What is the key challenge for cycling policy?

Posted: August 3, 2011 Filed under: Cycling | Tags: bicycles, Bojun Björkman-Chiswell, Cycle Chic, Cycling, license, mandatory helmet, pedestrians, registration, safety 26 CommentsThere’s been a spirited and useful debate in Victoria over the last 12 months about the rights and wrongs of mandatory helmets, but now it’s time to move on to the main game. This column in The Age (and especially the associated comments) by Bojun Björkman-Chiswell, the founder of website Melbourne Cycle Chic, is a reminder that compulsory helmets aren’t the key obstacle to the wider uptake of cycling in Melbourne.

Ms Björkman-Chiswell describes how she was recently hit by a car while cycling in the very city that only days before had been pronounced by Lord Mayor Robert Doyle and Premier Ted Baillieu as a ”bike city”. Melbourne is most definitely not, she avers, a bike city. “It is a city where people who wish to use a fast, free, non-polluting, peaceful and convenient mode of transport are subjected to harassment, culpable driving, injury and death….”.

The shit hit the fan however when she let on, seemingly as an afterthought, that she wasn’t wearing a helmet:

You’ll be pleased to know, Cr Doyle and Mr Baillieu, that despite my accident, my head is fine, but my neck is wrenched, my ankle swollen, my knee strained and my left shoulder, rib cage and thigh bruised, and I don’t wear a helmet.

A string of commenters took her to task for those last five words. As one said: “Great article, but you totally lost all your cred without the helmet. No wonder motorists don’t take you seriously”. And another: “How sad that you won’t protect yourself when you KNOW how idiotic most of the car drivers are”. And this one: “You’re insane if you don’t wear a helmet riding a bike in any Australian city (this isn’t the Netherlands). Plus there is the little matter that it is illegal not to wear a helmet”.

The key issue at the moment for Melburnians interested in cycling isn’t compulsory helmets – that’s a sideshow – it’s safety. While the weight of evidence suggests the exercise disincentive effect of helmets probably outweighs their protective benefits, our starting point is not an ideal world. Melbourne’s streets are dominated by cars. An individual contemplating cycling on the city’s roads has to have very special regard for the dangers of traffic. Cycling might not be as dangerous as people imagine, but it’s the perception of danger that holds prospective cyclists back.

Even if helmets were made discretionary, my feeling is the great bulk of Melbourne’s cyclists would make the rational decision and elect to wear a helmet. Just as importantly, I suspect that the next ‘cohort’ on the verge of taking up cycling (given an appropriate nudge) would also overwhelmingly choose to wear a helmet. Some might prefer not to, but on Melbourne’s roads you need every little advantage you can get.

As Paul Keating might say, compulsory helmets is a second order issue at this time. So let’s move on and give much-needed attention to the current number one issue, improving safety. So far that’s mainly meant providing dedicated infrastructure like bike lanes. More infrastructure is indeed needed – much more – but the task of effectively segregating bicycles and motorised traffic is mammoth.

The reality is cycling can only increase its share of travel significantly in Melbourne if it shares road space with cars, buses, trucks and trams. What’s really needed to make cycling safer is more respect and consideration from drivers.

The core issue is drivers don’t see cyclists as legitimate road users. I don’t think that’s got a lot to do with cyclists not being licensed, bicycles not being registered, riders wearing lycra, or cyclists flouting the road rules. I think its fundamentally because motorists simply see roads as exclusively for their use and cyclists, like pedestrians, don’t belong on them. That’s what drivers have always been told and that’s what they’ve always believed.

What we need now, I think, is a clear and authoritative message from the Government that the roads belong as much to cyclists as they do to drivers of vehicles. The traditional view of motorists about who “owns” the road needs to be drastically reformed. The message needs to emphasise that not only do cyclists have an equal right to the road, their vulnerability means they have a further right to special care and consideration from drivers.

