Is there a case for rail to Avalon Airport?

Posted: April 30, 2011 Filed under: Airports & aviation, Public transport | Tags: Avalon Airport, Melbourne airport, rail, Sita Coaches, Skybus, train 12 CommentsOne of the great mysteries of 2010 is why the then Opposition promised to spend taxpayers funds to provide a rail service from the CBD to Avalon Airport. This wasn’t a promise to conduct a study, as was the case with the Doncaster, Rowville and Melbourne Airport rail lines, but a firm commitment to take action, with a minimum of $50 million to be spent in the first term of a Baillieu Government.

I’ve been scratching my head to come up with a rationale for this rail line, which Mr Baillieu says will cost $250 million. As I understand it, the Government will contribute the first $50 million and share the remaining $200 million with the Commonwealth and Lindsay Fox (although the size of each party’s contribution has not been revealed).

It’s hard to believe, with the range of other transport problems confronting Melbourne and a tight budgetary outlook, how this could even be on the table, much less be the Government’s highest priority.

The customary rationale for building a high capacity transport system is that current arrangements are approaching or exceed capacity. When I discussed this proposal during the election campaign last year, I noted there were only around 13 scheduled departures from Avalon on a weekday and that just 1.5 million passengers use the airport annually. This compares with 26 million using Tullamarine.These Airservices Australia figures indicate Melbourne Airport handles over twenty times as many aircraft movements as Avalon. I went on to say:

If an Avalon train service performed at a level comparable with Brisbane’s Airtrain and captured 9% of current passengers, it would only carry 135,000 persons per year (an average of 370 per day). Skybus carries around 2 million passengers per annum.

Sita Coaches currently carries fewer than 200 passengers per day between Avalon and the CBD for $20 each. So on the face of it, it’s hard to see why public funds should be prioritised to an Avalon rail line for any reason whatsoever, much less ahead of Melbourne Airport (which is itself a long way from needing rail at this time).

One argument I’ve heard is that Avalon needs a rail line to expand its air cargo capacity. This sounds particularly unlikely to me. Just why customers would pay a large premium to send high value, low weight, high priority articles by air from interstate and overseas, only to then have them transported from Avalon to the CBD and beyond by rail, is a mystery. Couriers were invented to provide speed, flexibility and demand-responsiveness for just this sort of task. The owner of Avalon might want a rail line, but it’s not apparent that its purpose would primarily be to service air traffic. In any event, I’m not sure it would be a good idea for the taxpayer to fund rail for an airport operated by a company that has its own logistics operation.

Another possible argument for an Avalon rail line might be that Melbourne Airport has capacity constraints. This is probably the least convincing of any rationale. Melbourne Airport’s great advantage, especially compared to its key rival in Sydney, is that it has enormous potential for expansion and no curfew. It has a primary north-south runway and a secondary east-west runway with the potential to accommodate two further runways as well as additional operational areas, terminals, aviation support and commercial facilities. Read the rest of this entry »

What makes great architecture?

Posted: April 27, 2011 Filed under: Architecture & buildings | Tags: Ajay Shah, architecture, China, history, India, Mukesh Ambani 4 CommentsI’ve written the odd bit about architecture and design before (see here) but I always intended to write more. I’d especially like to review buildings, but it’s hard to get any hard information on how buildings perform for their owners and users – that’s one reason why so much architectural writing is either self-serving or vacuous.

So this interesting piece by Indian economist, Ajay Shah, offers another way to approach the subject of architecture. He poses the question: “when and where do great feats of architecture come about?…… Why do some places achieve great feats of architecture, while others routinely opt for merely functional structures?”.

