other words, personal living standards increased while personal oil consumption declined. “That seems pretty conclusive as far as apocalyptic versions of the Peak Oil hypothesis are concerned”, he says. Read the rest of this entry »

– Do governments spend too much on roads?

Posted: May 16, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic, Public transport | Tags: ACF, Australia's Public Transport: Investment for a Clean Transport Future, Australian Conservation Foundation, BITRE, Bus Rapid Transit, Commissioner for Sustainability, DART, Doncaster, Funding, Public transport, roads, Smartbus 8 CommentsThe Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) got a lot of press recently with its claim that “governments across Australia are spending at least four times more on building roads and bridges than on public transport infrastructure“.

The claim is in a new ACF report, Australia’s public transport: investment for a clean transport future, which argues for a rebalancing of the transport capital works budget, recommending that “two thirds should be spent on public and active transport measures and one third should be spent on roads”.

I agree with the ACF that more needs to be spent on public transport, but I don’t think the “roads vs public transport“ logic does justice to the complexity of the situation. There are a number of reasons why more public funds are spent constructing roads than rails.

One is that people drive much more than they use public transport. According to the Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE), Australians travel almost eight times as many kilometres by car as they do by bus and rail-based public transport. The money is going where the demand is. If you accept the ACF’s numbers, public transport is actually getting a disproportionate share of public construction expenditure. Roads are needed even if travel is confined to foot and horse-drawn vehicles. The Hoddle grid in Melbourne and the avenues and streets of Manhattan were designed before cars were invented – land has limited value if it can’t be accessed.

Construction expenditure doesn’t in any event tell the whole story. Most funding for public transport comes via operating subsidies. Although getting comparable numbers is hard, Sydney University transport academic, Professor John Stanley, estimates that in states like NSW and Victoria, total public funding for public transport and roads is probably pretty nearly equal. In his 2008 report, Public transport’s role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, Victoria’s Commissioner for Sustainability noted a significant shift in funding priority from roads to public transport at the State level.

Another reason roads are important is for the distribution of freight within the metropolitan area. According to BITRE, the number of tonne kilometres of urban freight transported by road within Australia’s eight capital cities in 2007/08 was more than five times higher than it was in 1971-72. There is simply no practical alternative to road for tasks like restocking those hundreds of supermarkets that supply suburban households with food and household goods.

But most importantly, roads are also extremely important for public transport. For example, in Melbourne, the Doncaster Area Rapid Transit (DART) system, the Airport-CBD Skybus service, and the city’s three new orbital Smartbus transit services, all use buses. Because they use the existing road network, these systems do not require significant new land acquisition and construction. Some trunk lines might in time justify conversion to light rail services as patronage increases, but they too can use existing roads rather than require a dedicated right of way. Read the rest of this entry »

– Can parking be managed better?

Posted: May 12, 2011 Filed under: Cars & traffic | Tags: Donald Shoup, Melbourne City Council, parking, pricing, San Francisco, SFpark 10 CommentsI’m disappointed by the discussion of parking in Melbourne City Council’s draft Transport Strategy Update 2011-2030 (note – it’s a big download). There’s an opportunity to improve the efficiency of parking space allocation through using technology and pricing in combination, but Council seems content to pass on it.

The broad thrust of the discussion in the report is that the number of on-street parking spaces will decline over the next 20 years to enable public transport and amenity improvements to be implemented. Council is mindful of the impact this will have on its own revenues and those of local businesses, but is persuaded by the social and environmental benefits.

A key recommendation in relation to on-street parking is that Council “will implement new parking technology systems that allow payment without requiring parking machines or meters (and) will remotely sense and assess parking occupancy”. Surprisingly, this recommendation is entirely unsupported by any explanation or discussion. As far as it goes, it nevertheless sounds good – it’ll lower costs by eliminating the need for parking inspectors and it’ll give drivers more flexible payment options.

What seems to be missing, though, is the opportunity to provide drivers with real-time information about parking availability. More importantly, it squibs the opportunity to improve efficiency in allocating parking spaces by setting a price that’s responsive to demand.

The current pilot project just introduced in San Francisco, SFpark, gives a sense of what can be done. Like Melbourne City Council’s plan, it involves sensors that automatically sense if a parking space is empty. SFpark however will convey that information to drivers electronically via a smartphone app. That should reduce the time drivers spend cruising for parking. According to Donald Shoup, a Professor at UCLA and the author of The High Cost of Free Parking, several studies have found that cruising for curb parking generates about 30 percent of the traffic in CBDs in the US. He cites a study he did of a 15 block district in Los Angeles where cruising for on-street parking created 950,000 miles of excess vehicle travel per annum, in the process consuming 47,000 gallons of petrol and producing 730 tons of carbon dioxide.

But the real innovation of SFpark is that prices are adjusted in real time in response to rises and falls in demand. The objective is to ensure that, on average, there is at least one vacant space in each city block:

SFpark will adjust meter prices based on demand to encourage drivers to make trips in off-peak hours and to use parking lots and garages. While high-demand spaces will gradually go up in price, other spaces will decrease in cost……Once a space is found, longer time limits and new meters that accept credit and debit cards will make it easier to avoid parking tickets. Read the rest of this entry »