I’d like to see this message promoted strongly in the driver licensing process, in schools and in the media. I’d like to see it underlined by highly visible changes in the law to emphasise drivers’ duty of care toward cyclists. Lawyers might say the law already provides for this – even so, I think there’s a lot to be said for the symbolism of legislation, even if in substance it’s only tinkering at the edges. And of course I’d like to see concerted action by Police to enforce the law when drivers behave carelessly or aggressively toward cyclists.

I imagine a culture where every driver automatically assumes there’s a good chance a cyclist might fall off or do something stupid and makes sure there’s adequate margin to avoid an accident. In reality the probability of an accident is very low, but the consequence is potentially catastrophic. And anyway, it makes the cyclist’s experience less stressful when cars give them a wide berth.

Cyclists have a negligible impact on vehicle speeds at the moment, but if the number of riders increases significantly then this could become a serious issue for motorists. We assume the resulting economic losses are offset or exceeded by the social benefits of cycling. A key challenge however will be to convince motorists that the appropriate speed in a particular situation is defined by the slowest and most vulnerable road user – much as drivers observe 10 kph limits in pedestrian-oriented areas like caravan parks – not by an upper limit.

It can be argued the mandatory helmet law is a key safety issue because it deters some riders and so lessens critical mass. I think it’s a fair argument but I don’t think it’s anywhere near as large a disincentive to cycling as driver behaviour. It’s a fight more likely to be won, I think, when cycling is generally perceived as far safer than it is today.

_____________________________

BOOK GIVEAWAY: follow this link to enter the competition to win a copy of Sophie Cunningham’s fabulous book, Melbourne. Entries close Saturday 13 August.

You are spot on. As a regular road cyclist I am regularly appalled at the lack of care and sometimes (rarely but sometimes) obvious, intentional and dangerous harassment by drivers. Organizations like the Amy Gillett Foundation can only do so much, I think you’re right when you say the message ha to be from the authorities and widely publicized in the media. I would have liked to have seen more positive action from the government with their carbon tax legislation to support cycling as an environmentally friendly mode of transport.

Has AGF achieved change to laws making cycling ‘safer’? In any event, is this the way to make it a safer activity, or is it by the provision of infrastructure, meaning more cyclists, and/or road user laws?

Good point. I wouldn’t advocate people ride on the roads without a helmet. I have had a few close calls in the last year with motorists that didn’t see me, mainly because they don’t expect bikes and aren’t looking for them – even on roads where there are bike lanes. I have flashing lights and high vis gear on but some drivers just don’t see anything except cars and trucks and have made right hand turns across my path. Maybe if more cyclists where out there drivers might start to notice and expect bikes.

quote: Cyclists have a negligible impact on vehicle speeds at the moment – what do you mean?

Bikes are slowing traffic? or More bikes, less cars, faster traffic? My feeling is that the second hypothesis is correct, but perhaps you have evidence that shows otherwise.

And what economic losses are you referring to – drivers pissing away an extra couple of minutes of their lives in a steel box? what about the poor buggers on public transport that are delayed because of car-induced traffic congestion and under-investment in PT infrastructure? Goods and services delivery are also inconvenienced by mum’s taxis, company cars and private vehicles than bikes – we all pay those extra costs.

Private car ownership is toxic; come the revolution, comrade…

Alan, one of the things I’d like to see in Melbourne, that Copenhagen does, is conduct an annual random survey on cycling attitudes. They have, rightly, recognised that the key issue in attracting more riders is not safety as much as perception of safety. And while they go hand in hand, it would be useful to see what percentage of people would ride if they thought it was safe, and what degree of visible improvements need to be made to shift that perception.