He says that he is instinctively unsatisfied with the claim that the USA lacks great architecture because Americans have poor taste. Instead, he offers the following five explanations for “great feats of architecture”:

Surplus — To go beyond merely functional structures requires resources to spare. At low levels of income, people are likely to merely try to get some land and brick and stone together. In these things, we have nonlinear Engel curves. Pratapgarh looks picayune because Shivaji lacked surplus

The desire to make a statement and to impress — Ozymandius wanted to make a point: He wanted ye Mighty to look at his works and despair. I have often felt this was one of the motivations for the structures on Raisina Hill or the Taj Mahal

Arms races — There may also be an element of an arms race in these things. Perhaps the chaps who built the Qutub Minar (1193-1368) in Delhi set off an arms race, where each new potentate who came along was keen to outdo the achievement of the predecessor. I used to think that the Taj Mahal (1632-1648) was so perfect, that it could not be matched, and thus it put an end to this arms race. But then I saw the Badshahi Mosque in Lahore (1671-1673), and I had to revise my opinion……

Transparency — You only need to impress someone when there is asymmetric information, where that someone does not know how great you are. Shah Jahan needed to build big because the targets of his attention did not know the GDP of his dominion and his tax/GDP ratio. In this age of Forbes league tables, Mukesh Ambani does not need to build a fabulous structure for you to know he’s the richest guy in India. A merely functional house suffices; a great feat of architecture is not undertaken

Accountability — The incremental expense of going from a merely functional structure to a great feat of architecture is generally hard to justify. Hence, one might expect to see more interesting architecture from autocratic places+periods, where decision makers wield discretionary power with weak checks and balances. As an example, I think that Britain had the greatest empire, but the architecture of the European continent is superior: this may have to do with the early flowering of democracy in the UK. Read the rest of this entry »

– What can history teach us about rail?

Posted: April 26, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: history, land boom, Michael Cannon, Outer Circle Railway, rail, The Land Boomers 3 CommentsBack on April 5th I noted that the suburban rail network we have in Melbourne today was substantially in place by the end of the nineteenth century.

I asked why, with the threat of climate change and peak oil hanging over us, we can’t replicate the achievements of the nineteenth century and massively expand Melbourne’s rail network. If our forebears of four or five generations ago could do it, why can’t we, with our superior technology, do even better?

I pointed out – quite accurately as it turned out – that I couldn’t bring an historian’s eye to the subject. I proposed six hypotheses to explain why it would be much harder to build the suburban network today. One of my reasons was that back then the railways covered their operating costs. A reader, Russ, pointed out that the experience in Victoria was quite different:

After the 1880s the government stepped in, and via the combination of rampant corruption and misplaced optimism in the largest real estate bubble in Australian history built 90% of the existing network – most of it completely wasted expenditure.

On his recommendation, I’ve been flipping through The Land Boomers by Michael Cannon. According to Cannon, transport was so vital to Melbourne’s growth that the story of Victorian politics in the 1880s was largely the story of the building of railways:

Hundreds of miles of track, some of it quite useless, pushed out from the egocentric city to the rampant suburbs and the far countryside. Hardly a member of Parliament whose vote could be bought went without his bribe in the form of a new railway, a spur line, or advance information on governmental plans to enable him to buy choice land in advance – the value of which was enormously enhanced when the line went through. It was a dispiriting chapter in Victorian political morality. Read the rest of this entry »

Melbourne ‘fantasy rail map’

Posted: April 25, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: fantasy map, future, rail, Railpage, train 5 CommentsAs it’s the holidays I thought I’d show this 2009 map I stumbled across at Railpage. This is an example of the growing genre of ‘fantasy maps’, fed no doubt by easy access to GIS. It’s one person’s vision of what Melbourne’s rail system could look like at some point in the future at an unspecified financial and political cost. What distinguishes this one from the flotsam is the way the author has used the same graphic style as the current Metlink map, which you can see here.

It doesn’t have the new line to Avalon Airport the Government has committed itself to, perhaps because no one ever conceived in 2009 that it could ever be a priority. But it does have the now well known new lines to Melbourne Airport, Rowville and Doncaster, the latter extended to Donvale in the east, and via Fitzroy in the west to connect to the Melbourne Metro link from the west at Parkville. The Metro carries on via Swanston St to the Domain and St Kilda and connects to the Sandringham line at Ripponlea and the Dandenong line at Caulfield.

The map shows the Regional Rail Link as well as a branch line to Aurora and extensions of existing lines to Whittlesea, Yarra Glen and Clyde. The Glen Waverley line is extended via Knox to connect to the Belgrave line. The Alamein line is extended to connect with the Glen Waverley line and onto the Dandenong line via Chadstone. The Upfield line connects to the Craigieburn line at Roxburgh Park. All lines appear to be fully electrified and the number of tracks is increased to expand capacity on a number of existing lines.