Like mdonnellan, I’d also question whether cyclists can slow traffic speeds to a noticeable extent. If roads are sufficiently congested that a car has to wait for cyclists, then their travel time is already (and will continue to be) defined by the time spent queuing at traffic lights. But again, perception of speed matters. Drivers desperately need educating both in relation to cyclists and other motorists that waiting a couple of seconds will have no major bearing on the time they spend travelling. The vast majority of near misses I’ve had on the bike relate to drivers trying to find gaps in front of or next to me that aren’t there, but would be in a few seconds.

I don’t accept that the current level of cycling slows motorists to any great extent. Nor are much larger numbers of cyclists going to slow drivers in situations where there’s already congestion. But most car trips aren’t made in congested conditions – that’s where large numbers of cyclists will increase motorists’ average trip time (I drove in China 20 years ago where I saw this effect).

And as you say, perceptions matter. Even in congested conditions, there are often short sections where speeds are higher – some motorists resent cyclists in these sorts of situations, even though patiently proceeding at the cyclist’s pace would make bugger all difference to their average speed.

Good post Alan.

Safety isn’t just about perception. I did some digging for fatality rates some years ago, posted here: http://www.danielbowen.com/2008/05/08/i-like-cycling-but/ — there might be some better/more up-to-date figures around the place now.

I agree that drivers attitudes do need to change, and I wholeheartedly agree that a legislation change could help facilitate this. Essentially I believe legislation should be enacted that clearly defines that when travelling via any means (driving, cycling, skateboarding, motorcycles, walking, running, anything) the onus will fall on the less vulnerable user to ensure the more vulnerable user is safe and feels safe.

This means when you’re jogging in a park, you’re responsible to ensure you don’t step on a child. When you’re driving a car you’re responsible to ensure you don’t hit or even come to close to a bike, cyclist, etc. If you’re on a bike you’re responsible to not hit a pedestrian or ride too fast in areas that are dominated by pedestrians.

All this said, its not just the attitudes of car drivers that needs to change. Its also the attitudes of people building our roads and bike paths. Bike paths are not treated seriously, and bike are treated as afterthoughts for most road projects.

Last year the intersection where Westgarth Street meets Heidelberg Road had traffic lights installed. Whilst this was a major upgrade that provided a lot of good, the traffic lights were set up in such a way that when heading north east along Heidelberg Road and you came to a stop at the lights on your bike, if you stopped your bike in the designated area (in front of the cars, as it should be) you’d be situated directly below the only traffic lights. From this vantage point you couldn’t tell the lights had gone green until cars started beeping you from behind. Thankfully after a letter to VicRoads they added another light. Although its a strange set-up simply being a single green light attached to the pedestrian crossing light across the intersection.

Another example was the bike path along Merri Parade in Northcote. When the path was initially laid down there was a part where the path was designed to split in two, with one longer route designed to meet another bike path, but both parts reconnecting at the same place. Unfortunately only the longer route was ever paved, despite the “joining” bits clearly showing where the shorter path should have been laid. It stayed like that for over a year, and only when it hit election time in a vulnerable seat, after I confronted Fiona Richardson did any assurances come out that it would be completed. Before this all we’d heard was how the fantastic new bike path had been completed.

How many roads in the urban area go unsealed for over 12 months? I’d be betting on zero. Yet for bike paths, as long as the cyclists can get around by going the long way, that’s good enough.

Until the attitudes of the people building roads changes, I can’t see the attitudes of the people using them changing much either. As you say, drivers have been told for decades they own the roads, they’re still being told this now.

As you note, cycling isn’t particularly dangerous, and that the issue stopping people from cycling is perceived safety rather than actual safety.

So we need to increase “perceived safety” rather than actual safety, and the best way to do that is by building an extensive network of separated cycleways throughout the city. That’s the only thing that will create large enough numbers of cyclists that those streets without cycleways will be calmed by overwhelming cyclist numbers.

Obviously that’s not something that can be done in one, or even two terms of government. It’s a long-term project that will probably take decades. But overseas experience shows that it the thing that works, unlike education campaigns, which have never managed to create a mass cycling culture.

Evidence that riding bicycles (See table 1) comes from selected bicycle friendly EU countries which have the following 2010 road death rates per 100,000 population: – UK 2.9, Sweden 3.0, Netherlands 3.9, Japan 4.3, and Germany 4.7, Denmark 4.5, Switzerland 4.5 France 6.1. This is confirmed by the 2009 road death rates( in two the right hand side columns) and the child bicycle-pedestrians death rates for 0-14 year olds per 100,000 population. The Australian and US death rates in Table 1 are much higher. IRTAD does not publish Chinese data, but the 2007 death rate of 6.8 per 100,000 persons is known and better than the US (10.5 )and worse the EU countries in table 1.

In the Netherlands cyclists’ deaths have been reduce from 185 in 2009 to 162 in 2010. Since 1970 the reduction in road fatalities has benefited all age groups but the most impressive reduction has concerned young bicyclists ( age 0 to 14) for which fatalities decreased by 95%, from 459 in 1970 to 23 in 2008 (IRTAD 2011). 70% of Dutch urban roads have a 30 km/hr speed limit and the police take a tougher approach to unsafe drivers. The Netherlands has the fastest growing market for pedelecs with a 700,0000 fleet, mostly being used by the elderly.

Table 1 . Road deaths and death rates selected EU countries. Source IRTAD 2011

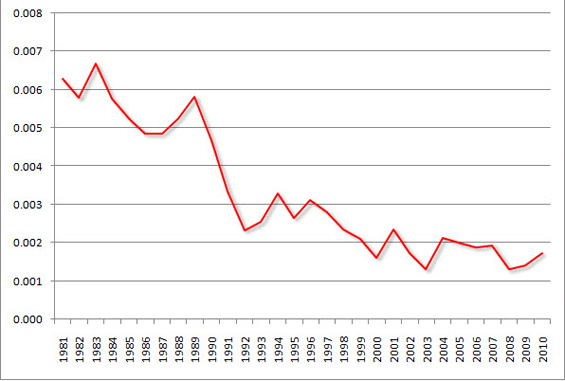

Dutch road deaths increased from 1950 (1,020) and peaked in 1972 (3,440) and then declined to 691 in 2010. The population grew from 10 to 16.5 million in 2010. In 2010 the traffic death rate was 3.7, deaths/100,000 population. Since 1970, the 95% reduction in child deaths (0 to 14) from 459 to 23 in 2008 was impressive. For the elderly of 65+ years deaths reduced from 648 in 1970 to 187 in 2009. (IRTAD 2011) The Dutch own 18 million bikes and about half of them ride around 2.5 km per day and used for around 25% all journeys and 35% of journeys below 7.5 km. Bicycles and pedelecs are safer because 70% of urban roads have 30 km/h speed limits or less in 2008. On rural roads in 1998 3% of the road length had a limit of 60 km/h, rising to 60% and much lower driving speeds by 2008.

One point I’ve wanted to make for a while is that while I don’t doubt there are significant parts of Melbourne that need better bicycling infrastructure, in the parts where it is already fairly decent it’s hard not to get the sense that it isn’t getting well used. And I think Alan and most commenters here are correct that it is largely down to the predominate culture of ‘roads are for cars’, or even just ‘cars are always the default mode of transport’. It does seem to me some of the biggest benefits would come from looking our kindergarten and primary school curricula to see if there isn’t room for a program to help get us get used to the idea that bicycles can have a far more important role in our lives than they do currently.

I would imagine that school curriculums already cover sustainable transport options, but the kids are more influenced by what mum and dad do, rather than what the teachers say. In any case, walking, public transport and cycling are still seen as “alternative” modes of transport – with all the negative connotations of the term (inconvenient, inefficient, inferior, for alternative types, for the smug).