The curmudgeons at Railpage have picked up on a few oddities (Rushall a Premium Station!?), but what I find amusing is that Doncaster is shown in Zone 2! I’m not expecting to see that in any of the PR material associated with the Government’s feasiblity study. Also, a traveller can get as far as Airport West on a Zone 1 ticket, but the Airport is Zone 2. And to go from the Airport to Keilor West is a Zone 1-2!

These are mere details in a ‘fantasy map’ but they illustrate some of the anomalies with Melbourne’s zonal fare system that I discussed last week.

Are Melbourne’s houses too big?

Posted: April 20, 2011 Filed under: Housing | Tags: Building Commission, dwelling size, empty nester, floor space, growth area, Metricon, Robie House 17 CommentsAccording to the State’s Building Commission, new houses in Victoria were 252 m2 on average in 2008-09 compared with 217 m2 in 2000-01. This report says “homes in Victoria are getting bigger, much bigger – leading to warnings that some people may be building homes bigger than they need by borrowing more than they can afford”. The Building Commissioner is quoted as saying:

The promotion of larger homes by medium and high volume builders, where added rooms are used as a marketing tool, have contributed to the increase in size……consumers are up-sold to home theatres, additional bathrooms and media rooms

I have a couple of thoughts/reactions to this.

First, some context – while there are buyers who want a behemoth like Metricon’s 49 square ‘Monarch’, almost three quarters (74%) of Growth Area buyers purchase a single level dwelling. Moreover, 70% of homes are less than 30 squares and 47% are less than 26 squares. Some are buying a “McMansion”, but most are buying something like Metricon’s Grandview.

Second, the claim that buyers are so gullible they are “upsold” to bigger homes they don’t “need” is patronising. Buyers do know what they want. Two thirds of Growth Area purchasers are buying their second home – half of this group are buying their third or fourth home. And nearly half (48%) of adult buyers in the Growth Areas are aged 35 years or more.

Third, if people are buying homes they can’t afford, that’s not primarily an issue of dwelling size. I expect over-stretched buyers would more likely be purchasing a home that’s closer to the city centre — it would be smaller than a fringe “McMansion” but cost more because of its greater accessibility. If there has been an upward movement in the proportion of people buying homes they can’t afford, the problem and the solution lie with lending policies rather than with dwelling size. Read the rest of this entry »

Is the proposed airport train off the rails?

Posted: April 19, 2011 Filed under: Airports & aviation, Public transport | Tags: High Speed Rail, Melbourne airport, RACV, Skybus, The Age, train 10 CommentsThe idea of a high-speed Melbourne Airport-to-CBD rail line is in the news yet again, this time advocated by the RACV.

You’ve got to give the Royal Automobile Club of Victoria its due. While simultaneously calling for roadworks to reduce congestion and improvements to traffic flow in Hoddle Street, it’s morphing into a general transport lobby group that “advocates improved transport services for all its members, including those who use public transport”.

This story on the RACV’s call for an airport train has attracted over 100 comments, most of them favouring a rail line. There’re the same themes that come up every time The Age runs pro-airport rail stories – it’s embarrassing that Melbourne doesn’t have a dedicated rail line; car parking prices at the airport are extortionary; Skybus fares cost an arm and a leg; the contract with Citylink won’t allow competition; and the airport and taxi industry won’t let anyone kill their golden goose.

Even while they approvingly cite the example of Sydney’s and Brisbane’s airport trains, commenters nevertheless generally assume an airport train would be high speed, would solve congestion on Melbourne’s freeways and would cost no more than a Zone 1-2 fare.

I’ve explained before why an airport rail line is unlikely to make sense for a while yet, but it’s a good idea to take another more considered view of its prospects than those advanced by unabashed boosters. Here’re twelve reasons why a rail line to Melbourne Airport is unlikely to make sense for a while yet.

First, Skybus already provides a dedicated public transport service from the airport to the CBD with higher frequencies and longer span of hours than any train service in Melbourne. Most times trips to Southern Cross station take 20 minutes. While they blow out to over 40 minutes in peak hour, that could be addressed for a fraction of the cost of a new rail line by extending the existing dedicated on-road lane to other sections of the route that are prone to congestion.