Normalising bicycle use and other non-private car modes of getting around will come through the the influence of the market. At >$1.60 per litre of petrol, many people have less appetite for unnecessary car travel. Unfortunately, our governments will again intervene to prop us vehicle manufacturers, fuel sellers/distributers, and the “working families” with expensive cars to support; sacrificing proper levels of investment in infrastructure for PT, pedestrians and cyclists.

Hi Mark D,

Unfortunatly state and Commonwealth governments sacrificing proper levels of been investment in infrastructure for PT, pedestrians and cyclists has been a disaster that has not recognised here as it was in Japan In 1973.

Japan was always more dependent on imported fuels and the cost of electricity was very high with an ageing population. This explains the large Japanese investment in the rail network and the 27% of trips made to work or education by public transport by 1990. Seven million people cycle to the rail system every workday; around 15% of the population cycle all the way to work and another 12% walk to work. Japan’s energy security policy has reduced oil dependence in the transport sector from 80% in 1973 to a 55 % in 2010, thus reversing a negative trend.

Not only that but the Australian Bicycle Council (ABC) in its 2O11 report on the future of bicycling made no mention of the need for elderly and lame bicyclists of postal workers to use electric bicycles or the automatic version of the electric bicycles with no throttlle called a 250 watt pedelec that was invented in Japan and 400,000 where sold there but is illegal in Australia. Why ?

Fatih Birol, Chief Economist for the International Energy Agency (IEA), has warned that rising oil prices due to the conflicts in Libya and the Middle East could threaten the global economic

recovery now that oil production has peaked. On 30 May 2011 Birol said that energy related

2010 CO2 emissions were estimated to have climbed to a record 30.6 Gigatonnes (Gt). The

IEA has estimated that 80% of projected emissions from power stations in 2020 are already

locked in, as they are currently in place or under construction today. “This significant increase in CO2 emissions and the locking in of future emissions due to infrastructure investments represent a serious setback to our hopes of limiting global rise in temperature to no more than 2ºC.” The prospect of limiting the global temperature to 2% is getting bleaker and current rate of fuel consumption will push the global temperature up by 4°c. Perhaps a billion people will die as a consequence.

I believe in the bike revolution and that bike riding should be encouraged. I am not in favor of bikes and cars sharing the road. Why?

Cars pay for the roads and this money helps maintain them. The car might be poluting but the freedom it gives me has no comparision to anything else. I can be in many worlds in an hour. I can be in the country side or at the beach or at work or anywhere. I can travel there in comfort and safety.

Can you say the same for a bicycle?.

Is there a place for the bicycle? Yes. I want investment in only bicycle paths and road ways all around the city. I want a policy where a cyclist knows that they can find a bike path or road to minimise these kinds of problems associated with bikes and cars sharing the road.

I want maps of these like there own road network. I want the government buy up areas to create green wedges near the bike areas and put in infrastructure to make the city bike friendly. What kind of infrastructure? I want areas of shelter and places to store bikes. I want public amentities to make it work. I would go as far has being able to rent a shower after a bike ride. What ever it takes to make it work and convenient. What we want is to entise people out of the cars when its a nice sunny day and ride to work. They can know that there are facilities for them to come to work .

All this costs money. I think its well worth the investment. I have more to write but time stops me. bye.

The problem is that car ownership and use is so cheap and available that even people who don’t have the temperament, coordination and intelligence to be in charge of a potentially lethal vehicle can operate one. If driving was restricted to people competent to drive then bicycles and cars could safely share the roads and not have to use badly designed and unsafe bicycle paths.

Hi Johnyboy boy,

You have ignored many of the long term problems facing Melbourne’s cyclists.

A Melbourne bikeway arterial network is needed with a finer mesh than the main road network.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

The Vi crowds “principal bicycle network” in Melbourne is deficient and 12 years behind building it. Indeed, is also only 40% complete and not keeping up with urban growth. It will never complete at this rate, It also fails to create shortcuts to encourage bicycling and walking. What is needed is safe “arterial bicycle network “ to provide short cuts for cyclists and pedestrians which would encourage these modes. The residential street and local road network is very important because it connects with main road footpaths ‘ used by walkers, the disabled and by cyclists of all ages. More mid block crossings and refuges are needed to link up residential streets and create walking and cycling routes across main roads.