Second, there’s little to be gained from spending more than a billion dollars to replace a high quality public transport service (Skybus) with another one (train), when the money could be spent on providing better public transport to areas that don’t currently have adequate service.

Third, every study undertaken to date has concluded that a rail service isn’t warranted. It might be in the future but not yet. In the meantime, there is considerable potential to increase the capacity and speed of Skybus. As pointed out here, Brisbane’s south-east busway already carries 15,000 passengers per hour. Read the rest of this entry »

Should fare zones be rationalised?

Posted: April 16, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: buses, fares, Public transport, rail, trains, transit, zones 18 Comments I like the principle underlying Melbourne’s two zone public transport fares system – if you travel further, you pay more. Travel within roughly 11 km of Flinders St Station is a Zone 1 fare and travel within the area beyond that is a Zone 2 fare. Those who travel between zones pay a Zone 1-2 fare. Sensibly, there’s a three station ‘grace’ overlap between zones.

I like the principle underlying Melbourne’s two zone public transport fares system – if you travel further, you pay more. Travel within roughly 11 km of Flinders St Station is a Zone 1 fare and travel within the area beyond that is a Zone 2 fare. Those who travel between zones pay a Zone 1-2 fare. Sensibly, there’s a three station ‘grace’ overlap between zones.

The logic of the tariff is premised on the idea that trips are to the CBD. If you live in Epping (say), you are 19 km from the CBD and in Zone 2, whereas someone living near Bell station in Preston is only 9 km out and is in Zone 1. The standard Two Hour Zone 1 fare is $3.80 and the Zone 2 fare is $2.90. If you cross zones, the fare for the longer distances expected with Zone 1-2 trips is $6.00.

That all sounds good, but inevitably there are anomalies. For example, a traveller boarding a train on the Epping line at Reservoir station can travel through 15 stations to Flinders St for a Zone 1 fare. However anyone boarding at the next station out, Ruthven, must pay a Zone 1-2 fare to travel to Flinders St.

Residents who live near the overlap stations and make short trips face a very high marginal cost. For example, someone boarding at Bell station on the Epping line can only travel 3 stations away from the CBD before incurring a Zone 1-2 fare. Similarly the four station inbound trip from Ruthven station to Bell is a Zone 1-2 fare. The same pattern happens on other lines.

Another anomaly is the cost of Zone 1-2 fares compared to Zone 1 and Zone 2 fares. With so much of the cost of operating a rail service tied up in capital items, it’s hard to see why a Zone 1-2 fare costs 60% more than a Zone 1 fare and over 100% more than a Zone 2 fare. That might possibly make sense for buses but seems a real stretch for trains.

These sorts of anomalies could be seen as unfortunate but inevitable compromises – after all, most travellers are bound for the city centre. However as discussed here, the great bulk of jobs are now in the suburbs, not the CBD. Moreover, most Melburnians live relatively close to their key travel destinations, usually in the same or a contiguous municipality.

We should expect that public transport travellers will increasingly be seeking to make intra-suburban trips via a grid of well coordinated train and bus services. Indeed, many advocate such an approach. A two-part tariff based on distance from the CBD makes less sense in that situation. While the CBD will remain the main market for trains for a considerable time yet, they nevertheless are likely to have a growing role in intra-suburban travel. Policy-makers should be thinking about how to make them work harder in this role. Read the rest of this entry »

– How should transit proposals be evaluated?

Posted: April 13, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: benefit-cost analysis, Lisa Schweitzer, Peter Gordon, Public Works Management and Policy, Robert Cervero, University of Southern California, Urban rail transit 6 Comments

How your parents raised you had almost nil effect on you, according to Bryan Caplan, Professor of Economics at George Mason University. A fascinating presentation!