Most residential streets in the inner and middle suburbs are park of a grid iron pattern of streets so the provision of a safe arterial bicycle route network will require hundreds of safer main road crossings, with either signalised pedestrian crossings or centre of the road refuges to to link footpaths, residential streets, shared footways and back streets to bypass the congested main roads This residential street network could provide an alternative bikeway network would have 30 km speed limits as they have the Netherlands.

In many outer urban areas local street layouts a re a form of obsolete “cull de sac “planning without pedestrian and bicycle links at the closed off ends and walkers and cyclist do not have safe routes especially when the local roads do not have separate footpaths. The proposed “principal bicycle network” in Melbourne is deficient in the areas with these cull de sac street layouts because planners did not apply the English concept of the cul de sac by not providing the safe connecting links for children to have short cuts to other cul de sacs, parks, shops and schools.

An “arterial bikeway network” for the whole of Melbourne should provide safe routes over or under freeways, railway lines, rivers, some private property and other barriers that make it less convenient to walk and bicycle from A to B or wherever. This would complement main road bikelane along roads, linked with traffic calmed local streets and off-road shared footways, are required. Most one-way streets for cars should be two way for bicycles and roads with bike lanes and should have a maximum speed limit of 50 kph.

The introduction of a 50 kph limit on local roads in January 2002 in Victoria and the reduction of the legal leeway given to violators to 3 kph has local roads safer for cycling and walking. I t makes sense to have 30 Km/Hr residential bicycle routes to bypass sections of dangerous main roads. In the longer term a 40 km per limit on all residential streets is required as has been implemented in Unley in South Australia.. On outer urban residential streets without a footpath for child cyclists to use there should a 30 km per hour speed limit as there is in many European cities.

The mesh of the bikeway network would be 500m x 500m in the inner areas and 750m x 750m in the outer areas, or the rectangular equivalent of these sizes. In Melbourne a bicycle arterial network would be around 9,000 km long .The overall objective is too make Melbourne as safe as the fou r European countries whose road systems are safer for all road users than Australia .

Hi Michael ,

I agree “even people who don’t have the temperament, coordination and intelligence to be in charge of a potentially lethal vehicle can operate one.”Unfortuanely you have ignored many of the long term problems facing Melbourne’s cyclists. So I make my previous comment clearer .

My apologies to Johnyboy for the few typoes in my last comment.

A Melbourne bikeway arterial network is needed with a finer mesh than the main road network.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

The VicRoads “principal bicycle network” for Metropolitan Melbourne is deficient and 12 years behind construction. Indeed, it is only 40% complete and not keeping up with urban growth. It will never be complete at this rate. I t also fails to create shortcuts through road network to the encourage bicycling and walking. What is needed is safe “arterial bicycle network “ to provide short cuts for cyclists and pedestrians through the residential street and local road network that connects with main road footpaths ‘ used by walkers, the disabled and by cyclists of all ages. More mid block crossings and refuges are needed to link up residential streets and create walking and cycling routes across main roads. VicRoads does not want to know about more safe crossings beteen the main road traffic lights. Nor the multi lane roundabouts known by the UK Bicycle Tourin Club as the “the last round up for cyclists”. With over a 100, 000 members they Know what they are taalking about

In the 1980s maps showing state residential streets routes where produced by the State Bicycle Advisory Committee and these worked well in the inner and middle suburbs because most of them where a grid iron pattern of streets . However, today traffic congestion on main roads and many collector roads has so increased that crossing them mid block is dangerous unless there are mid block signalized crossings or middle of the road refuges. No problem with signalised crossings periods they can be timed to Integrated with the Main road Intersections signals so as not too slow down the car traffic which already platooned on most main roads.

Today the reality is that, a safe “arterial bicycle route network” will require hundreds of safer main road mid block crossings, to link footpaths, residential streets, shared footways and back streets to bypass the congested main roads This residential street network could provide an alternative bikeway network would have 30 km speed limits as they have the Netherlands. The 6,000 kms of residential streets could be opened up to encourage walking and cycling to work and school. Why waste such a resource that cost billions to build.

In many outer urban areas local street layouts a re a form of obsolete “cull de sac “planning without pedestrian and bicycle links at the closed off ends and walkers and cyclist do not have safe routes especially when the local roads do not have separate footpaths. The proposed “principal bicycle network” in Melbourne is deficient in the areas with these cull de sac street layouts because planners did not stick the English concept of the “cul de sac“ and mostly left out the safe connecting links for children to have short cuts to other “cul de sacs”, thus making it easier to have safer routes to parks, shops and schools. I ndeed the devil is in the detail.

An “arterial bikeway network” for the whole of Melbourne should provide safe routes over or under freeways, railway lines, rivers, some private property and other barriers that make it less convenient to walk and bicycle from A to B or wherever. This would complement main road bikelane a long roads, linked with traffic calmed local streets and off-road shared footways, are required. Most one-way streets for cars should be two way for bicycles and roads with bike lanes and should have a maximum speed limit of 50 kph. The introduction of a 50 kph limit on local roads in January 2002 in Victoria and the reduction of the legal leeway given to violators to 3 kph has made local roads safer for cycling and walking.

I t makes sense to have 30 Km/Hr residential speed limits mapped bicycle and walking routes to byepass sections of dangerous main roads as is done the Netherlands .A 40 km per limit on all residential streets is required as has been implemented in Unley in South Australia. On outer urban residential streets without a footpath for child cyclists to use there should a 30 km per hour speed limit as there is in many European cities.

The mesh of the bikeway network would be 500m x 500m in the inner areas and 750m x 750m in the outer areas, or the rectangular equivalent of these sizes. In Melbourne a bicycle arterial network would be around 9,000 km long .The overall objective is too make Melbourne as safe as the four European countries whose road systems which are safer for all road users than in Austrailia.

I like the idea of a good bike network. I just doubt it will be available within the next 50 years. The main problem is money, but the same kind of mentality that drivers have is also to found in planners and road engineers – that bikes are unsafe and discretionary, and anyone who rides them is both irresponsible for putting themselves in danger and indulgent, only riding for pleasure. Cycling is not taken seriously as a means of transport. That is why when they do make a piece of cycling infrastructure they build in dangerous curves, slippery surfaces, blind corners and routes that start and finish without connections. They also typically aren’t built as a response to route planning or surveys of bike usage. The only times I have come off my bike have been on badly designed bike tracks. So your hopes are completely unrealistic in this environment. I would be in favour of driver education, making driving more expensive and reduced speed limits. This could be quickly and cheaply implemented and would get more people cycling which would make drivers more used to seeing bikes. Forget about trying to build a bicycle network, because if it did get built it would be more of the same incompetence we suffer now.

Michael, you make quite a few points in your reply that i’d like to respond to:

~ planners and road engineers are acutely aware that bike riders need to be accomodated, but the general population (and their politicians) aren’t all on board yet;

~ poor cycling infrastructure, especially that found in open space is designed for shared use and many constrained sites along waterways are not suitable for fast riding. Some bike riders assume that park paths are bicycle super-highways – stupid, thoughtless and dangerous;

~ on-road bike lanes are often squeezed onto roads that can’t properly accomodate them – this is probably almost always a compromise to the amount available to spend (fact of life, perhaps);

~ walking, riding, catching PT and driving are all dangerous if one doesn’t take care – obviously, you can’t help it if a fuckwit in a car cleans you up, but

~ as fuel prices increase, there will be fewer priavte cars, more bikes, more pedestrians and more on PT, all contributing to making roads safer and meaning less need for bicycle networks.

safe riding!