There’s an interesting debate in the latest issue of one of the academic journals about the application of benefit-cost analysis to urban rail transit projects in the US. The principal players are all from various campuses of the University of Southern California – Peter Gordon, Robert Cervero and Lisa Schweitzer. The journal is Public Works Management and Policy (PWMP), a “peer-reviewed journal for academics and practitioners in public works and the public and private infrastructure industries”. The editor summarises the positions of the protagonists:

Peter Gordon and Paige Kolesar have written A Note on Rail Transit Cost-Benefit Analysis: Do Nonuser Benefits Make a Difference? which examines the rather poor performance of modern rail transit projects when measured in traditional benefit-cost terms. In counterpoint, Robert Cervero and Erick Guerra offer To t or not to t: A Ballpark Assessment of the Costs and Benefits of Urban Rail Transportation where they argue that the benefits of urban rail accumulate over long time horizons and to many who will never use the system. This is a new version of an old conversation and Lisa Schweitzer serves as a referee of sorts with Benefit-Cost Analysis of Rail Projects: A Commentary.

The full articles are gated but the links above provide the abstracts for the Gordon and the Cervero articles. There’s no abstract for Schweitzer’s commentary, however because it’s quite short (2½ pages in the journal), can be read independently and is very good, I’ve posted her piece here complete. She’s a smart, independent and sensible observer of transport issues and I agree with most of her comments in this paper. Like us, the US has some good transit projects, but there are also some that are highly questionable.

The debate in this issue of PWMP reflects a hardy perennial in the transportation community. With some consistency, rail transit fails to meet benefit–cost criteria or ridership forecasts. Planners and transit advocates—often these are the same—respond that benefit-cost analysis is only a partial measure of a project’s worthiness. How, they ask, do you monetize the benefits of something like a trolley that reinvigorates a slumping downtown? Some of the things we could never imagine living without—like the Brooklyn Bridge—would probably have failed a benefit–cost test back in 1866when the New York legislature authorized it. And now the bridge is an architectural icon in a region whose economic health has come to rely at least in part on the aesthetics of investments made more than a century ago. Read the rest of this entry »

Why do we dislike buses?

Posted: April 11, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: bus, DART, Doncaster, Melbourne airport, Public transport, transit 18 CommentsMelburnian’s seem to love trains and dislike buses. Melbourne Airport and Doncaster are both served by high-frequency bus services with a wide span of operating hours, yet large numbers of people want to spend billions replacing them with trains.

The list of criticisms of buses – relative to trains – is long. Right at the top is slowness. Buses operate in traffic, follow circuitous routes, stop frequently and idle while passengers dig out spare change to pay the driver. They’re uncomfortable too. Shelters are perfunctory, the ride is jerky and difficult if standing, seats are jammed too close together and too many drivers don’t seem to actually like passengers. And buses are unreliable. They’re invariably late and if you miss one the wait for the next one will seem interminable. If it’s night or a weekend there’s a good chance that was the last bus for the day.

Then there are systemic criticisms. Buses aren’t ‘legible’ — prospective passengers can’t see where the route goes. Sometimes routes vary over the course of a day. Buses are also impermanent. Developers are less inclined to risk investing along a route if it can be changed overnight or even removed. And there’re hard-nosed criticisms, too. Buses don’t carry many passengers. Operating costs are high because each vehicles requires a driver. Per capita GHG emissions and energy consumption are no better than cars. Engines are noisy and polluting.

As things stand, buses look pretty bad compared to trains, even given the unreliability and crowding that characterises peak hour train services in many Australian cities. Buses have a serious image problem, not just here but in many western cities.

But it’s an unfair comparison*. The key reason buses are perceived so poorly relative to rail is they are mostly assigned to marginal routes with low patronage. Operators follow indirect routes and stop frequently to maximise revenue; they reduce frequency and hours of operation to minimise costs. They can do that because their customers aren’t usually sophisticated CBD workers but travellers who are mostly “captive” to public transport. In other words buses mostly operate in a different market to trains. But it’s given them a bad reputation.

Most of the criticisms can be fully addressed, or at least softened, when the comparison is like-for-like i.e. when buses operate the sorts of long-haul commuter services that urban rail is customarily used for in Australia. Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems typically have high patronage and operate in their own right of way (just like trains) or in dedicated on-road bus lanes. Stops are major interchanges spaced kilometres apart and tickets are bought before entry.

BRT vehicles can be made with the internal look and ‘feel’ of (light) rail and the jerky ride can be minimised with electric engines. Articulated buses carry large numbers of passengers and can provide better leg room. According to Corinne Mulley, Chair in Public Transport at Sydney University, Brisbane’s South East Busway carries 15,000 passengers per hour and in Bogota buses carry 45,000 per hour. She says “US evidence points to infrastructure costs for dedicated buses being approximately one third of light rail costs”. As a point of reference, Eddington forecast that a Doncaster rail line would carry up to 12,250 one-way trips per day. Read the rest of this entry »

Why are we still so focussed on CBD rail?

Posted: April 10, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: Doncaster, Melbourne airport, Public transport, rail, Rowville, trains 19 CommentsIt’s bizarre, but much of the contemporary debate about expanding public transport in Melbourne is focussed on building more rail lines to the CBD even though the great bulk of jobs are now in the suburbs. It seems we’re locked in an old way of thinking when the world long ago moved on to doing things in a very different way.

The proposed Rowville, Doncaster and Melbourne Airport rail lines are evidence of our preoccupation with radial train lines. They were key issues during last year’s election campaign and the Government promised to study the feasibility of all three. They all connect to the CBD. No one refers to any of them as, for example, the proposed “Rowville to CBD” rail line – the debate is so CBD-centric that’s taken for granted.

Yet the city centre now has only a fraction of all jobs in the metropolitan area. The traditional CBD – that area bounded by Spring, Flinders, Spencer and La Trobe streets – has just 10% of all jobs in Melbourne, as mentioned here. Even the entire City of Melbourne municipality has only 19% of metropolitan jobs.

But it’s not just jobs (although they’re very important because that’s where rail does best). The vast bulk of travel by Melburnians for non-work purposes – which involves considerably more trips than the journey to work – is also not directed at the city centre. It’s local and over relatively short distances.

One consequence of this ‘radial thinking’ mindset is the popular sentiment that ‘black holes’ in the network, like Doncaster, have to be ‘filled in’ with new rail lines to the CBD. This is despite the likelihood that the justification for a Doncaster-CBD line borders on the farcical. For example, Eddington estimated that only 8,500 workers living in the municipality of Manningham commute to the City of Melbourne, of whom 3,150 already take public transport (and this was before the new DART bus rapid transit system started!).

With 72% of jobs located more than 5 km from the CBD and 50% more than 13 km, it’s surprising that the focus of public transport expansion isn’t on improving services for cross-suburban travel. Why, for example, isn’t there more emphasis on improving suburban orbital services and feeder services to major suburban destinations?

The fact is Melbourne’s radial train system was never intended to deliver workers to suburban jobs. The existing rail lines are the ‘spokes’ in a radial system that’s designed for the high peak loadings generated by the CBD. In contrast, economic activity in Melbourne’s suburbs is quite dispersed – no more than 20% of suburban jobs are in the largest 31 activity centres – so something far more flexible than commuter heavy rail is likely to be required. Read the rest of this entry »

How do world transit systems compare?

Posted: April 7, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: maps, Public transport, subways, transit 12 CommentsThis is an eye-opener. First thing you need to do is go here where artist and urban planner Neil Freeman has prepared maps of many more cities at the same scale (none from Australia unfortunately). What these maps show is the enormous variation in the scale and density of different systems. No doubt the artist has had to make assumptions about what to include and exclude*, but this is nevertheless very important information to bear in mind when comparing the performance of Australian rail networks with systems elsewhere.

I think Melbourne’s rail system is a leviathan compared to some of these e.g. the networks in Toronto, Vancouver, Amsterdam, Budapest and Brussels. Note the scale (5 km) beside the map of Toronto above. As a point of reference, it’s about 5 km as the crow flies from Flinders St station to Merri station on the Epping line, Hawthorne station on the Lilydale line and Newmarket station on the Broadmeadows line. Five kilometres is the boundary of the inner city. Read the rest of this entry »

– Are cars the key challenge?

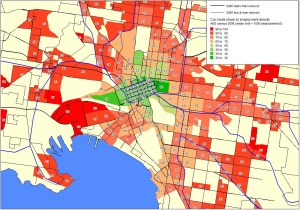

Posted: April 6, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: Cars, journey to work, mode split, Public transport, transit 17 CommentsThe accompanying map from Charting Transport shows the proportion of journeys to work in Melbourne’s inner city undertaken by car in 2006 — the rest were by public transport, walking and cycling (note that green denotes a low share for cars and red a high share*).