The main problem can’t be money, because any realistic assessment of what Copenhagen have done in the last 30 years clearly shows they’ve saved massive amount of money by getting people out of cars and onto bicycles, which are much less expensive to provide infrastructure for.

hi wizofaus,

at no time in the last 30 years did any body at VicRoads make a rational assessment of what Copenhagen have done in the last 30 years which clearly shows they’ve saved massive amount of money by getting people out of cars and onto bicycles, which are much less expensive than providing infrastructure mostly for cars. To know the facts you need to go Copenhagen and find out or do as I did, go and visit 12 Dutch cities. The four bicycle Bicycle Friendly in Europe are all good Examples of best bicycle infrastucture development.

I know because for 5 years I was the on the Victorian State bicycle Committee for 12 years, the research officer at Bicycle Victoria than then 2 years as president of BV. After that several years as Vice President of the Bicycle Federation of Australia. My efforts in these advocacy roles is my articles and conference papers on my website on my Website.

Website http://alanparker-pest.org/

[…] the key issues for Australian cyclists (as identified in this article — What is the key challenge for cycling policy? ) are: (a) changing motorists perception that roads are exclusively for their use and cyclists, […]

Nobody owns the roads, but several bureaucracies have a specific role is creating a “road safety support system” based on the 4 E’s, principles: that is engineering, education , enforcement and encouragement. THis should apply in a competent way in all Australian states. The reality is very different and anarchic which why the rights of access and safety needs of bicyclists and pedestrians keep falling through the cracks fall through the cracks in the “road safety support system”.

Furthermore the bureaucracy left hand does Know what the bureaucracy right hand is doing. In urban planning it is even more so bureaucracy and the elite in the private sector cannot see the wood for the trees. Many consultants are so blind looking at the molecular structure of the leaves they cannot even see the tree.

EU countries’ policies on road safety for their citizens have differed greatly in the past. Since 1990 remarkable progress has been made. In all countries fatality risk has been reduced by more than 40%. In 2010, the lowest fatality rates found in the United Kingdom 3.0, the Netherlands 3.7 and Sweden 3.0 deaths per 100.000 persons. (IRTAD 2011) Three types of death rates based on IRTAD data are given below in Table 2.

Ideally, it is desirable to analyse the three road safety risks measures used by the international IRTAD accident analysis to compare the safety levels in those countries experiencing a large growth in both bicycle and pedelec usage, as is done for other road vehicles. In 2010 Pedelecs and E-bike fatalities are counted in with bicycle fatalities.

In Amsterdam with only 735,000 population where 50% of them ride bikes, there are 400 km of completely separate cycle ways and only about 6 people die in bike-related accidents a year. In the Netherlands 700,000 E-bikes and pedelecs were in use in 2010 with yearly sales adding 100,000 or so to the fleet. Dutch road deaths increased from 1950 (1,020) and peaked in 1972 (3440) and then declined to 691 in 2010, and the population grew from 10 million to 16.5 million in 2010.

In 2010 the traffic death rate was 3.7, deaths/100,000 population. In 2009 deaths/per billion veh-km was 5.5 and deaths/10,000 motor vehicle 0.7. Since 1970, the reduction in child deaths (0 to 14) from 459 to 23 in 2008 was impressive, decreasing by 95%. For the elderly of 65+ years deaths reduced from 648 in 1970 to 187 in 2009 (IRTAD 2011)

[…] factor that bears on the level of cycling, but quite frankly I think it’s a sideshow. As I’ve argued before, my feeling is that even in the unlikely event helmets were made discretionary, the great bulk of […]

[…] bound to get problematic. In the absence of infrastructure dedicated exclusively to bicycles, they belong on the road, not in bus […]

[…] What is the key challenge for cycling policy? […]