There is a clearly defined area — the ‘golden mile’, bounded by Spring, Flinders, Spencer and La Trobe — where cars capture less than 30% of all journeys. Around Swanston Street the share of journeys taken by car is as low as 24% (click to enlarge map).

But the really striking thing to my mind is the steep increase in car’s mode share as soon as you move beyond walking distance of the rail loop. You only have to go as far as the northern side of Victoria Parade and that share jumps to 50– 60%. Go toward the Hoddle Street end and it’s more than 70%. Once you get into the suburbs, most employment concentrations have a mode split that is 80% – 90% car.

One interpretation of the data is that sustainable modes are doing pretty well in the golden mile. Another is that they’re not doing well enough – maybe no more than 10% of journeys should be considered the ‘natural’ share of the car in this sort of key business area – and hence there’s an opportunity for public transport to increase its share.

I incline to the latter view, but I think there’s another interpretation of this data that’s arguably more significant. Consider what it takes, in terms of density and transit supply, to get the share of journeys to work by car down below 30%.

The ‘golden mile’ is just 2 km2 out of a built up area of around 2,500 km2 (the entire MSD is over 7,500 km2). That little area is the largest single concentration of jobs, by far, in the metropolitan area. It accounts for 10% of all metropolitan employment and is denser by an order of magnitude than any other activity centre in Melbourne, as exemplified by the number of very tall buildings it contains. And despite its diminutive size, it’s the focus of the entire metropolitan train and tram systems. It’s the ‘hub’ where all the ‘spokes’ meet – a giant transport interchange – and is accordingly, again by an order of magnitude, the most accessible place in Melbourne by public transport.

Yet for all the astonishing advantages of job density and public transport quality, a quarter to a third of all those who work in this tiny area still drive to work. Further, literally within one or two blocks of the rail loop, the car’s share of journeys to work rises to 50% and more, notwithstanding that these near-CBD areas themselves have a job density and level of public transport service that is far higher than the rest of the metropolitan area. And this is the journey to work – the trip most likely to be taken by public transport! Read the rest of this entry »

Why can’t we have more train lines?

Posted: April 5, 2011 Filed under: Public transport | Tags: 1890, history, railways, trains 11 CommentsBy the time of the economic depression in 1891, Melbourne and Victoria already had an impressive network of railway lines. The last significant addition to the metropolitan rail system – the Glen Waverley line – was built in 1930, just before the Great Depression.

It’s reasonable to ask why, with the threat of climate change and peak oil hanging over us, we can’t replicate the achievements of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and massively expand Melbourne’s rail network. If our forebears of four or five generations ago could do it, why can’t we — with our superior technology — do even better?

I think the answer is that circumstances were vastly different then and much more sympathetic to constructing a network of rail lines. I can’t bring an historian’s eye to this topic but here are some of the broad ways – consider them as hypotheses – in which I think the great rail-building era differed from today.

First, train patronage was very high in that era. Virtually everyone relied on trains to travel any sort of distance. The proportion of the metropolitan population that lived and/or worked in the inner city where rail access was best was much larger than today. Hence there was a real will to build rail lines.

Second, the railways covered their operating costs. All of the first lines built in the 1850s from Melbourne to the suburbs were financed by private money. I don’t know when it happened in Australian cities, but US railways weren’t subsidised directly until after the second world war. If lines are profitable – or at least cover their operating costs – getting funding for expansion of networks and services is much easier.

Third, competition was limited. Investors in rail, whether private or public, had to compete with horses and in some localities with trams, but they had nothing like the competition that contemporary rail lines get from cars. The widespread market penetration of cars, especially after world war two, strangled the demand for train travel in Melbourne, reducing it’s share of motorised travel to around 10%.

Fourth, many Melbourne train lines also extended beyond the metropolitan boundary to country areas and interstate. They did double duty, carrying not only suburban commuters but also country freight and passengers. As this was an era when a much higher proportion of the nation’s population lived in the country, it would have made the case for building new lines right into the heart of Melbourne considerably stronger. Of course, country trains didn’t have to compete against trucks or planes, either. Read the rest of this entry »

– When is a building worth protecting?

Posted: April 4, 2011 Filed under: Architecture & buildings | Tags: AMPOL, architecture, Elizabeth Tower Motor Lodge, heritage, historic building, National Trust, VCAT 6 CommentsThe planning Tribunal’s decision on the former AMPOL building highlights a couple of issues about preserving significant buildings. In reaching its decision that demolition could proceed, VCAT’s thinking was that ”a greater community benefit for present and future generations will ensue from the establishment of the Peter Doherty Institute than from retention of the former Ampol House”.

I think this highlights a couple of issues over and above what I discussed last time. It implicitly says that what a building is worth is a function of what’s planned to replace it. We now know VCAT doesn’t think the AMPOL building is worth preserving when the alternative use is an immunology and infectious diseases research centre, but what if the alternative were (say) an apartment or office building? Might VCAT have concluded under those circumstances that AMPOL house is in fact worth saving?

It seems to me that if a building truly is worth protecting (a broader ambit than ‘preserving’) on the basis of its architectural and/or historical significance then it is, by definition, worth saving. That value has nothing to do with alternative uses (they’re about the land it’s sitting on, not the building itself). A significant building isn’t any less valuable if the proposed alternative use is something worthy — like a park, social housing, a memorial, a shrine, a research centre — than it is if the alternative is something prosaic, like a car showroom, a shop or apartments.

If planning schemes weren’t muddled with so many “it depends”, there might be less money and time wasted on court battles. If there were a clear statement of what must be protected, councils would have to think a lot more rigorously about what is worth protecting and what isn’t. Developers, owners and the wider community might appreciate clearer guidance.

Another issue the VCAT decision highlights in my view is that understanding the social costs of preservation (or other regulations, like height limits) is too often overlooked. That’s not saying we shouldn’t protect appropriate buildings, but we should know what it’s costing and we should know who’s paying. Read the rest of this entry »

Should the old AMPOL building be demolished?

Posted: April 3, 2011 Filed under: Architecture & buildings | Tags: AMPOL, architecture, Elizabeth Tower Motor Lodge, heritage, historic buildings, immunology, Melbourne City Council, National Trust, Peter Doherty Institute, research 19 CommentsThe key issue arising from the Elizabeth Tower Motor Lodge case isn’t that the building can now be demolished, but rather what’s proposed to replace it.

The former AMPOL headquarters building is noted for its dramatic circular staircase, but its claims to historical significance aren’t compelling. According to the National Trust:

Historically, it is of interest as a building that is designed in a style that appears to belong to the early modernist period of twenty years previously, and is by far the last major building designed in this tradition in Victoria. It is also of interest as the headquarters of one of the major petrol companies in Victoria, which were all undergoing great expansion at that time, and for originally incorporating a petrol station at the ground level.

So, it is the last building designed in a style that was already passé when it was constructed in 1958. And the fact that it was occupied by a major corporation – even a petrol company – shouldn’t be surprising for a building located in the city centre. That’s possibly fascinating, but it’s not the sort of history that justifies preservation when there are alternative uses for the site.

Appearance is always a very subjective topic, but to my eye and, it seems, many others, the staircase is interesting. It’s a sort of melange of Russian Constructivism meets Disney Tomorrowland. Some have labelled it (wrongly) as ‘iconic’. But as visually arresting as it is to the citizens of 2011, it’s neither architecturally nor historically an especially significant staircase.

In fact I suspect it’s much more attractive to contemporary sensibilities that it ever was in its day (would Robin Boyd have labelled the staircase Austerican featurism?). That however is not a compelling reason for preservation because ‘interesting’ looking buildings needn’t be in short supply – we can always build new ones, maybe even more interesting ones.

Stripped of the bunkum about ‘significance’, the streetscape would be no worse off if Elizabeth Tower were replaced by a building that is at least as visually interesting. And that brings us to the core issue – judging by the only picture I could find of it (see picture under fold), the appearance of the proposed replacement building is, to put it nicely, a little bland compared to that dramatic staircase. I’ve no reason to doubt the new building is a tour de force in all other respects and a credit to its designers, but it will inevitably be compared to its predecessor and on that score it appears somewhat underwhelming.